by Nathan P. Gibson

Today we are releasing the first collections of the Bibliography of the Arabic Bible (https://biblia-arabica.com/bibl), a new open-access tool intended to make research on the Arabic Bible a lot easier. This is the tool each of us wishes we had years ago when we began our study of the topic (speaking at least for the Biblia Arabica team). It represents two years of collaborative labor among our team and several external researchers, and it is a natural outgrowth of the DFG-funded stage of the Biblia Arabica project. It is also an attempt to give others a headstart in this important field by preserving what we have learned while combing through the literature. Consider it our present to the wider community.

Let me first explain what the bibliography covers and what we are releasing today. Then I’ll explain how to use it and how you can contribute to it.

Download the Bibliography flyer here

Scope & Status

The bibliography aims to include all Arabic Bible prints and all secondary literature on Arabic versions of the Bible, regardless of language. Currently we have entries in Arabic, English, Hebrew, French, German, Italian, Latin, and (coming soon) Russian. Translations made by three different communities––Jewish, Christian, and Samaritan––as well as citations by Muslim authors are all within scope. For more about this, see the Introduction.

That said, what we are releasing today is the first 200 of about 1500 entries we have drafted. These published entries make up part or all of the following subject collections: Generalia (edited by Ronny Vollandt), Gospels (edited by Robert Turnbull and Vevian Zaki), Pauline Epistles (edited by Vevian Zaki), Qaraite Translations (edited by Ronny Vollandt and Michael Wechsler), and Quotations in Christian Arabic Writings (edited by Peter Tarras).[1]

Our plan is to upload new entries fortnightly, so stay tuned!

Why a Bibliography and How to Use It

Take as an example my situation three years ago when I first became affiliated with the Biblia Arabica team. I had been trained in Arabic and Syriac, and I had read a few things about Arabic Bible translations. While working on my dissertation, I had come across a juicy passage in which the ninth-century Muslim author al-Jāḥiẓ appears to quote a string of Bible passages from Jewish translations, the longest of which comes from the book of Isaiah. I thought it should be possible to peruse several editions of medieval Arabic versions of Isaiah to see if it had anything in common with these. Of course, there were fewer of these than I imagined, and they were difficult to find. I asked my more experienced colleagues on the team for help, and they recommended a few secondary sources and showed me the lists of manuscripts they had compiled over the course of their research so that I could refer to these in lieu of editions. In the end, I learned that it is not that easy to engage the field of Arabic Bible even when one has the requisite skills, because (1) many aspects of it still lack scholarly studies, but also because (2) the literature is difficult to navigate. My colleagues told me they had the same experience. That’s why we created the Bibliography.

If I were searching today for the literature I needed for my earlier project of comparing al-Jāḥiẓ’s citation to other Arabic versions of Isaiah, here’s how I would do it.

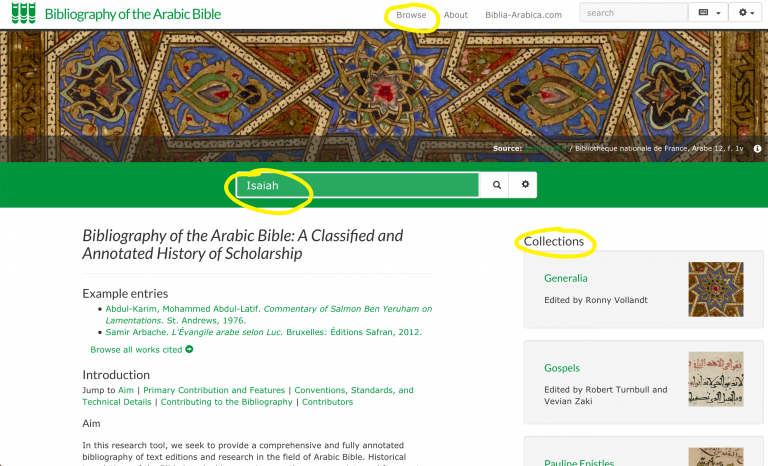

From the bibliography homepage, I would click on a relevant collection or enter a search for “Isaiah,” but my favorite place to go is “Browse.”[2]

