by Meira Polliack

Even amateur gardeners like myself recognize that plants don’t manage transitions easily. Some robust shrubs dry up in the best conditions of light or water. Yet, when transplanted in different soil, or in a discreet corner of the garden, they suddenly come alive, intensifying vigor and blossom. Shabby plants never fail to amaze me when upon such a swift move they release their green and lush potential, as if just waiting for their moment. Other, luxurious thickets, which grow in precarious conditions, and appear to be able to survive any transfer, wither the moment their roots touch an altered terrain, or when the wind brushes them in the wrong way, despite best attention. A sorry sight it is when they wilt in but a few hours. A careful gardener may even experience pangs of guilt over having disturbed them in the first place, thus tilting their exact balance of air, light and water. Similar heartbreak may be felt while engaging in the seemingly simple activity of clipping dry leaves and flowers. Without notice one can cut a delicate dry stem only to discover, alas, that looking more closely and more carefully, she would have seen a shy bud, just about to blossom, behind a parched leaf. So as not to commiserate with my readers any further: plants, like people, can misinform us about their ability to adapt and develop, or, may be misunderstood. To some extent and parallel, literary characters that endure in our memory or culture, are often those which, through some mysterious process, are able to make a successful transition from a certain text (or period) into a new context, or to somehow re-flower despite over or under trimmings of their character traits. Is this due to the creative imagination, narrative art and inexplicable power of discernment practiced by authors, editors and audiences? Or maybe, they manage these transitions due to the canonized or sanctified status of the texts, in which their story was preserved and continues to live on and prosper (such as the Hebrew Bible, New Testament or the Qur’ān)? Probably for these and other reasons, the afterlife of biblical characters is still at the core of our continuing fascination with Scripture.

