by David R. Vishanoff

The history of the Bible in Arabic

includes not only the reception of its textual content, and the reworking of

its stories and themes in various forms of “rewritten Bible,” but also the

reimagining of the Bible as a concept—in the minds of Muslims as well as Jews

and Christians. One particularly curious example of rewritten Bible is an

Arabic text purporting to be the “Psalms of David,” written by a Muslim to fit

a Qur’anic conception of the Zabūr. Rather than human prayers and

praises addressed to God, this collection of one hundred “suras” takes the form

of a divine revelation spoken by God to the prophet David, full of pious

admonitions about the enticements of this world and the terrors of the next.

“King David Playing the Harp.” Miniature pasted on an album leaf from the period of Shah Jahan. India, Mughal; 1610-1620 (miniature) and c. 1640 (leaf). The David Collection, Copenhagen, Inv. no. 31/2001. Here is a sample:

Blessed are the anxious, those stricken with fear, who comfort orphans with food and nourishment. Blessed are those who withdraw in silence from society and its vices, whose souls are afforded the most sublime insight. Blessed are those who rise to spend the night in vigil. But woe to those who go looking for adultery! The least that I will do to adulterers is to blot out the glow of health from their faces and wipe away both their lifespan and their livelihood. Blessed are those who think too highly of me to gaze on the private parts of those forbidden to them, fearing my punishment.[1]

This new scripture’s form and content

suggest that it was intended as a collection of sermon material, while its

fearful and ascetical tone suggest that its author was one of the khāʾifūn

and zuhhād who, modeling themselves partly on Christian monks, upheld for

a century or two an ascetic strand of Muslim piety that was displaced in the

ninth century by mystical and legal forms of piety.[2] The

recent discovery by Ursula Bsees of two papyrus leaves containing psalms 7–13

shows that the original Core text does indeed date back to the eighth or early

ninth century.[3]

In subsequent centuries it was frequently copied, edited, expanded, rearranged,

and even radically rewritten, resulting in a dozen different recensions.[4]

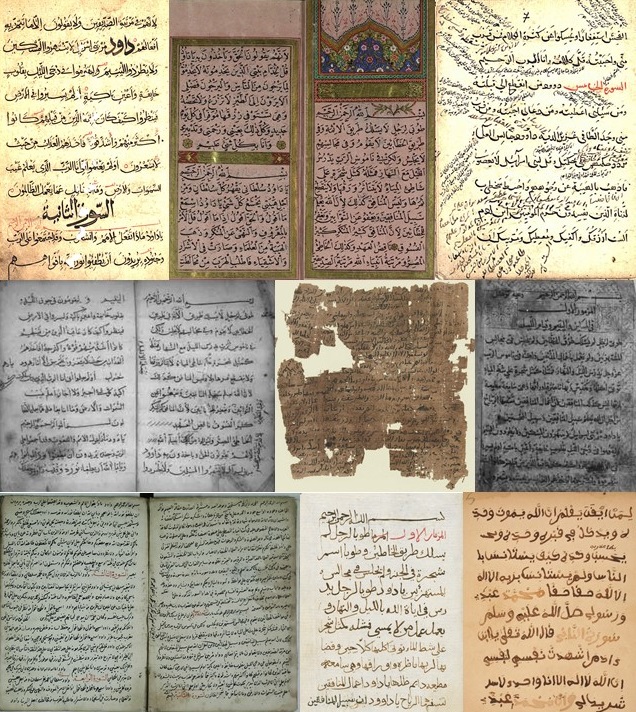

Recensions and selected manuscripts of the Islamic Psalms. These psalms appear to be original

compositions, but their authors drew on, alluded to, or were inspired by

several kinds of material: short passages from the Biblical Psalms and Gospels,

ḥadīth qudsī, qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, ḥikma, zuhd, the Qur’an, and possibly

some “Sayings of the Desert Fathers.” The author of the Core text did not have direct

access to the Biblical Psalms, but employed paraphrases of a few famous

passages that had been learned orally and were circulating among Muslims. Even

the later editors do not appear to have used Arabic translations of the Bible,

with one exception: the editor of the Sufi recension used an Arabic

translation, made from Hebrew, of Psalms 1–3.[5]

Although only a fragment of the Core text

survives, its contents can often be reconstructed from the later recensions,

each of which expanded and modified it in keeping with its editor’s own

inclinations. For example, the “Sufi” editor elaborated on themes such as

divine love, the “Pious” editor replaced love with obedience, and the

“Orthodox” editor rectified theological problems such as allusions to David’s sin

of adultery—a Biblical story that was known among early Muslims but was quickly

modified or suppressed as unworthy of a prophet.[6]

Some manuscripts of the Islamic Psalms. Copies of these recensions circulated

from Iran and the Caucasus in the East to al-Andalus and Timbuktu in the West. (The