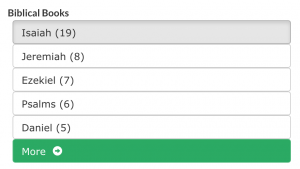

On the left, I see a list of ways to filter the bibliography, most of which are based on the way we have individually tagged each entry. To the extent possible, we have looked through each item to see, for example, which books of the Bible it relates to and which manuscripts it cites. This is one of the main values of the bibliography. I scroll past “Language,” “Biblical Parts” (Old Testament and New Testament) and “Biblical Sections” (Pauline Epistles, Prophets, etc.) to get to “Biblical Books,” where I can select “Isaiah.”

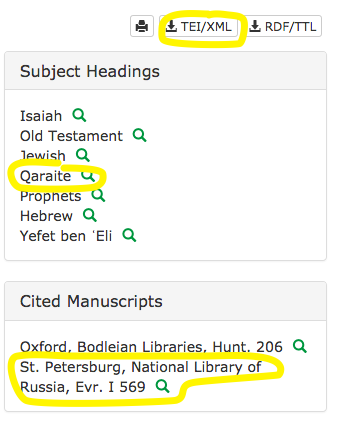

For now, there are a number of entries from the Jewish Qaraite Translations collection we have uploaded, as we can see from the list of translators, the source languages, and the communities of origin we have tagged.

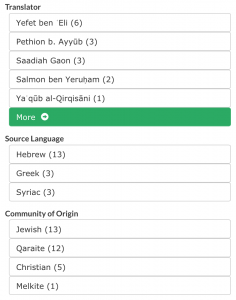

Just to emphasize the importance of the tags we have added, I should point out that if you look under the filter “Manuscript Shelfmark,” you will see that we have tagged about 100 different manuscripts for these entries relating to Isaiah. (This does not mean that all of these are manuscripts of Isaiah, only that these manuscripts are mentioned in the same articles that discuss Isaiah.) If I wanted to see all entries pertaining to both Isaiah and Ms. Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Hunt. 206, I could click on that particular manuscript. I could also clear the search for “Isaiah” and just see everything published on one particular manuscript.

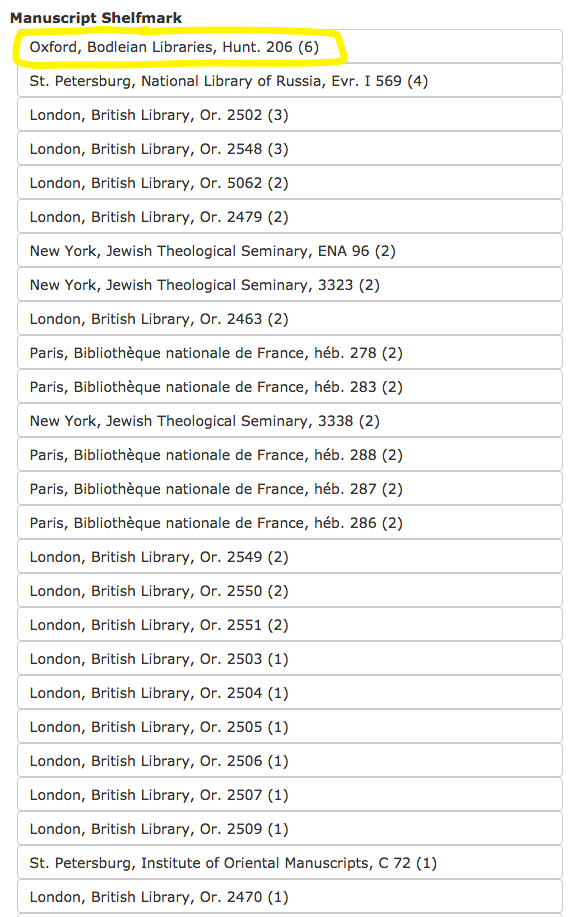

Once I click on a particular item, I can see the citation in Chicago style and copy the item’s URI (a digital identifier for the entry). I can also read a description of the item’s relevance for Arabic Bible written by the bibliography’s contributors. In many cases, I am just one click away from viewing an open-access version of the item.