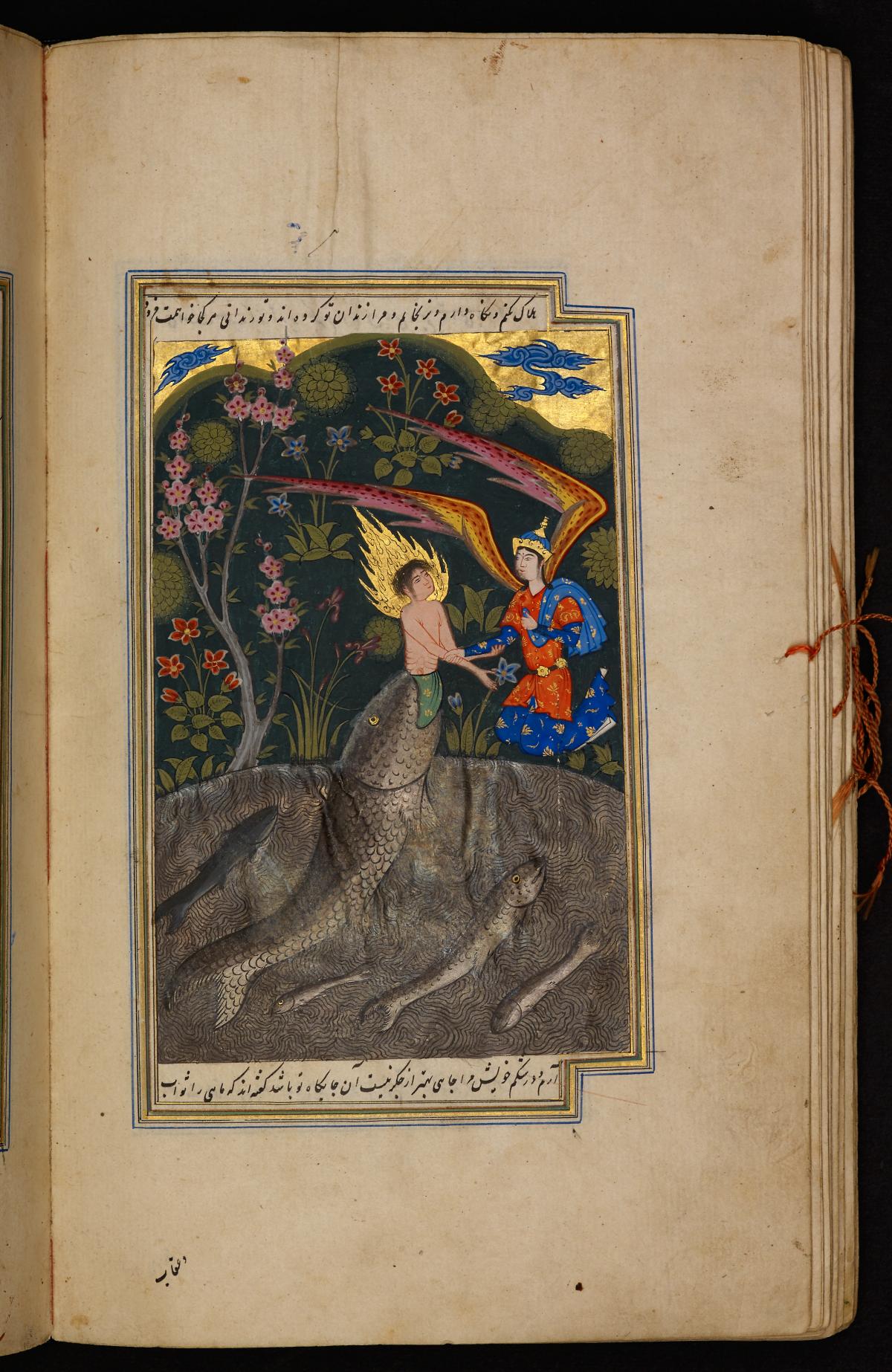

Isḥāq Ibn-Ibrāhīm Nīšāpūrī: Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, MS Diez a fol 3, f. 142v. The prophet Jonah, adorned with a halo, is spewed onto land by a large fish (see Jonah 2:1-2; 11). The angel Gabriel (Jibril) grasps Jonah’s arm to help him emerge from the fish and is about to give him new clothing. Source

No differently than the literary portraits of Ulysses, Hamlet or Lady Macbeth, those of the Bible’s major dramatis personae still engage readers, regardless of religious background or the question of their historicity. Amazingly, we are quite able to conjure some image of them in our mind’s eye the minute their name is mentioned, be it Abraham, Moses, David, Eve, Hannah or Mary, whether we hear their name in Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic, Latin, Arabic (or any other language).

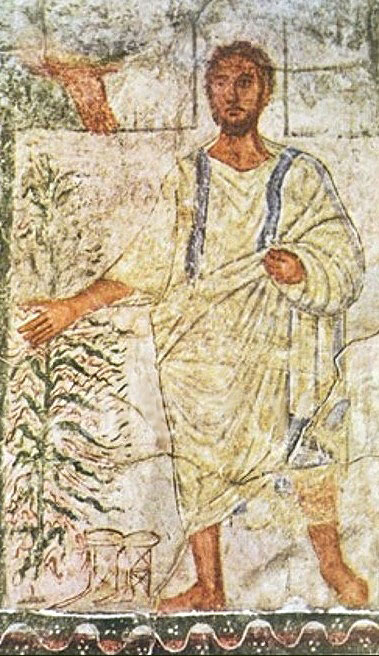

Dura Europos Synagogue, National Museum of Syria, Damascus. Moses, dressed in the himation (type of mantle) worn by a Hellenistic teacher. He stands barefoot, the shoes he was ordered to take off by his side (see Exodus 3:5), gesturing toward the burning bush. A hand appears above, referring to God or the angel of God who appeared in the bush (see Exodus 3:2). Source

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, MS Minutoli 291, f. 2vr. Mary and the child, with the three wise men bearing gifts and kneeling at the crib (see Matthew 2:1-12). Source