“Broken Pious with Moses” recension was especially popular in Jerusalem.) Some

copies were included in collections of sermons or alongside treatises on

scrupulous piety (waraʿ ), while others were made to look like copies of

the Qur’an, with sura headings, verse divisions, and recitation marks. Dozens

and probably hundreds of copies were produced between the 13th and 18th

centuries, but interest faded as Arabic translations of the Christian Bible became

widely available in print. A handful of scholarly articles drew attention to

them in the early 20th century,[7] but

since that time they have been almost entirely forgotten by Western as well as Muslim

scholars. The only version to have been printed[8] is a small

collection that was originally associated with Moses before being recast as

Psalms of David; it is still being used in West Africa today for the training

of preachers in Qur’anic schools.[9]

Since

I have found no complete copy of the Core text, I am preparing a critical

edition and English translation of the Koranic recension, which does not

diverge much from the Core text. I believe these rewritten psalms are worth

bringing back into view, not because of their implicit polemical claim to be

more authentic than the corrupted Biblical Psalms—a pretension belied by the

Muslim editors’ eagerness to improve the text at every opportunity—but because

of their historical value for the early history of Muslim piety, and also for

what they reveal about the function of the Bible in the Islamic milieu. The

Bible is not just a text; it is a repertoire of narratives, characters, concepts,

values, and symbols that Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike can reinterpret

and redeploy for their own purposes. The Bible is also a concept, an imagined

idea that changes shape as it moves into new linguistic and religious environments.

That is why the “Psalms of David” could be given a whole new text, and thus be

made to serve Muslim ascetics as well as Christian monks.

David Vishanoff is Associate Professor of Islamic studies in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Oklahoma, where he teaches courses on the Qur’an, Islamic theology, Islamic law, and comparative topics in religious studies. He received his Ph.D. in West and South Asian Religions from Emory University in 2004. His research is principally concerned with how religious people interpret and conceptualize sacred texts—both their own and those of other religious traditions. His publications have dealt with the early history of Islamic legal theory and hermeneutics, and with uses of scripture across religious lines, especially Muslim rewritings of the Psalms. He is presently editing and translating one version of the Islamic Psalms, and studying modern developments in Qur’anic hermeneutics beginning with recent developments in Indonesia, where he spent the spring of 2013 as a Fulbright scholar. This work has led him to dabble in digital methods of data visualization and “distant reading.”

Suggested Citation : David R. Vishanoff, “The “Psalms of David” as reimagined and rewritten by

Muslims”, Biblia Arabica Blog , 14 May 2019, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121807/ .

Footnotes

[1] Psalm 5.5 from the Koranic recension (corresponding to 4.5 of the

Core text) based on MS Istanbul, Süleymaniye, Fatih 28, fol. 4b.2–8, and MS Madrid,

National Library, MSS/5146, fols 208b.21–209a.4.

[2] See Hurvitz, “Biographies and Mild Asceticism;” Melchert, “Exaggerated

Fear in the Early Islamic Renunciant Tradition;” Melchert, “The Islamic

Literature on Encounters between Muslim Renunciants and Christian Monks;” Melchert, “The

Transition from Asceticism to Mysticism at the Middle of the Ninth Century

C.E.”

[3] MSS Vienna, Austrian National Library, A. P. 01854 a Pap and A. P.

01854 b Pap, of which Ursula Bsees and David Vishanoff are preparing an

edition.

[4] For an overview of several recensions see Vishanoff, “An Imagined

Book Gets a New Text.” I will give an updated and expanded overview in an

edition of the Koranic recension that I hope to complete this year.

[5] See Vishanoff, “Why Do the Nations Rage?” 153–158.

[6] See Déclais,

David raconté par les musulmans, 187–211.

[7] See the works of Cheikho, Krarup, Mukhliṣ, and Zwemer listed in

the bibliography.

[8] al-Mukhtār, ed., Mawāʿiẓ balīgha min Zabūr sayyidinā Dāwūd .

[9] Personal communication from Dr. Yushau Sodiq of Texas Christian

University, March 2019.

