by Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala

Codex Sinai Arabic 1 (Sin. Ar. 1) is one of the jewels of Christian Arabic translation literature.[1]A digitised copy of the codex is available on the website Sinai Manuscripts Digital Library: https://sinaimanuscripts.library.ucla.edu/catalog/ark:%2F21198%2Fz18w4z1w. The codex contains Arabic versions of the books of Job, Daniel (including the additions in ch. 3 and the narrative of Bel and the Dragon), Jeremiah, Lamentations and Ezekiel, which constitute an important part of the oldest corpus of South Palestinian Melkite translations of biblical texts that have survived,[2]Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam, Princeton – Oxford, 2008, pp. 50-53; idem, “Les premières versions árabes de la Bible … Continue reading all dating from the 9th century.[3]Margaret Dunlop Gibson, Catalogue of the Arabic Mss. in the Convent of S. Catharine on Mount Sinai, Cambridge, 1894, p. 1; Aziz Suryal Atiya, The Arabic Manuscripts of Mount Sinai, Baltimore, 1955, … Continue reading

2. The text of the book of Job was dismembered from the original codex by Constantin Tischendorf (1815–1874), and a substantial part of it is now in London, in the British Library: BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116).[4]William Cureton and Charles Rieu, Catalogus codicum manuscriptorum orientalium qui in Museo Britannico asservatur: Pars secunda codices arabicos amplectens, London, 1846-1871, pp. 675-676. Cf. … Continue reading In the second half of the nineteenth century, Wolf Wilhelm Graf von Baudissin (1847–1926) carried out the edition, accompanied by his study, of this dismembered section of the book of Job, specifically of the first twenty-eight chapters (1:8b-28:21a), an edition that has recently been revised and completed in the edition adding the unpublished text of Sin. Ar. 1.[5] Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, Libro de Job en version árabe (códice árabe sinaítico 1, s. IX): Edición diplomática con aparato crítico y estudio, Madrid: Sindéresis, 2022.

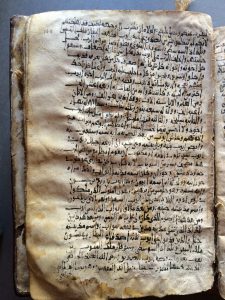

3. The Arabic version of the book of Job contained in BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1 is of great relevance in order to know the enterprise undertaken by the first Melkite translators who worked in the scriptoria of southern Palestine monasteries,[6]S.H. Griffith, The Bible in Arabic: The Scriptures of the “People of the Book” in the Lanaguage of Islam, Princeton – Oxford, 2013, pp. 108-122. Cf. S.H. Griffith, “The monks of Palestine and … Continue reading whose translation work is part of a long chain begun centuries earlier by the Aramaic translators who poured texts from Hebrew, but mainly from Greek, into Syriac Aramaic and Palestinian Christian Aramaic. The physical condition of the codex is good, although it exhibits moisture marks and tears in some of the folios (1r-v(S), 2r-v(S), 6r-v(S) et passim). Fol. 95v is currently illegible in the digitised reproduction of the text. The last folio (148v) contains a text telling us of the adventure of a preacher escaping from the hands of the Fatimid caliph al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh (996-1021 CE), which is the work of a well-known copyist monk named Christodoulos (Χριστόδουλος > ar. Akhrisṭū dūlūs), whose Arabic name responds to that of Ṣāliḥ b. Saʿīd al-Masīḥī, a name that likewise appears in other manuscripts in the library of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai.[7]Miriam L. Hjälm, Christian Arabic Versions of Daniel: A Comparative Study of Early MSS and Translation Techniques in MSS Sinai Ar. 1 and 2, Boston – Leiden, 2016, p. 76. About this copyist, see … Continue reading The text contained in BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1 is written on parchment. The codex consists of a total of 148 folios, measures 23 x 16 cms, the writing block measures 18.5 x 12.5 cms, and the number of lines on the folios is irregular, although it usually has 24-25 lines per folio page. The copyist of the codex used black ink for the text and red for the titles of the books and, occasionally, for the sections (aṣḥāḥ) of the texts, as well as for two textual dividers used throughout the codex: one in the form of a circle (with a dot inscribed in black ink), which appears sporadically, and whose function is to mark the division of verses and sentences; and another in the form of a cross based on five dots, one of them inscribed.[8]H.L. Fleischer, “Zur Geschichte der arabischen Schrift”, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Geselllschaft 18 (1864), p. 288. The codex has been numbered with Arabic numerals in recent times, although the numbering of the booklets in Rūmī numerals is preserved (fol. 8r(S) ff.).