Like nature’s sturdy evergreens, such biblical characters are long-lasting perhaps because they have travelled a long and winding road not only through time, diachronically speaking, but also through geographical space, that is, a synchronic zone of interreligious, inter-linguistic and intercultural contact. Literary critics no doubt have deeper answers for why one literary type survives and another fades or disappears.[1] In the Biblia Arabica research group, and the wider consortium of scholars engaged in mapping out and understanding the medieval and early modern enterprise of rendering the Bible into Arabic, the question of character transformation (and its background) is “fraught with possibility.”[2] We can ask this question from an interreligious perspective, for instance, when we try and trace the translation practices that specifically relate to biblical characterization. One of these practices is identifiable in the “Muslim cast”[3] given to a biblical character, beyond the mere Arabization of the name.[4] The transformation from Joseph to Yūsuf, for example, far exceeds the Arabization of this character’s name. His subtle and successful “transplantation/adaption” in Islamic soil, depends on so many fine-tunings of light and shade, which invent him anew, and on earlier renditions of his “persona” in ancient Jewish and Christian sources.[5] In this lengthy process, the Arabic Bible versions also played their role in ways that need to be further explored in systematic studies of semantic and other forms of interpretive translation. Some biblical characters, like David (Da’ūd) or Job (Ayyūb), seem to travel nonchalantly, and perhaps with less interpretive baggage than Joseph (and others), in that they seem to retain an unswerving or elementary aspect of their biblical personality portrayal.[6]

Isḥāq Ibn-Ibrāhīm Nīšāpūrī: Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, MS Diez a fol 3, f. 82v. Joseph, on the left, and Jacob, on the right, embrace, their halos united. On the left, three of the brothers stand with Joseph’s horse and on the right, three brothers are with the camel sent by Joseph to Jacob. Above, the other five brothers observe. Source

When studying a range of subtle interreligious transitions, we are often preoccupied by questions relating to the scriptural meta-text, such as: In what ways do the translators deviate from the biblical source text (whether in Hebrew, Syriac or Greek), semantically, syntactically, stylistically, and otherwise in order to allow for subtle character transformations? Do certain personality or physical traits such as deviousness, righteousness, shrewdness, beauty, power, capacity for suffering, compassion etc., transform or undergo some form of change in the translated text, and if so, how? Is there a difference between Christian, Jewish, Samaritan and other subtypes when it comes to this type of rendering?

The renowned German-Jewish philosopher and cultural theorist, Walter Benjamin (1892 -1940), recognized translation as a creative process and was the first to draw attention to its wider cultural implications. In his famous essay “The Task of the Translator” (1923), he describes this process as largely independent from the original work itself, as follows:

“Just as the manifestations of life are intimately connected with the phenomenon of life without being of importance to it, a translation issues from the original – not so much from its life as from its after-life. For a translation comes later than the original, and since the important works of world literature never find their chosen translators at the time of their origin, their translation marks their stage of continued life”.[7]

Benjamin’s notion that the continued life of a literary work is dependent upon its successful “translatability” inspires and resonates in our study of the Arabic Bible versions. In similar vein, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s beautiful definition of translation as “the most intimate act of reading”[8] charts out the complexity of the medieval translators’ task, especially when it comes to Scripture. In this light we wonder how do the different translators “read” biblical characters, in context or outside of context? When Christian or Jewish Arabic versions use Arabized name forms of biblical characters, as in Mūsa for Moses, Ibrāhim for Abraham, and the like, we may not think of this as such a significant transition or transformation. After all, we say, “What’s in a name?” Yet often, the name rendering is but the inaugural step into after-life, or, in the humble horticultural metaphor with which I began, a live moment of “transplantation”, one in which a biblical character may thrive or wilt, may expand or shrink, depending on the force of her or his initial streaks and stamina, as well as the care taken by the “gardener” (our Jewish, or Christian translator, or our Muslim adaptor) to enable its roots to resettle in new soil. It is also the moment of successful “trimming” in as much as the character’s original traits are shaped and styled for the needs of a new audience.