Bibliography

538215

{538215:2WJI6N6F},{538215:HYSC2S48},{538215:IIJB4V85},{538215:7ZSFCPKW},{538215:44XRTRYK},{538215:C6ZLKEXH},{538215:NJLGCQPC},{538215:8MC3H9A6},{538215:LDEVZFQ4},{538215:NX5IEJYR},{538215:6S7W2B27},{538215:LNRUXFJN},{538215:JG6WPLNC},{538215:4LA486PY},{538215:G2YLCCCT},{538215:SIRPCNZ8},{538215:QAQF4D54},{538215:ECRV9WYC},{538215:FN3AZHX9}

1

chicago-fullnote-bibliography

50

creator

asc

1

1

4573

https://biblia-arabica.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3Afalse%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%224LA486PY%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22al-Mukht%5Cu0101r%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221937%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMukht%26%23x101%3Br%2C%20Ya%26%23x2BF%3Bq%26%23x16B%3Bb%20al-%2C%20ed.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BMaw%26%23x101%3B%26%23x2BF%3Bi%26%23x1E93%3B%20bal%26%23x12B%3Bgha%20min%20Zab%26%23x16B%3Br%20sayyidin%26%23x101%3B%20D%26%23x101%3Bw%26%23x16B%3Bd%20%26%23x2BF%3Balayhi%20al-sal%26%23x101%3Bm%20wa-ghayrihi%20min%20al-kutub%20al-munazalla%20wa-jumlatuh%26%23x101%3B%20thal%26%23x101%3Bth%26%23x16B%3Bna%20s%26%23x16B%3Bratan%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B.%20Cairo%3A%20%26%23x645%3B%26%23x637%3B%26%23x628%3B%26%23x639%3B%26%23x629%3B%20%26%23x645%3B%26%23x635%3B%26%23x637%3B%26%23x641%3B%26%23x649%3B%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x628%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x628%3B%26%23x64A%3B%2C%201937.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3D4LA486PY%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Maw%5Cu0101%5Cu02bfi%5Cu1e93%20bal%5Cu012bgha%20min%20Zab%5Cu016br%20sayyidin%5Cu0101%20D%5Cu0101w%5Cu016bd%20%5Cu02bfalayhi%20al-sal%5Cu0101m%20wa-ghayrihi%20min%20al-kutub%20al-munazalla%20wa-jumlatuh%5Cu0101%20thal%5Cu0101th%5Cu016bna%20s%5Cu016bratan%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ya%5Cu02bfq%5Cu016bb%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22al-Mukht%5Cu0101r%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Reprinted%20from%20the%201936%20edition%20%7Bhttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fgroups%5C%2F538215%5C%2Fbiblia_arabica%5C%2Fitems%5C%2FitemKey%5C%2FJG6WPLNC%7D%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221937%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22al-mukhtarMawaizBalighaMin1937%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22ar%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22JG6WPLNC%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22al-Mukht%5Cu0101r%20and%20%5Cu0627%5Cu0644%5Cu0645%5Cu062e%5Cu062a%5Cu0627%5Cu0631%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221936%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMukht%26%23x101%3Br%2C%20Ya%26%23x2BF%3Bq%26%23x16B%3Bb%20al-%2C%20and%20%26%23x64A%3B%26%23x639%3B%26%23x642%3B%26%23x648%3B%26%23x628%3B%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x645%3B%26%23x62E%3B%26%23x62A%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x631%3B%2C%20eds.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3B%26%23x645%3B%26%23x648%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x639%3B%26%23x638%3B%20%26%23x628%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x64A%3B%26%23x63A%3B%26%23x629%3B%20%26%23x645%3B%26%23x646%3B%20%26%23x632%3B%26%23x628%3B%26%23x648%3B%26%23x631%3B%20%26%23x633%3B%26%23x64A%3B%26%23x62F%3B%26%23x646%3B%26%23x627%3B%20%26%23x62F%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x648%3B%26%23x62F%3B%20%26%23x639%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x64A%3B%26%23x647%3B%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x633%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x645%3B%20%26%23x648%3B%26%23x63A%3B%26%23x64A%3B%26%23x631%3B%26%23x647%3B%20%26%23x645%3B%26%23x646%3B%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x643%3B%26%23x62A%3B%26%23x628%3B%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x645%3B%26%23x646%3B%26%23x632%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x629%3B%20%7C%7C%20Sermons%20from%20the%20Psalms%20of%20David%20%28Peace%20be%20upon%20him%29%20and%20other%20Inspired%20Books%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B.%20Cairo%20%7C%7C%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x642%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x647%3B%26%23x631%3B%26%23x629%3B%3A%20%26%23x645%3B%26%23x635%3B%26%23x637%3B%26%23x641%3B%26%23x649%3B%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x628%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x628%3B%26%23x64A%3B%20%26%23x627%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x62D%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x628%3B%26%23x64A%3B%20%26%23x648%3B%26%23x623%3B%26%23x648%3B%26%23x644%3B%26%23x627%3B%26%23x62F%3B%26%23x647%3B%2C%201936.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DJG6WPLNC%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22%5Cu0645%5Cu0648%5Cu0627%5Cu0639%5Cu0638%20%5Cu0628%5Cu0644%5Cu064a%5Cu063a%5Cu0629%20%5Cu0645%5Cu0646%20%5Cu0632%5Cu0628%5Cu0648%5Cu0631%20%5Cu0633%5Cu064a%5Cu062f%5Cu0646%5Cu0627%20%5Cu062f%5Cu0627%5Cu0648%5Cu062f%20%5Cu0639%5Cu0644%5Cu064a%5Cu0647%20%5Cu0627%5Cu0644%5Cu0633%5Cu0644%5Cu0627%5Cu0645%20%5Cu0648%5Cu063a%5Cu064a%5Cu0631%5Cu0647%20%5Cu0645%5Cu0646%20%5Cu0627%5Cu0644%5Cu0643%5Cu062a%5Cu0628%20%5Cu0627%5Cu0644%5Cu0645%5Cu0646%5Cu0632%5Cu0644%5Cu0629%20%7C%7C%20Sermons%20from%20the%20Psalms%20of%20David%20%28Peace%20be%20upon%20him%29%20and%20other%20Inspired%20Books%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ya%5Cu02bfq%5Cu016bb%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22al-Mukht%5Cu0101r%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22%5Cu064a%5Cu0639%5Cu0642%5Cu0648%5Cu0628%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22%5Cu0627%5Cu0644%5Cu0645%5Cu062e%5Cu062a%5Cu0627%5Cu0631%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221936%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22al-mukhtarMwaaZBlyGMn1936%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22ar%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%222WJI6N6F%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Cheikho%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221910%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BCheikho%2C%20Louis.