by Alexander Treiger

An analysis of Biblical citations in an Arabic Christian text can often help determine whether this text was originally written in Arabic or translated from another language, such as Greek, Syriac, or Coptic. In the case of The Noetic Paradise (al-Firdaws al-ʿaqlī) this analysis not only conclusively demonstrates that it is a translation (from Greek), but also sheds unexpected light on one Arabic translation of the Pauline Epistles.

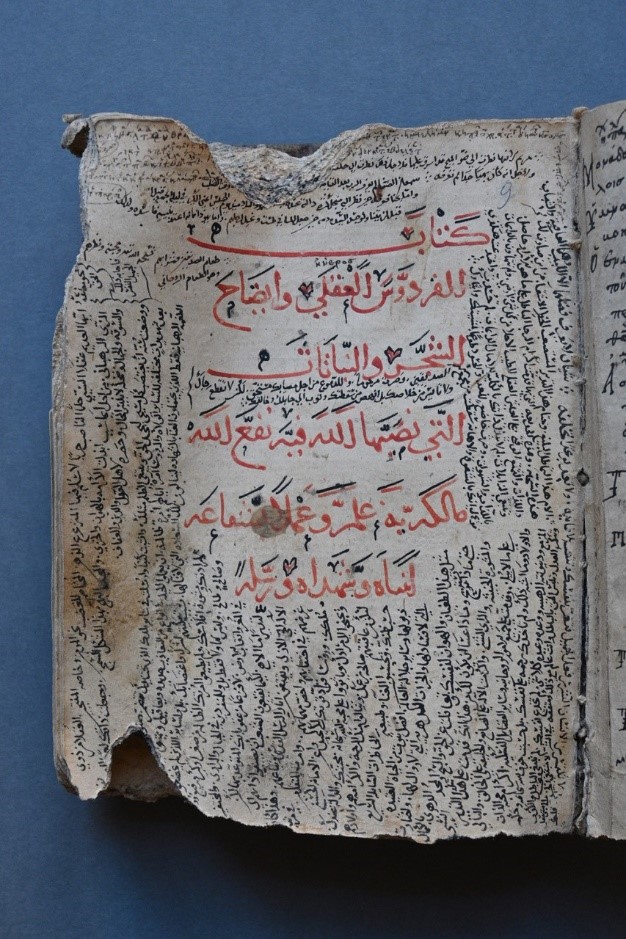

First, a few words on The Noetic Paradise are in order. This is an intriguing and rather lengthy mystical treatise which was quite popular among Arabic-speaking Christians from (at least) the twelfth century to the nineteenth, to judge from the large number of manuscripts (66 in total, the oldest – Sinai ar. 483 – dating to 1187). With the exception of the last chapter, The Noetic Paradise has not been edited, though some excerpts have been translated into English and Russian.[1]

The basic idea of The Noetic Paradise is that at the dawn of creation, human mind (ʿaql, corresponding to what both the Greek philosophers and the Church Fathers call νοῦς) fell from the realm to which it had originally belonged – the angelic world of contemplation. In its fallen state it is being constantly distracted by passions (anger, envy, lust, pride, acedia, vain glory, etc.) and, consequently, unable to contemplate. In line with much Greek Patristic literature, The Noetic Paradise urges us to fight against the passions, so as to attain the state of “dispassion” (ʿadam al-ālām, translating the Evagrian concept of ἀπάθεια) and to be readmitted into the angelic world of contemplation, our mind’s erstwhile homeland from which it was exiled.

What of the Biblical citations in The Noetic Paradise? There are dozens of them scattered throughout the treatise. In my initial soundings I decided to focus on those coming from the Pauline Epistles. I was hoping to see whether these citations matched any of the known Arabic translations of the Pauline Epistles. If they did, this would be a strong argument that The Noetic Paradise was originally written in Arabic – the author would then have simply lifted the citations from an Arabic Biblical translation at his disposal. If they did not, this could be circumstantial evidence in favour of the translation hypothesis (though, of course, this evidence would not be conclusive: the author could have used an Arabic translation that we do not know about or could have translated extemporaneously from memory).