The study of biblical character portrayals in Arabic translation or adaptation and its cross-cultural implications, is a fascinating field in which some of the Biblia Arabica researchers have been directly or indirectly engaged in recent years. Sivan Nir’s PhD Thesis (Tel Aviv University, 2019), “The Development of the Literary Character from Late Midrash Literature to Medieval Exegesis, as exemplified in the Characters of Balaam, Jeremiah and Esther” has broken new ground in showing, among other issues, how Jewish exegetes from Islamic lands favored certain types of characterization techniques, emphasizing the paradigmatic nature of religious figures, whilst those from Christian zones were inspired by the more biographic-typed characterization inherent to late Midrashim and by Christian study of rhetoric. Iqbal Abdel Raziq’s PhD Thesis (Tel Aviv University, 2020), “Divine Revelation to the Israelite Prophets according to Early and Classical Islamic Sources”, examines early Islamic notions of revelation to the Israelite prophets, based on the Qur’ān and the exegetical and theological compilations of central medieval Muslim scholars. Abdel Raziq offers illuminating discussions of ambivalent or unidentified figures mentioned in the Qur’ān, who are perceived as offspring of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Marzena Zawanovska has edited a fascinating new volume, entitled: Warrior, Poet, Prophet and King: The Character of David in Judaism, Christianity and Islam (forthcoming), which contains several comparative discussions of interreligious adaptations of David. The recent volume edited by Meira Polliack and Athalya Brenner-Idan, entitled Jewish Biblical Exegesis From Islamic Lands: The Medieval Period (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2019) also contains various articles bearing on biblical character renditions in translation and exegesis. In one of these, Zafer Tayseer Mohammad discusses “Saadia Gaon’s Translation of the References to Jerusalem in Isaiah 1-2: A Case Study in Lexical Choices” (see pp. 193-213), in which he concludes: “his (Saadia’s) translation succeeds not only in retaining the emotive aspects of the biblical text about Jerusalem but in enriching it, augmenting the enduring presence of Jerusalem by using a nonbiblical language – Arabic, the sacred language of the Qur’an.” Camilla Adang and Sabine Schmidtke have recently published Muslim Perceptions and Receptions of the Bible: Texts and Studies (Atlanta: Lockwood Press, 2019), in which they brought together their many articles dealing with Muslim perceptions and uses of the Bible in its wider sense. Finally, Arik Sadan has published a masterful edition, The Arabic Translation and Commentary of Yefet ben ʿEli the Karaite on the Book of Job (Leiden: Brill, 2020) which provides a hermeneutic milestone for the study of the afterlife of a biblical character within the medieval Islamic milieu in a cross-religious sense. In this voluminous commentary, the Karaite exegete, who lived in Jerusalem during the second half of the 10th century, offers his innovative theological and poetic explanations for the understanding of Job and his unjust sufferings as a universal character, a non-Israelite, who embodies the ideal of the believer in monotheistic faith. Yefet’s Arabic work on Job provides many links to the characterization of Job and the “growth” of his character not only in Jewish but also in Christian and Islamic medieval sources, which await further analysis and study.

These are but a few recent works which I have rather casually hand-picked for mention in this essay, while being well aware of the rich harvest which extends beyond its word limit, kindly afforded me by the editors, already, alas, outstretched by far (yet please see further works discussed on our website). All delve, among other issues, into the transformation of biblical characters in their journey between the Hebrew Bible, New Testament and Qur’ān, and these Scriptures’ subsequent interpretive traditions. Their research traces the fascinating process behind the arabicization of these characters, as one far more intricate than what meets the eye. The process may begin with an insignificant “once named” or “one verse” biblical character type, such as Enoch, whose presence in the Hebrew Bible is so elusive, and become a full-blown, layered character not only in Second Temple literature, but also one that is planted in the far-removed post biblical soil of the Arabic translation materials. Or, this process may involve a marginal and rather unassuming biblical character, who may be given a name in Arabic altogether lacking in the Hebrew (such as Zulaika, Potiphar’s wife), and ends up an altogether new and significant character, or, merges with another “rounder” biblical character. Finally, there are characters who like the cedars of the Lebanon, continue holding onto the same identifiable name (Avraham/Ibrahim; Moshe/Musa) and lofty position, their roots so heavy and thick in the soil of biblical consciousness that their immense canopies and powerful branches glide in some way into the inter-text and its afterlife. They retain their magnificence and splendor, in whatever language or context, despite being extracted or moved.