%20%26%23x201C%3BQuelques%20L%26%23xE9%3Bgendes%20Islamiques%20Apocryphes.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BM%26%23xE9%3Blanges%20de%20la%20Facult%26%23xE9%3B%20orientale%20Beyrouth%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%204%20%281910%29%3A%2033%26%23x2013%3B56.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3D2WJI6N6F%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Quelques%20L%5Cu00e9gendes%20Islamiques%20Apocryphes%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Louis%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Cheikho%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22On%20the%20influence%20of%20biblical%20and%20apocryphal%20material%20J%5Cu0101hil%5Cu012b%20poets%2C%20Qur%5Cu02be%5Cu0101n%2C%20and%5Cnearly%20Muslim%20authors.%20Contains%20references%20to%20Muslim%20Pseudo-Scriptures%20%28see%20below%29.%5Cn%5CnCook%2C%20David%2C%20%5Cu201cNew%20Testament%20Citations%20in%20the%20%5Cu1e24ad%5Cu012bth%20Literature%20and%20the%20Question%20of%20Early%20Gospel%20Translations%20into%20Arabic.%5Cu201d%20In%20Emmanouela%20Grypeou%2C%20Mark%20N.%20Swanson%2C%20and%20David%20Thomas%2C%20eds.%2C%20The%20Encounter%20of%20Eastern%20Christianity%20with%20Early%20Islam%20%28Leiden%2C%202006%29%2C%20pp.%20185-223.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221910%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22cheikhoQuelquesLegendesIslamiques1910%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22French%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22ZY49CXC6%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22HYSC2S48%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22D%5Cu00e9clais%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221999%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BD%26%23xE9%3Bclais%2C%20Jean-Louis.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BDavid%20racont%26%23xE9%3B%20par%20les%20musulmans%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B.%20Patrmoines%20Islam.%20Paris%3A%20Editions%20du%20Cerf%2C%201999.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DHYSC2S48%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22David%20racont%5Cu00e9%20par%20les%20musulmans%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Jean-Louis%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22D%5Cu00e9clais%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221999%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-2-204-06220-6%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22declaisDavidRacontePar1999%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22fr%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22IIJB4V85%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Hurvitz%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221997%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BHurvitz%2C%20Nimrod.%20%26%23x201C%3BBiographies%20and%20Mild%20Asceticism.%20A%20Study%20of%20Islamic%20Moral%20Imagination.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BStudia%20Islamica%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%20no.%2085%20%281997%29%3A%2041%26%23x2013%3B65.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DIIJB4V85%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Biographies%20and%20Mild%20Asceticism.%20A%20Study%20of%20Islamic%20Moral%20Imagination%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Nimrod%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hurvitz%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221997%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22hurvitzBiographiesMildAsceticism1997%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220585-5292%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%227ZSFCPKW%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Khoury%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221977%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BKhoury%2C%20Raif%20Georges.%20%26%23x201C%3BQuelques%20R%26%23xE9%3Bflexions%20sur%20les%20citations%20de%20la%20Bible%20dans%20les%20premi%26%23xE8%3Bres%20g%26%23xE9%3Bn%26%23xE9%3Brations%20islamique%20du%20et%20du%20deuxi%26%23xE8%3Bme%20si%26%23xE8%3Bcle%20de%20l%26%23x2019%3BH%26%23xE9%3Bgire.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BBulletin%20d%26%23x2019%3B%26%23xE9%3Btudes%20orientales%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2029%20%281977%29%3A%20269%26%23x2013%3B78.%20%26lt%3Ba%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-ItemURL%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.jstor.org.0011f5uj08a3.emedia1.bsb-muenchen.de%5C%2Fstable%5C%2Fpdf%5C%2F41604624.pdf%3Frefreqid%3Dsearch%3A0e25e21962886ec51d70f7a8d340b77c%26%23039%3B%26gt%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.jstor.org.0011f5uj08a3.emedia1.bsb-muenchen.de%5C%2Fstable%5C%2Fpdf%5C%2F41604624.pdf%3Frefreqid%3Dsearch%3A0e25e21962886ec51d70f7a8d340b77c%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3D7ZSFCPKW%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Quelques%20R%5Cu00e9flexions%20sur%20les%20citations%20de%20la%20Bible%20dans%20les%20premi%5Cu00e8res%20g%5Cu00e9n%5Cu00e9rations%20islamique%20du%20et%20du%20deuxi%5Cu00e8me%20si%5Cu00e8cle%20de%20l%27H%5Cu00e9gire%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Raif%20Georges%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Khoury%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22On%20Wahb%20b.%20Munabbih%2C%20Ka%5Cu02bfb%20al-A%5Cu1e25b%5Cu0101r%2C%20and%20xxx.