4. The translations of the books included in Sin. Ar. 1 are introduced by a descriptive note of the text of paraphrastic character accompanied by a final formula of thanksgiving to God. The text of Job lacks a title, as well as the first seven verses and part of the eighth, although it must have possessed the title, which may have been Qiṣṣat Ayyūb al-nabī (“Tale of the prophet Job”) or Qiṣṣat Ayyūb al-ṣiddīq (“Tale of Job the pious”), as it appears in the versions contained in codices Sin. Ar. 514 and Sin. Ar. NF Parch. 18. [9]Sin. Ar. 514, fol. 141v. Cf. Sifr Ayyūb. Qāma bi-tarjamatihi min al-suryāniyyah ilā al-ʿarabiyyah Tūmā al-Fusṭāṭī fī al-qarn al-tāsiʿ al-mīlādī. Ed. Būlus ʻIyyād ʻIyyād, … Continue reading The version of the book of Job included in Sin. Ar. 514, dated to the ninth century,[10]Cf. A.S. Atiya, Arabic Manuscripts, p. 19; M. Kamil, Catalogue, p. 42. See Peter Tarras, “Thomas of Fustat: Translator or Scribe?”, available at … Continue reading as with the book of Daniel, also opens with the trinitarian basmala (bi-smi l-Ab wa-l-Ibn wa-l-Rūḥ al-Qudus), which closes with the usual unitary formulation (ilah wāḥid). It is possible, then, that this was the basmala borne by the Arabic version of the Book of Job in BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1, although obviously we cannot rule out the Islamic formula either, as is the case in the version contained in Sin. Ar. NF Parch. 18,[11]Cf. Y.E. Meimaris, Katalogos, p. 84, photo nº 23. which is also the one included in the versions of the books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel in Sin. Ar. 1.

5. The writing type used in the book of Job, as is the case with the other versions contained in Codex Sin. Ar. 1, is the calligraphic variety that Déroche has described as “new [Abbasid] style”,[12]François Déroche, The Abbasid Tradition: Qur’ans of the 8th to 10th centuries AD, London, 1992, pp. 132-183. a type of writing that, together with the support used, parchment, allows us to date the codex to the ninth century. This type of “neo-Abbasid” writing corresponds, in fact, to an ‘evolving kufic’ characteristic of the South Palestinian Christian Arabic texts of the ninth century, although somewhat less cursive than that exhibited by other contemporary manuscript witnesses.[13]M.L Hjälm, Christian Arabic Versions of Daniel, pp. 74-75.

6. The text, with annotations in the margins of some folios (21v, 22r, 24r, 27r, etc.), exhibits the orthographic characteristics typical of manuscripts of this period: frequent omissions of diacritics, absence of vowels, generalized omission of shaddah and hamzah in any of their positions, diverse consonantal changes (/t/ < /th/, /s/ < /sh/, /ṣ/ < /ḍ/, /ḍ/ < /ẓ/), as well as the realization of the consonant fāʾ with a dot above it and of qāf with a dot below it, although sometimes qāf also has the two diacritics.[14]J.P. Monferrer-Sala, “Once Again on the Earliest Christian Arabic Apology: Remarks on a Palaeographic Singularity”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 69/2 (2010), pp. 195-197; Bernhard Levin, Die … Continue reading The absence of diacritics is not always due to an allophonic confusion of the phonemes in question, but to an allographic practice in which the graphemes dispense with diacritics, which, in turn, are replaced by prolongations of graphemes that, in general, precede the consonant in question, or are found in the line above or below the one occupied by that consonant.

7. Undoubtedly, one of the most interesting aspects is the question of the Vorlage or Vorlagen that the translator of the Arabic version of the book of Job may have used. We know that its translator used as a basis a Syro-Hexaplar version,[15]G. Graf, GCAL, I, p. 126. whose text we unfortunately do not know due to the scarcity of syro-hexaplaric materials.[16]Arthur Vööbus, Discoveries of very important manuscript sources for the Syro-Hexapla: Contributions to the Research of the Septuagint, Stockholm, 1970, p. 3. In addition, the Arabic version of the book of Job gathers readings exhibited by other Syriac versions such as the Peshiṭtā or various Greek witnesses of the Septuagint (LXX) family, texts from which other Arabic versions were made. Likewise, the similarities in some readings of the Arabic version also reach the early revisions of the LXX made by Aquila, Simmacchus or Theodotion. To the above must be added, also, an important number of testimonies of free translations, and even cases of free rewriting, in which the translator has resorted to different techniques and translation strategies among which the modulation technique[17]J.P. Monferrer-Sala, “Preliminares sobre las lecturas syro-hexaplares contenidas en el códice Sinaí árabe 1 (s. IX)”, in De la Higuera y el olivo. Estudios en torno a Beatriz Molina Rueda, ed. … Continue reading stands out, translation options to which the characteristics exhibited by the ancient Greek version of Job from the corpus of the LXX should not be alien,[18]Marieke Dhont, “The Cultural Outlook of Old Greek Job: A Reassessment of the Notion of Hellenization”, in Die Septuaginta: Geschichte – Wirkung – Relevanz. 6. Internationale Fachtagung … Continue reading given the textual problems posed by this book.[19]Harry M. Orlinsky, “Studies in the Septuagint of the Book of Job”, Hebrew Union College Annual 28 (1957), pp. 53-74; Juliane Eckstein, “The Idiolect Text and the Vorlage of Old Greek Job: A New … Continue reading