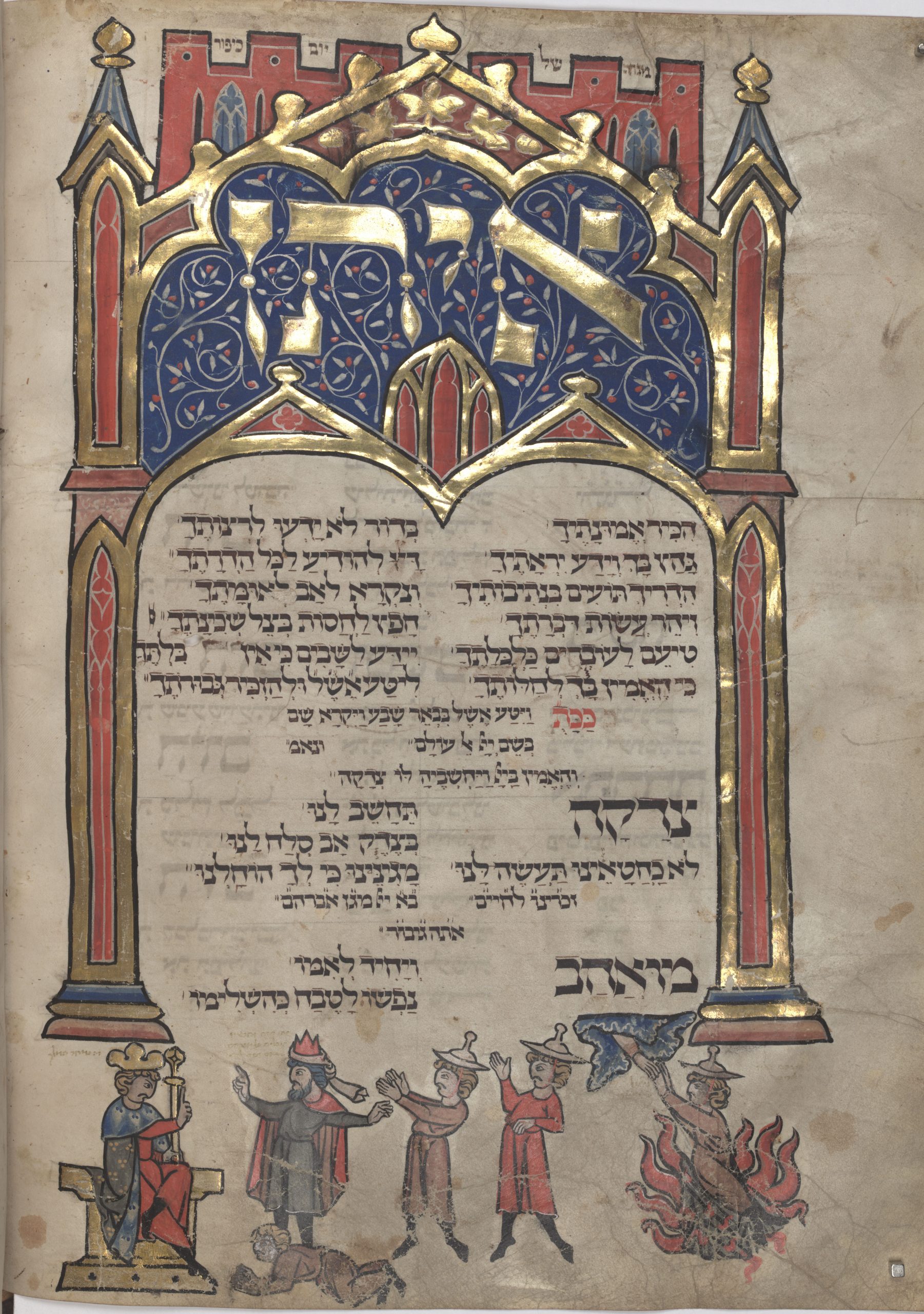

Leipzig Mahzor (MS Vollers 1102/II, f. 164). Nimrod sits on his throne, while Terah stands before him (attired in a crown-like head covering and a cape). His sons, Abraham and Nahor stand behind their father (both wearing medieval Jewish attire). The scorched figure of Haran lies at Terah’s feet, while to the far right Abraham is depicted as left unsinged by the flames and saved by God’s hand (cf. the midrash on the burning furnace, Genesis Rabbah 38:11). Source