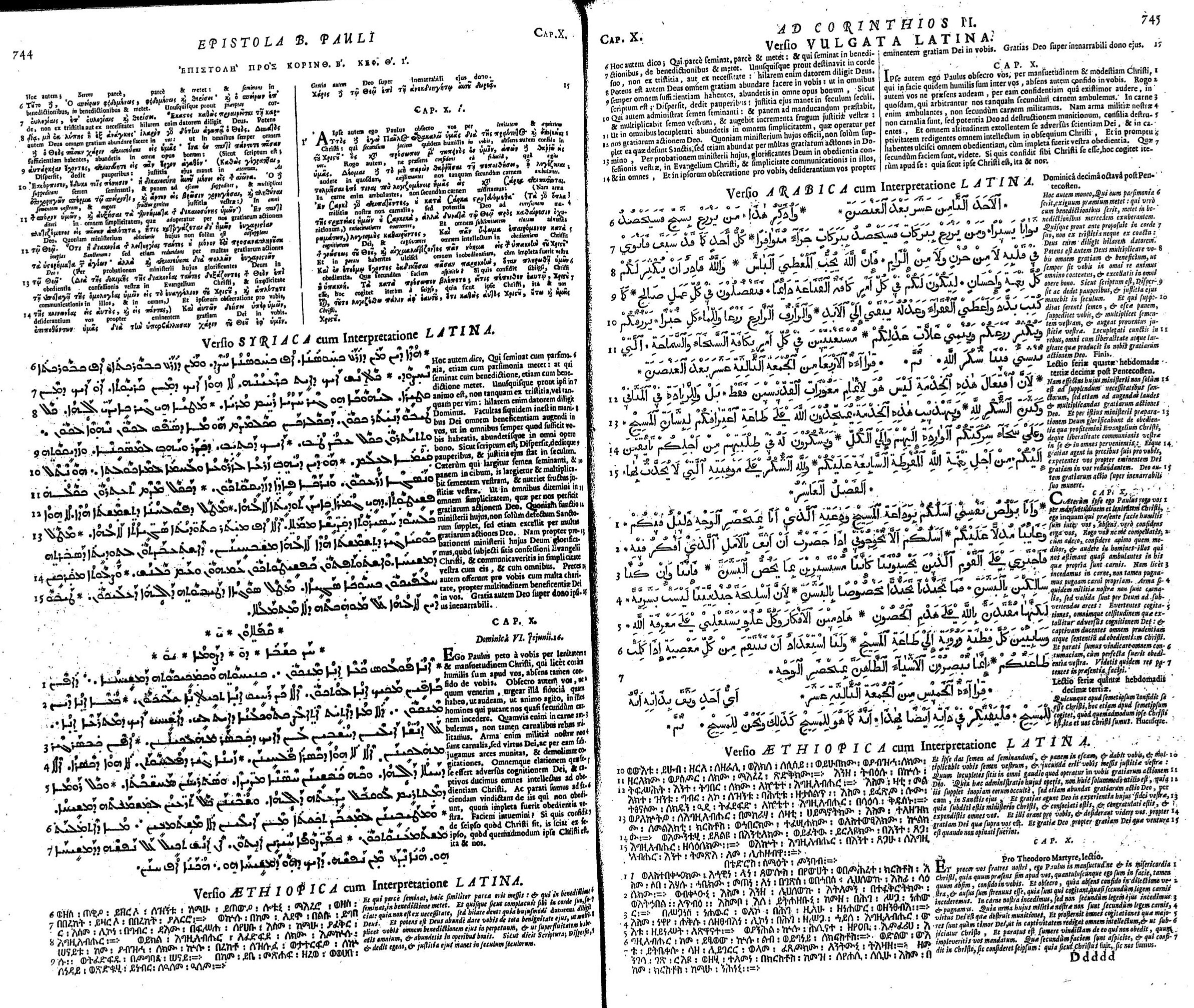

What I discovered, however, surprised me. On the one hand, the citations were strikingly similar to a particular Arabic translation of the Pauline Epistles – the one which Vevian Zaki in her landmark Munich PhD dissertation (supervised by Ronny Vollandt, soon to be published in Brill’s “Biblia Arabica” book series) has christened ArabGr3.[2] This translation is preserved in an Epistle lectionary (the oldest manuscript of which is Sinai ar. 169, dating to 1178) and was subsequently printed in the Paris and London Polyglot Bibles. On the other hand, however, the similarity was not close enough: the two texts frequently chose different words or turns of phrase to translate the same Greek lexical items; occasionally, it was even evident that the Arabic in the two cases reflected discordant Greek variants.[3]

Here is a characteristic example.

2 Cor. 10:3-5: 3 ἐν σαρκὶ γὰρ περιπατοῦντες οὐ κατὰ σάρκα στρατευόμεθα — 4 τὰ γὰρ ὅπλα τῆς στρατείας ἡμῶν οὐ σαρκικὰ ἀλλὰ δυνατὰ τῷ θεῷ πρὸς καθαίρεσιν ὀχυρωμάτων — λογισμοὺς καθαιροῦντες 5 καὶ πᾶν ὕψωμα ἐπαιρόμενον κατὰ τῆς γνώσεως τοῦ θεοῦ, καὶ αἰχμαλωτίζοντες πᾶν νόημα εἰς τὴν ὑπακοὴν τοῦ Χριστοῦ.