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221977%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22khouryQuelquesReflexionsCitations1977%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.jstor.org.0011f5uj08a3.emedia1.bsb-muenchen.de%5C%2Fstable%5C%2Fpdf%5C%2F41604624.pdf%3Frefreqid%3Dsearch%3A0e25e21962886ec51d70f7a8d340b77c%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220253-1623%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22fr%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22ZY49CXC6%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%2244XRTRYK%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Khoury%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221972%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BKhoury%2C%20Raif%20Georges.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BWahb%20b.%20Munabbih.%20Teil%201%3A%20Der%20Heidelberger%20Papyrus%20PSR%20Heid%20Arab%2023.%20Leben%20und%20Werk%20des%20Dichters.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%20Vol.%201.%202%20vols.%20Wiesbaden%3A%20Otto%20Harrassowitz%2C%201972.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3D44XRTRYK%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Wahb%20b.%20Munabbih.%20Teil%201%3A%20Der%20Heidelberger%20Papyrus%20PSR%20Heid%20Arab%2023.%20Leben%20und%20Werk%20des%20Dichters.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Raif%20Georges%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Khoury%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221972%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-3-447-01469-4%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22khouryWahbMunabbihTeil1972%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22de%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22C6ZLKEXH%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Krarup%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221909%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BKrarup%2C%20Ove%20Chr.%2C%20ed.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BAuswahl%20Pseudo-Davidischer%20Psalmen%3A%20Arabisch%20und%20Deutsch.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%20Copenhagen%3A%20G.E.C.%20Gad%2C%201909.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DC6ZLKEXH%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Auswahl%20Pseudo-Davidischer%20Psalmen%3A%20Arabisch%20und%20Deutsch.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ove%20Chr.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Krarup%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221909%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22krarupAuswahlPseudoDavidischerPsalmen1909%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22de%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22NJLGCQPC%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Melchert%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222011%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMelchert%2C%20Christopher.%20%26%23x201C%3BExaggerated%20Fear%20in%20the%20Early%20Islamic%20Renunciant%20Tradition.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BJournal%20of%20the%20Royal%20Asiatic%20Society.%20Series%203%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2021%2C%20no.%203%20%282011%29%3A%20283%26%23x2013%3B300.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DNJLGCQPC%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Exaggerated%20Fear%20in%20the%20Early%20Islamic%20Renunciant%20Tradition%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Christopher%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Melchert%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222011%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22melchertExaggeratedFearEarly2011%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221356-1863%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22NX5IEJYR%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Melchert%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221996%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMelchert%2C%20Christopher.%20%26%23x201C%3BThe%20Transition%20from%20Asceticism%20to%20Mysticism%20at%20the%20Middle%20of%20the%20Ninth%20Century%20C.E.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BStudia%20Islamica%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%20no.%2083%20%281996%29%3A%2051%26%23x2013%3B70.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DNX5IEJYR%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Transition%20from%20Asceticism%20to%20Mysticism%20at%20the%20Middle%20of%20the%20Ninth%20Century%20C.E.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Christopher%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Melchert%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221996%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22melchertTransitionAsceticismMysticism1996%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220585-5292%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%228MC3H9A6%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Melchert%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222012%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMelchert%2C%20Christopher.%20%26%23x201C%3BThe%20Islamic%20Literature%20on%20Encounters%20between%20Muslim%20Renunciants%20and%20Christian%20Monks.%26%23x201D%3B%20In%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BMedieval%20Arabic%20Thought.%20Essays%20in%20Honour%20of%20Fritz%20Zimmermann%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%20edited%20by%20Rotraud%20Hansberger%2C%20M.%20Afifi%20al-Akiti%2C%20and%20Charles%20Burnett%2C%20135%26%23x2013%3B42.%20London%3A%20The%20Warburg%20Institute%2C%202012.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3D8MC3H9A6%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22bookSection%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Islamic%20Literature%20on%20Encounters%20between%20Muslim%20Renunciants%20and%20Christian%20Monks%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Christopher%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Melchert%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Rotraud%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hansberger%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22M.