Tripartite Mahzor, MS British Library, Add. 22413, vol. 2, fol. 3r. Moses standing on Mount Sinai receives the tables of the Covenant, inscribed with the Ten Commandments. Behind Moses, at the foot of the mountain, Aaron is depicted in priestly robes. Behind Aaron stand two separate groups: one of men wearing Jews` hats, and one of women, with animal faces. Above, trumpets/shofars burst out of the sky facing Moses. Source

An after-thought for an ending:

Despite the many political, technological and scientific transitions our civilization has undergone since the time in which the Jewish, Christian and Muslim scriptures were consolidated, we readers are still besotted by biblical characters. They engage us as literary figures regardless of religious belief or lack of it, whether due to psychological depths of identification they arouse in us, their imaginative or artistic valor, or as forms of cultural modelling. In the sorrowing current international arena and political atmosphere, in which so many physical borders are being closed, and levels of intercultural suspicion are at a disturbing rise, it might be good to remember, and take temporary solace in the thought that one can travel without airports and suitcases, into world literature, where Scripture is still an open and thriving international zone, one in which human contact is still much alive and continuously enacted through characters, and their joint legacy, in translation.

Meira Polliack is Professor of Bible and the Joseph and Ceil Mazer Chair in Jewish Culture in Muslim Lands and Cairo Geniza Studies at Tel Aviv University. She was one of the Principal Investigators of the DFG funded international research project (2012-2017): Biblia Arabica – The Bible in Arabic among Jews, Christians and Muslims. She has published extensively on medieval Judeo-Arabic Bible translation and biblical exegesis among the Jews of the Islamic world; modern and medieval literary approaches to the Hebrew Bible; historical development of biblical hermeneutics and notions of biblical narrative.

Suggested Citation: Meira Polliack, “Travelling in Translation with Biblical Characters”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 14 July 2020, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121823/.

Footnotes[1] See, for instance, Martin Puchner, The Written World, The Power of Stories to Shape People, History Civilization, New York: Random House, 2017, especially pages 46-61, 145-170, which discuss the Bible and its printing history’s effect on world literature.

[2] This phrase was coined by the literary critic Erich Auerbach, in his famous work Mimesis: Dargestellte Wirklichkeit in der abendländischen Literatur ( = Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. Willard R. Trask, Princeton, 1953 (repr. 1974)). In chapter one, entitled “Odysseus’ Scar”, Aurbach describes the artistic qualities of Hebrew biblical narrative, especially its paucity of detail, in comparing between the Odyssey and the story of the sacrifice of Isaac: “I said above that the Homeric style was “of the foreground”…. How fraught with background, in comparison, are characters like Saul and David” (see pages 7-8 therein).

[3] The effect of the Qur’ān and Islamic literature on the vocabulary and phraseology of the Christian Arabic versions of Scripture, as well as on other Christian Arabic works was aptly described by Richard M. Frank as the “Muslim cast” of the Arabic language of these texts, see his “The Jeremias of Pethion ibn Ayyūb al-Sahhār,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 21 (1959) 136-170 (esp. pp. 139-140). Cf. the illuminating discussion of Frank’s term in Sidney H. Griffith, “Syriac into Arabic: A New Chapter in the History of Syriac Christianity”, Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 16 (2016), 3-28 Qur’ān (esp. p. 6). Griffith too coined potent expressions of this process in referring to “the rubrics of Scriptural recall” in the Qur’ān, and the “the horizon of Biblical recall” in the Qur’ān (both wider and nearer), as well as “Scriptural recollection” by way of capturing its intricate “interface” with biblical themes, terms and dramatis personae. See what has become the standard work in the field, The Bible in Arabic: The Scriptures of the ‘People of the Book ’ in the Language of Islam (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013), 57-64. Also cf. Gabriel Said Reynold’s recent commentary on the Qur’ān (The Qur’ān and the Bible, Text and Commentary, Qur’ān Translation by Ali Quli Qarai, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018), in which parallel biblical (Hebrew Bible/Old Testament and New Testament) and para-biblical traditions are juxtaposed to the discussion of the verses, including of course, passages relating to the dramatis personae, in a useful and illuminating manner. For an important and innovative new French commentary (and wider study) on the Qur’ān, which attempts a thorough historical engagement with its Jewish and Christian inter-text, see, Ali Amir-Moezzi and Guillaume Dye (eds.), Le Coran des Historiens (Paris: Les éditions du Cerf, 2019; 3 vols).