KJV: 3 For though we walk in the flesh, we do not war after the flesh: 4 (For the weapons of our warfare are not carnal, but mighty through God to the pulling down of strongholds;) 5 Casting down imaginations, and every high thing that exalteth itself against the knowledge of God, and bringing into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ.

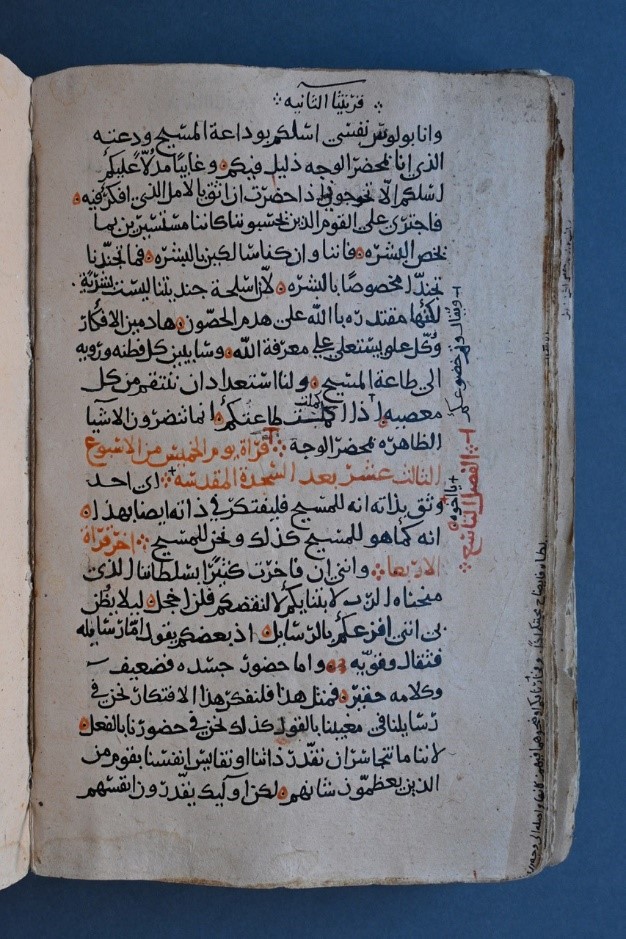

This is the translation in ArabGr3:

ـ3فانّنا وان كنّا سالكين بالبشرة فما تجنّدنا تجنّدًا مخصوصًا بالبشرة 4 لانّ اسلحة جنديّتنا ليست بشرية لكنّها مقتدرة بالله على هدم الحصون هادمين الافكار 5 وكلّ علوّ يستعلي على معرفة الله وسابيين كلّ فطنة ورويّة الى طاعة المسيح

And this is how this text is translated in The Noetic Paradise:

ـ3ولئن كنّا نمشي بالبشرة فلم نتجنّد بما يختصّ بالبشرة 4 لانّ اسلحة جنديّتنا ليست بشرية بل مقتدرة بالله على هدم الحصون وتنقض الافكار 5 وكلّ علوّ يتعالى على معرفة الله [[وسابية كلّ معقول]] // [[تستبي كلّ معقول ورويّة]] الى طاعة المسيح

(The alternative variants in double brackets appear on two distinct occasions when this passage is cited.)

The similarities between the two translations are obvious – and down to such an idiosyncratic feature as the rendering of the Greek σάρξ (“flesh”) as بشرة (presumably pronounced bašara or bišra), under the influence of the Syriac ܒܣܪܐ (besrā, “flesh”). (In ordinary Arabic, by contrast, bašara means “skin.”)

Nonetheless, it seems out of the question that the author of The Noetic Paradise was simply citing ArabGr3. The discrepancies are all too apparent. Though some may be explained on stylistic grounds (it is conceivable, for example, that the author of The Noetic Paradise could have changed ما تجنّدنا into لم نتجنّد, etc.), others cannot be explained this way.

Most crucially, ArabGr3 renders the Greek participles καθαιροῦντες and αἰχμαλωτίζοντες (KJV: “pulling down” and “bringing into captivity” respectively) by masculine plural Arabic participles هادمين and سابيين. The Noetic Paradise, by contrast, uses feminine singular verbal and participial forms تنقض and تستبي / سابية. The underlying Greek text of The Noetic Paradise version must therefore have featured neuter plural participles καθαιροῦντα and αἰχμαλωτίζοντα, referring to ὅπλα, “weapons,” hence the feminine singular (i.e., inanimate plural) forms in the Arabic translation.[4]

The fact that ArabGr3 and The Noetic Paradise reflect discordant Greek variants proves that they are INDEPENDENT translations (both done from Greek). The fact that they are, nonetheless, so strikingly similar shows that these are two independent translations PRODUCED BY THE SAME TRANSLATOR.