8. Taking into account what we have just pointed out, we must add that there are also cases in which the translator has resorted to the verbum e verbo technique, a fact which, combined with the above – that is, the coincidence with readings that also document manuscript witnesses of the LXX, or with readings that reflect the revisions of the LXX carried out by Aquila, Simmacchus or Theodotion – leads us to believe that it is most likely that the Arabic translator has used more than one text, both Syriac and Greek. But the Arabic version of the book of Job contained in BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1 does not always coincide with the known Syro-Hexaplar text, nor with the Greek witnesses of the LXX, nor with the Syriac translation of the Peshiṭtā. This may be due to the fact that the translator did not translate the Syro-Hexaplar base-text verbum e verbo, but interpreted it in a free version, or a free rewriting, using the technique of modulation.

9. Another interesting question posed by the Arabic version of the book of Job is whether the text contained in BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1 is the original text, or on the contrary is the revision of an earlier translation that we do not know at present. The question is difficult to solve, since to the best of our knowledge we have only two Arabic versions of the book of Job related to the one contained in codex BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1: the version contained in Sin. Ar. 514 (fols. 141v-160r), made by the celebrated copyist Tūmā al-Fusṭāṭī, and that of Sin. Ar. NF Parch. 18. The texts of both versions have been fixed on parchment, but in the first case the date of composition is the ninth century, while the second is from the tenth century.

10. The comparison of the Arabic version contained in BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1 with these two versions is unequal, since the version contained in Sin. Ar. NF Parch. 18 is of very little use, due to the very poor state of preservation of this codex, whose leaves are stuck together and detaching them would mean breaking them. On the other hand, the use for comparative purposes of the version preserved in Sin. Ar. 514 is complete and has allowed us to carry out a complete collation, which in our opinion serves to affirm that we are dealing with a revision of an earlier translation, whose text seems to be none other than that contained in BL Ar. 1475 (= Add. 26116) + Sin. Ar. 1.

Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala (M.A. 1995, Ph.D. 1996, University of Granada) is currently a Full Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at the University of Cordoba. His courses deal with Arabic language and literature, and Islamic history. He teaches Master courses in the University of Granada as invited professor in the Department of Semitic Studies. His research focuses on Christian Arabic literature in the Near East and in al-Andalus. He is the founding co-editor together with Prof. Samir Khalil Samir of Collectanea Christiana Orientalia, and member of scientific committee of the Series Biblia Arabica in Brill.

Suggested Citation: Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, “The Oldest Arabic Version of the Book of Job?”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 26 October 2023, URL: https://biblia-arabica.com/the-oldest-arabic-version-of-the-book-of-job/. License: CC BY-NC.

References

| ↑1 | A digitised copy of the codex is available on the website Sinai Manuscripts Digital Library: https://sinaimanuscripts.library.ucla.edu/catalog/ark:%2F21198%2Fz18w4z1w. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam, Princeton – Oxford, 2008, pp. 50-53; idem, “Les premières versions árabes de la Bible et leurs liens avec le syriaque”, in L’Ancien Testament en syriaque, ed. Françoise Briquel Chatonnet and Philippe Le Moigne, Paris, 2008, pp. 223-226. |

| ↑3 | Margaret Dunlop Gibson, Catalogue of the Arabic Mss. in the Convent of S. Catharine on Mount Sinai, Cambridge, 1894, p. 1; Aziz Suryal Atiya, The Arabic Manuscripts of Mount Sinai, Baltimore, 1955, p. 3; Murad Kamil, Catalogue of all Manuscripts in the Monastery of St. Catharine on Mount Sinai, Wiesbaden, 1970, p. 11; cf. Georg Graf, Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, 5 vols., Vatican City, 1944-47, I, pp. 126-127. |