%20Afifi%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22al-Akiti%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Charles%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Burnett%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22bookTitle%22%3A%22Medieval%20Arabic%20Thought.%20Essays%20in%20Honour%20of%20Fritz%20Zimmermann%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222012%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-1-908590-71-8%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22melchertIslamicLiteratureEncounters2012%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22LDEVZFQ4%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Melchert%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222013%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMelchert%2C%20Christopher.%20%26%23x201C%3BQuotations%20of%20Extra-Qur%26%23x2019%3B%26%23x101%3Bnic%20Scripture%20in%20Early%20Renunciant%20Literature.%26%23x201D%3B%20In%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BIslam%20and%20Globalisation.%20Historical%20and%20Contemporary%20Perspectives.%20Proceedings%20of%20the%2025th%20Congress%20of%20l%26%23x2019%3BUnion%20Europ%26%23xE9%3Benne%20Des%20Arabisants%20et%20Islamisants%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%20edited%20by%20Agostino%20Cilardo%2C%2097%26%23x2013%3B107.%20Leuven%3A%20Peeters%2C%202013.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DLDEVZFQ4%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22bookSection%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Quotations%20of%20Extra-Qur%5Cu2019%5Cu0101nic%20Scripture%20in%20Early%20Renunciant%20Literature%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Christopher%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Melchert%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Agostino%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Cilardo%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22bookTitle%22%3A%22Islam%20and%20Globalisation.%20Historical%20and%20Contemporary%20Perspectives.%20Proceedings%20of%20the%2025th%20Congress%20of%20l%27Union%20europ%5Cu00e9enne%20des%20Arabisants%20et%20Islamisants%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222013%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-90-429-2941-8%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22melchertQuotationsExtraQurAnic2013%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%226S7W2B27%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Mukhli%5Cu1e63%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221932%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMukhli%26%23x1E63%3B%2C%20%26%23x2BF%3BAbd%20All%26%23x101%3Bh.%20%26%23x201C%3Bal-Zab%26%23x16B%3Br%20al-shar%26%23x12B%3Bf.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BMajallat%20al-Majma%26%23x2BF%3B%20al-%26%23x2BF%3BIlm%26%23x12B%3B%20al-%26%23x2BF%3BArab%26%23x12B%3B%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2012%20%281932%29%3A%20627%26%23x2013%3B30.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3D6S7W2B27%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22al-Zab%5Cu016br%20al-shar%5Cu012bf%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22%5Cu02bfAbd%20All%5Cu0101h%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Mukhli%5Cu1e63%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221932%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22mukhlisAlZaburAlsharif1932%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22ar%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22LNRUXFJN%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Mukhli%5Cu1e63%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221933%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BMukhli%26%23x1E63%3B%2C%20%26%23x2BF%3BAbd%20All%26%23x101%3Bh.%20%26%23x201C%3Bal-Zab%26%23x16B%3Br%20al-shar%26%23x12B%3Bf%3A%20Nuskha%20ukhr%26%23x101%3B%20minhu.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BMajallat%20al-Majma%26%23x2BF%3B%20al-%26%23x2BF%3BIlm%26%23x12B%3B%20al-%26%23x2BF%3BArab%26%23x12B%3B%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2013%20%281933%29%3A%20341%26%23x2013%3B42.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DLNRUXFJN%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22al-Zab%5Cu016br%20al-shar%5Cu012bf%3A%20Nuskha%20ukhr%5Cu0101%20minhu%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22%5Cu02bfAbd%20All%5Cu0101h%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Mukhli%5Cu1e63%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221933%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22mukhlisAlZaburAlsharifNuskha1933%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22ar%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22G2YLCCCT%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Sadan%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221986%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BSadan%2C%20J.%20%26%23x201C%3BSome%20Literary%20Problems%20Concerning%20Judaism%20and%20Jewry%20in%20Medieval%20Arabic%20Sources.%26%23x201D%3B%20In%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BStudies%20in%20Islamic%20History%20and%20Civilization.%20In%20Honour%20of%20Professor%20David%20Ayalon%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%20edited%20by%20M.%20Sharon%2C%20353%26%23x2013%3B98.%20Jerusalem%3B%20Cana%3B%20Leiden%3A%20Brill%2C%201986.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DG2YLCCCT%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22bookSection%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Some%20Literary%20Problems%20Concerning%20Judaism%20and%20Jewry%20in%20Medieval%20Arabic%20Sources%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22J.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Sadan%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Sharon%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22bookTitle%22%3A%22Studies%20in%20Islamic%20History%20and%20Civilization.