This is a crucial piece of information which has far-reaching consequences for both ArabGr3 and The Noetic Paradise. The histories of these two texts are bound together. They must have been rendered into Arabic by the same person, presumably in the same location (unless the translator travelled from place to place) and at roughly the same time. If we can identify further Arabic translations produced by the same person (and I believe this can be done), we will learn more about the provenance (i.e., the translation milieu) of both ArabGr3 and The Noetic Paradise.

Though more research is needed to substantiate this conclusion, I believe textual evidence strongly suggests that both texts were translated into Arabic in Antioch or one of the surrounding monasteries in the late tenth or the first half of the eleventh century.[5]

Alexander Treiger (PhD 2008, Yale University) is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is editor of the series “Arabic Christianity: Texts and Studies” (Brill) and co-editor of The Orthodox Church in the Arab World (700-1700): An Anthology of Sources (2014), Heirs of the Apostles: Studies on Arabic Christianity in Honor of Sidney H. Griffith (2019), and Patristic Literature in Arabic Translations (2020). His interests include Arabic and Syriac Christianity, Islamic philosophy, theology, and mysticism, Graeco-Arabic Studies, and transmission of ideas from Late Antiquity to early Islam.

Suggested Citation: Alexander Treiger, “The Noetic Paradise and Biblia Arabica”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 9 January 2020, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121817/.

Footnotes[1] For a list of manuscripts and a critical edition and English translation of the last chapter, see Alexander Treiger, “The Noetic Paradise (al-Firdaws al-ʿaqlī): Chapter XXIV,” in: Barbara Roggema and Alexander Treiger (eds.), Patristic Literature in Arabic Translations, Leiden: Brill, 2020, pp. 328-376; for a translation of excerpts, see Alexander Treiger, “The Noetic Paradise,” in: Samuel Noble and Alexander Treiger (eds.), The Orthodox Church in the Arab World (700-1700): An Anthology of Sources, DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2014, pp. 188-200 and 320-322; Александр Трейгер, “Умный рай: мистико-аскетический трактат в арабском переводе,” Символ 58 (2010): 297-316.

[2] I am deeply grateful to Vevian Zaki for generously sharing with me information on ArabGr3 and sending me a copy of her dissertation prior to publication.

[3] For further details, please consult Treiger, “The Noetic Paradise (al-Firdaws al-ʿaqlī): Chapter XXIV,” pp. 342-344.

[4] 2 Cor. 10:4 is paraphrased with καθαιροῦντα instead of καθαιροῦντες, e.g., in John Chrysostom’s On the Incomprehensible Nature of God, Homily I—see PG 48, col. 797; Jean Chrysostome, Sur l’incompréhensibilité de Dieu, Tome I (Homélies I-V) (Sources chrétiennes 28bis), ed. Anne-Marie Malingrey, trans. Robert Flacelière, Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1970, p. 130.

[5] As I hope to show in a future publication, the same translator is also behind many Arabic translations of Ephrem the Syrian. These particular Arabic Ephrem translations, as opposed to older ones produced in Palestine in the ninth century, make their first appearance in the eleventh century (in the eleventh-century manuscript Sinai ar. 312 + Sinai ar. NF Perg. 13, copied in the region of Antioch). Once the connection between ArabGr3 and The Noetic Paradise on the one hand and these Arabic translations of Ephrem has been securely proven, it will be possible more accurately to date both ArabGr3 and The Noetic Paradise. Together with these Arabic Ephrem versions, they would have to be dated to the eleventh century at the latest, and their provenance would have to be assigned to Antioch. On the Arabic Ephremiana, see especially Fr. Samir Khalil Samir’s articles “Le Recueil éphrémien arabe des 52 homélies,” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 39 (1973): 307-332; “Le recueil ephremien arabe des 30 homelies (Sinai Arabe 311),” Parole de l’Orient 4 (1973): 265-315; “Eine Homilien-Sammlung des Ephräm, der Codex Sinaiticus arabicus Nr 311,” Oriens Christianus 58 (1974): 51-75; “L’Éphrem arabe: État des travaux,” Orientalia Christiana Analecta 205 (1978): 229-242. This subject, of course, remains to be investigated further.

Leave a Reply