| ↑4 | William Cureton and Charles Rieu, Catalogus codicum manuscriptorum orientalium qui in Museo Britannico asservatur: Pars secunda codices arabicos amplectens, London, 1846-1871, pp. 675-676. Cf. Wolfius Guil. Frid. Comes de Baudissin, Translationis antiquae arabicae libri Iobi: Quae supersunt nunc primum edita, Leipzig, 1870. |

| ↑5 | Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, Libro de Job en version árabe (códice árabe sinaítico 1, s. IX): Edición diplomática con aparato crítico y estudio, Madrid: Sindéresis, 2022. |

| ↑6 | S.H. Griffith, The Bible in Arabic: The Scriptures of the “People of the Book” in the Lanaguage of Islam, Princeton – Oxford, 2013, pp. 108-122. Cf. S.H. Griffith, “The monks of Palestine and the growth of Christian literature in Arabic”, The Muslim World 78 (1988), pp. 1-28. |

| ↑7 | Miriam L. Hjälm, Christian Arabic Versions of Daniel: A Comparative Study of Early MSS and Translation Techniques in MSS Sinai Ar. 1 and 2, Boston – Leiden, 2016, p. 76. About this copyist, see Alexander Treiger, “Ṣāliḥ b. Saʿīd al-Masīḥī”, in Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History (1350-1500), ed. David Thomas et al., Leiden – Boston, 2013, V, pp. 643-650. |

| ↑8 | H.L. Fleischer, “Zur Geschichte der arabischen Schrift”, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Geselllschaft 18 (1864), p. 288. |

| ↑9 | Sin. Ar. 514, fol. 141v. Cf. Sifr Ayyūb. Qāma bi-tarjamatihi min al-suryāniyyah ilā al-ʿarabiyyah Tūmā al-Fusṭāṭī fī al-qarn al-tāsiʿ al-mīlādī. Ed. Būlus ʻIyyād ʻIyyād, Cairo, 1975, p. 5; Yiannis E. Meimaris, Katalogos tōn neōn arabikōn cheirographōn tēs Hieras Monēs Hagias Aikaterinēs tou Orous Sina, Athens, 1985, p. 84, photo nº 23. |

| ↑10 | Cf. A.S. Atiya, Arabic Manuscripts, p. 19; M. Kamil, Catalogue, p. 42. See Peter Tarras, “Thomas of Fustat: Translator or Scribe?”, available at https://biblia-arabica.com/thomas-of-fustat-translator-or-scribe/#ftn7. |

| ↑11 | Cf. Y.E. Meimaris, Katalogos, p. 84, photo nº 23. |

| ↑12 | François Déroche, The Abbasid Tradition: Qur’ans of the 8th to 10th centuries AD, London, 1992, pp. 132-183. |

| ↑13 | M.L Hjälm, Christian Arabic Versions of Daniel, pp. 74-75. |

| ↑14 | J.P. Monferrer-Sala, “Once Again on the Earliest Christian Arabic Apology: Remarks on a Palaeographic Singularity”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 69/2 (2010), pp. 195-197; Bernhard Levin, Die griechisch-arabische Evangelien-Übersetzung Vat. Borg. Ar. 95 und Ber. orient. oct. 1108, Uppsala, 1938, pp. 12-16. |

| ↑15 | G. Graf, GCAL, I, p. 126. |

| ↑16 | Arthur Vööbus, Discoveries of very important manuscript sources for the Syro-Hexapla: Contributions to the Research of the Septuagint, Stockholm, 1970, p. 3. |

| ↑17 | J.P. Monferrer-Sala, “Preliminares sobre las lecturas syro-hexaplares contenidas en el códice Sinaí árabe 1 (s. IX)”, in De la Higuera y el olivo. Estudios en torno a Beatriz Molina Rueda, ed. María José Cano Pérez, Tania García Arévalo, and Doğa Filiz Subaşi, Granada, 2023, pp. 227-237. |

| ↑18 | Marieke Dhont, “The Cultural Outlook of Old Greek Job: A Reassessment of the Notion of Hellenization”, in Die Septuaginta: Geschichte – Wirkung – Relevanz. 6. Internationale Fachtagung veranstaltet von Septuaginta Deutsch (LXX.D), Wuppertal 21.–24. Juli 2016, ed. Martin Mesier et al, Tübingen, 2018, pp. 618-630. |

| ↑19 | Harry M. Orlinsky, “Studies in the Septuagint of the Book of Job”, Hebrew Union College Annual 28 (1957), pp. 53-74; Juliane Eckstein, “The Idiolect Text and the Vorlage of Old Greek Job: A New Argument for an Old Debate”, Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018), pp. 197-219. |

Leave a Reply