%20In%20Honour%20of%20Professor%20David%20Ayalon%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221986%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22sadanLiteraryProblemsConcerning1986%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22QAQF4D54%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Vishanoff%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222011%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BVishanoff%2C%20David%20R.%20%26%23x201C%3BAn%20Imagined%20Book%20Gets%20a%20New%20Text%3A%20Psalms%20of%20the%20Muslim%20David.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BIslam%20and%20Christian-Muslim%20Relations%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2022%2C%20no.%201%20%282011%29%3A%2085%26%23x2013%3B99.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DQAQF4D54%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22An%20Imagined%20Book%20Gets%20a%20New%20Text%3A%20Psalms%20of%20the%20Muslim%20David%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Vishanoff%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222011%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22vishanoffImaginedBookGets2011%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220959-6410%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22ECRV9WYC%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Vishanoff%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222011%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BVishanoff%2C%20David%20R.%20%26%23x201C%3BIslamic%20%26%23x2018%3BPsalms%20of%20David.%26%23x2019%3B%26%23x201D%3B%20In%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BChristian-Muslim%20Relations%3A%20A%20Bibliographical%20History.%20Volume%203%20%281050-1200%29%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%20edited%20by%20David%20Thomas%20and%20Alexander%20Mallett%2C%203%3A724%26%23x2013%3B30.%20Leiden%3A%20Brill%2C%202011.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DECRV9WYC%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22bookSection%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Islamic%20%5Cu2018Psalms%20of%20David%5Cu2019%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Thomas%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22editor%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Alexander%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Mallett%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Vishanoff%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22bookTitle%22%3A%22Christian-Muslim%20Relations%3A%20A%20Bibliographical%20History.%20Volume%203%20%281050-1200%29%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222011%22%2C%22originalDate%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPublisher%22%3A%22%22%2C%22originalPlace%22%3A%22%22%2C%22format%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-90-04-21616-7%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22vishanoffIslamicPsalmsDavid2011%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22SIRPCNZ8%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Vishanoff%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222010%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BVishanoff%2C%20David%20R.%20%26%23x201C%3BWhy%20Do%20the%20Nations%20Rage%3F%20Boundaries%20of%20Canon%20and%20Community%20in%20a%20Muslim%26%23x2019%3Bs%20Rewriting%20of%20Psalm%202.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BComparative%20Islamic%20Studies%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%206%2C%20no.%201%26%23x2013%3B2%20%282010%29%3A%20151%26%23x2013%3B79.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DSIRPCNZ8%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Why%20Do%20the%20Nations%20Rage%3F%20Boundaries%20of%20Canon%20and%20Community%20in%20a%20Muslim%5Cu2019s%20Rewriting%20of%20Psalm%202%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%20R.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Vishanoff%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222010%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22vishanoffWhyNationsRage2010%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22FN3AZHX9%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A538215%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22lastModifiedByUser%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A752752%2C%22username%22%3A%22nathanpgibson%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Nathan%20P.%20Gibson%22%2C%22links%22%3A%7B%22alternate%22%3A%7B%22href%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.zotero.org%5C%2Fnathanpgibson%22%2C%22type%22%3A%22text%5C%2Fhtml%22%7D%7D%7D%2C%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Zwemer%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221915%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%201.35%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BZwemer%2C%20S.%20M.%20%26%23x201C%3BA%20Moslem%20Apocryphal%20Psalter.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BMoslem%20World%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%205%2C%20no.%204%20%281915%29%3A%20399%26%23x2013%3B403.%20%26lt%3Ba%20title%3D%26%23039%3BCite%20in%20RIS%20Format%26%23039%3B%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-CiteRIS%26%23039%3B%20data-zp-cite%3D%26%23039%3Bapi_user_id%3D538215%26amp%3Bitem_key%3DFN3AZHX9%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bjavascript%3Avoid%280%29%3B%26%23039%3B%26gt%3BCite%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B%20%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20Moslem%20Apocryphal%20Psalter%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22S.%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Zwemer%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221915%22%2C%22section%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22partTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22citationKey%22%3A%22zwemerMoslemApocryphalPsalter1915%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22PMCID%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%220027-4909%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222026-02-17T10%3A28%3A48Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D