[4] On the phenomenon of Arabized biblical names see Yosef Tobi: “Translations of Personal Names in Medieval Judeo-Arabic Bible Translations” [Hebrew], A. Demsky (ed.), These are the Names – Studies in Jewish Onomastics, vol. III, Ramat-Gan, Bar-Ilan University Press, 2002, 77-84. Tobi suggests that certain translation lexemes such as Arabic imām for Hebrew kohen, or Arabic qur’ān for Hebrew mikra and various personal Arabized biblical names were first coined in Jewish sources, including early (pre-Islamic) Judeo-Arabic Bible translations (and other, especially poetic, texts), from which they found their way to Arabic literature and eventually to Islamic Scripture. Tobi has held this view consistently throughout his prolific writings, see, for instance, Yosef Yuval Tobi, “Jewish Connections and Connotations in the Poetry of Imru’ al-Qays (ca. 497-545 CE)”, N. Masarwah, J. Sadan & Gh. Anabseh (eds.), In The Inkwell of Words: Studies in Arab Literature and Culture, In Honour of Professor Albert Arazi, Vol. II, Noor Publishing, 2017, 195–390.

[5] For a fascinating exploration of the cultural and literary ‘afterlife’ of this character see Mieke Bal, Loving Yusuf, Conceptual Travels from Present to Past, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008. For further engaging discussions of the wider implications of character renditions see Robert Wisnovsky, Faith Wallis, Jamie C. Fumo and Carlos Fraenkel (eds.), Vehicles of Transmission, Translation, and Transformation in Medieval Textual Culture (Cursor Mundi, 4; Turnhout: Brepols, 2011). Cf. Review by Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, Medieval Encounters 19 (2013), 586-595. Also cf. Sofía Torallas Tovar and Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala (eds.), Cultures in Contact

Transfer of Knowledge in the Mediterranean Context, Selected Papers (Spain: Oriens Academic, 2013).

[6] For a comparative discussion of aspects of the characterization of David and Bathsheba see Diana Lipton and Meira Polliack, “Our Mother, Our Queen: Bathsheba through Early Jewish, Christian and Muslim Eyes” in Marzena Zawanowska and Mateusz Wilk (eds.), Warrior, Poet, Prophet and King: The Character of David in Judaism, Christianity and Islam (and other relevant articles therein, forthcoming, 2021); In the recent Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception, edited by: Constance M. Furey, Brian Matz, Steven L. McKenzie, Thomas Chr. Römer, Jens Schröter, Barry Dov Walfish and Eric Ziolkowski (published in alphabetical volumes since 2009; Boston/Berlin: De Gruyter), one can find much information on Hebrew Bible/Old Testament and New Testament characters, spanning their reception exegesis in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and other religions as well as in literature, visual arts, music, and film.

[7] See Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator, An Introduction to the Translation of Baudelaire’s Tableaux parisiens” in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, Essays and Reflections, edited with an introduction by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 71.

[8] See Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “The Politics of Translation.” The Translation Studies Reader. Ed. Lawrence Venuti. London: Routledge, 2000, 398.

Helen Leneman

Thank you for this article! It is one of the most wonderfully written and fascinating I have read on the subject of biblical characters’ afterlives. My specialty (on which I’ve published 6 books) is the retelling of biblical narratives in musical settings, and some of your ideas and metaphors have truly inspired me. I expect I will be citing you in my next book!

Dr. Helen Leneman

Bethesda, MD

(I did my PhD with Athalya Brenner in Amsterdam; I’m sure you know her).