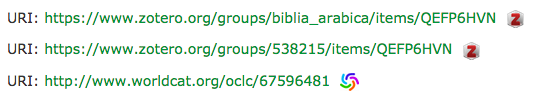

Under the list of URIs, I can find the item in the Biblia Arabica collection on Zotero.org or in WorldCat, and import it from there into Zotero or another bibliography manager.

Finally, I can see the subjects and manuscripts tagged for this entry and search by one of them. I can also download this entry as a data file in TEI-XML format, which I might want to do if I want to incorporate it into another digital project. All data in the bibliography is licensed under a CC-BY license, meaning it can be reused so long as its source is attributed (for example, by providing the item’s biblia-arabica.com URI).

How to Contribute

The Bibliography of the Arabic Bible is intended to be an open-ended tool that can constantly be updated and improved. Please let us know if you see information that is missing or incorrect. When you contact us, it would greatly help if you include the URI of the item that needs correction (for example, https://biblia-arabica.com/bibl/NWP4L3Q8).

If you’ve worked much in the field of Arabic Bible, you have probably collected a bibliography of your own. If you’re interested in this being included in our bibliography, please get in touch and let us know what the scope and format of your bibliography is.

And, lastly, be narcissistic! Look for your own publications in the bibliography. If they’re not there, let us know. There’s a good chance they are still in one of our draft collections waiting to be published, but we don’t want to miss out.

We’re excited to hear what you think of this brand-new resource!

Nathan P. Gibson is a Senior Research Associate with the Biblia Arabica project at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich.

Suggested Citation: Nathan P. Gibson, “Introducing the Bibliography of the Arabic Bible: An Annotated History of Scholarship”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 6 November 2018, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121637/.

Footnotes

[1] For more contributors, see the Introduction or the Flyer. Editor names are in alphabetical order.

[2] The web app (Srophé) used by the bibliography was created by Winona Salesky (developer). Data formats were developed by the Syriaca.org project.

Brenda Bickett

wonderful resource! Is based on the Catholic version or the Protestant version? My quick perusal of the all use info (which is very helpful) was not successful in this regard.

Many thanks for your assistance in this matter,

Brenda

Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies librarian, Georgetown University Library

Nathan Gibson

Thanks, Brenda! Actually we are including literature regarding all translations of the Bible into Arabic, regardless of who translated them. This includes not only Christian translations, but also Jewish and Samaritan. Among the Christian translations, you will find literature here on Catholic and Protestant printings in Arabic, but also on translations made during the medieval period by several other communities. These include Melkite (Arabic-speaking Byzantine Orthodox), Coptic, West Syriac (Syrian Orthodox), and East Syriac (Assyrian). Often it is difficult to know precisely which group was responsible for a translation, but we mark it as specifically as we can using the tag “Community of Origin”. You can filter by that on the Browse page.

We are still working on many of the entries for historic printings, which were often made by Catholics or Protestants using earlier manuscripts from other groups. So you should see more of these appear in the bibliography in the future.

Does that help?

Seth (Avi) Kadish

What a wonderful project! Thank you!

Will this also include biblical commentary in Arabic?

For instance: Saadia’s “translation” is really a consice commentary, but he also has a little ng commentary. And much translation will be found in commentaries, whether Jewish rabbinic, Qaraite, or Christian. Translation and commentary can only be separated artificially in the Middle Ages.

Nathan Gibson

Thanks, Seth!

Yes, we are definitely including commentaries. As you said, these are a vital source for medieval translations.