Mukhtār, Yaʿqūb al-, ed.

Mawāʿiẓ balīgha min Zabūr sayyidinā Dāwūd ʿalayhi al-salām wa-ghayrihi min al-kutub al-munazalla wa-jumlatuhā thalāthūna sūratan . Cairo: مطبعة مصطفى البابي, 1937.

Cite

Mukhtār, Yaʿqūb al-, and يعقوب المختار, eds.

مواعظ بليغة من زبور سيدنا داود عليه السلام وغيره من الكتب المنزلة || Sermons from the Psalms of David (Peace be upon him) and other Inspired Books . Cairo || القاهرة: مصطفى البابي الحلبي وأولاده, 1936.

Cite

Cheikho, Louis. “Quelques Légendes Islamiques Apocryphes.”

Mélanges de la Faculté orientale Beyrouth 4 (1910): 33–56.

Cite

Déclais, Jean-Louis.

David raconté par les musulmans . Patrmoines Islam. Paris: Editions du Cerf, 1999.

Cite

Hurvitz, Nimrod. “Biographies and Mild Asceticism. A Study of Islamic Moral Imagination.”

Studia Islamica , no. 85 (1997): 41–65.

Cite

Khoury, Raif Georges. “Quelques Réflexions sur les citations de la Bible dans les premières générations islamique du et du deuxième siècle de l’Hégire.”

Bulletin d’études orientales 29 (1977): 269–78.

http://www.jstor.org.0011f5uj08a3.emedia1.bsb-muenchen.de/stable/pdf/41604624.pdf?refreqid=search:0e25e21962886ec51d70f7a8d340b77c .

Cite

Khoury, Raif Georges.

Wahb b. Munabbih. Teil 1: Der Heidelberger Papyrus PSR Heid Arab 23. Leben und Werk des Dichters. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1972.

Cite

Krarup, Ove Chr., ed.

Auswahl Pseudo-Davidischer Psalmen: Arabisch und Deutsch. Copenhagen: G.E.C. Gad, 1909.

Cite

Melchert, Christopher. “Exaggerated Fear in the Early Islamic Renunciant Tradition.”

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Series 3 21, no. 3 (2011): 283–300.

Cite

Melchert, Christopher. “The Transition from Asceticism to Mysticism at the Middle of the Ninth Century C.E.”

Studia Islamica , no. 83 (1996): 51–70.

Cite

Melchert, Christopher. “The Islamic Literature on Encounters between Muslim Renunciants and Christian Monks.” In

Medieval Arabic Thought. Essays in Honour of Fritz Zimmermann , edited by Rotraud Hansberger, M. Afifi al-Akiti, and Charles Burnett, 135–42. London: The Warburg Institute, 2012.

Cite

Melchert, Christopher. “Quotations of Extra-Qur’ānic Scripture in Early Renunciant Literature.” In

Islam and Globalisation. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Proceedings of the 25th Congress of l’Union Européenne Des Arabisants et Islamisants , edited by Agostino Cilardo, 97–107. Leuven: Peeters, 2013.

Cite

Mukhliṣ, ʿAbd Allāh. “al-Zabūr al-sharīf.”

Majallat al-Majmaʿ al-ʿIlmī al-ʿArabī 12 (1932): 627–30.

Cite

Mukhliṣ, ʿAbd Allāh. “al-Zabūr al-sharīf: Nuskha ukhrā minhu.”

Majallat al-Majmaʿ al-ʿIlmī al-ʿArabī 13 (1933): 341–42.

Cite

Sadan, J. “Some Literary Problems Concerning Judaism and Jewry in Medieval Arabic Sources.” In

Studies in Islamic History and Civilization. In Honour of Professor David Ayalon , edited by M. Sharon, 353–98. Jerusalem; Cana; Leiden: Brill, 1986.

Cite

Vishanoff, David R. “An Imagined Book Gets a New Text: Psalms of the Muslim David.”

Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 22, no. 1 (2011): 85–99.

Cite

Vishanoff, David R. “Islamic ‘Psalms of David.’” In

Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History. Volume 3 (1050-1200) , edited by David Thomas and Alexander Mallett, 3:724–30. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Cite

Vishanoff, David R. “Why Do the Nations Rage? Boundaries of Canon and Community in a Muslim’s Rewriting of Psalm 2.”

Comparative Islamic Studies 6, no. 1–2 (2010): 151–79.

Cite

Zwemer, S. M. “A Moslem Apocryphal Psalter.”

Moslem World 5, no. 4 (1915): 399–403.

Cite

The “Psalms of David” as reimagined and rewritten by Muslims | David Vishanoff

[…] “The ‘Psalms of David’ as reimagined and rewritten by Muslims.” Biblia Arabica blog. May 14, 2019. https://biblia-arabica.com/the-psalms-of-david-as-reimagined-and-rewritten-by-muslims/ […]

Abu Yusuf Hasan Falero

Beautiful