by Dennis Halft OP

The Imāmī (Twelver) Shiʿite scholar Sayyid Aḥmad ʿAlavī (d. between 1644 and 1650) is well-known for his Persian writings against Christianity.[1] Born in the Safavid capital of Isfahan, ʿAlavī was the intellectual spearhead of the local Shiʿite clergy against the Catholic missionaries who were active in the city from the late sixteenth century onwards. In the early 1620s, following the ‘Isfahan disputation’ between Catholic and Shiʿite representatives on theological matters, especially the Christian rejection of the prophethood of Muḥammad and of the Qurʾān, the relationship between the Shiʿite clergy and the missionaries deteriorated.[2] ʿAlavī composed a series of anti-Christian treatises in Persian, in which he offers an allegorical exegesis of biblical passages in favor of Muḥammad and Shiʿite imamology. He quotes, for instance, Genesis 17:20[3] which he interprets as a prediction of the advent of the twelve Imāms.[4] While this verse has been repeatedly reproduced by Twelver Shiʿite scholars, including ʿAlavī, our Shiʿite author also offers a more original interpretation of Gospel verses that have been rarely, or not at all, invoked by earlier Muslim writers on Christianity.

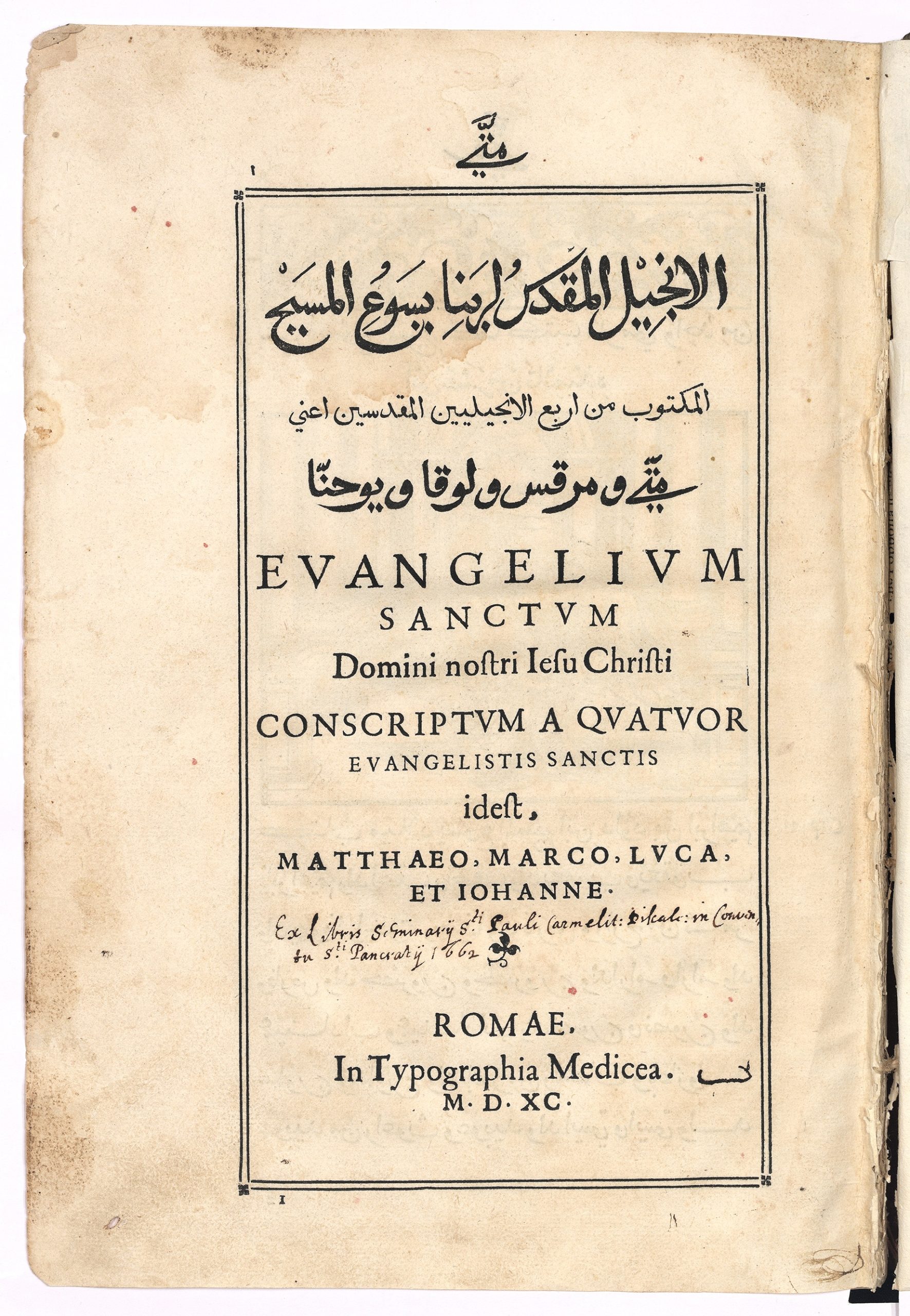

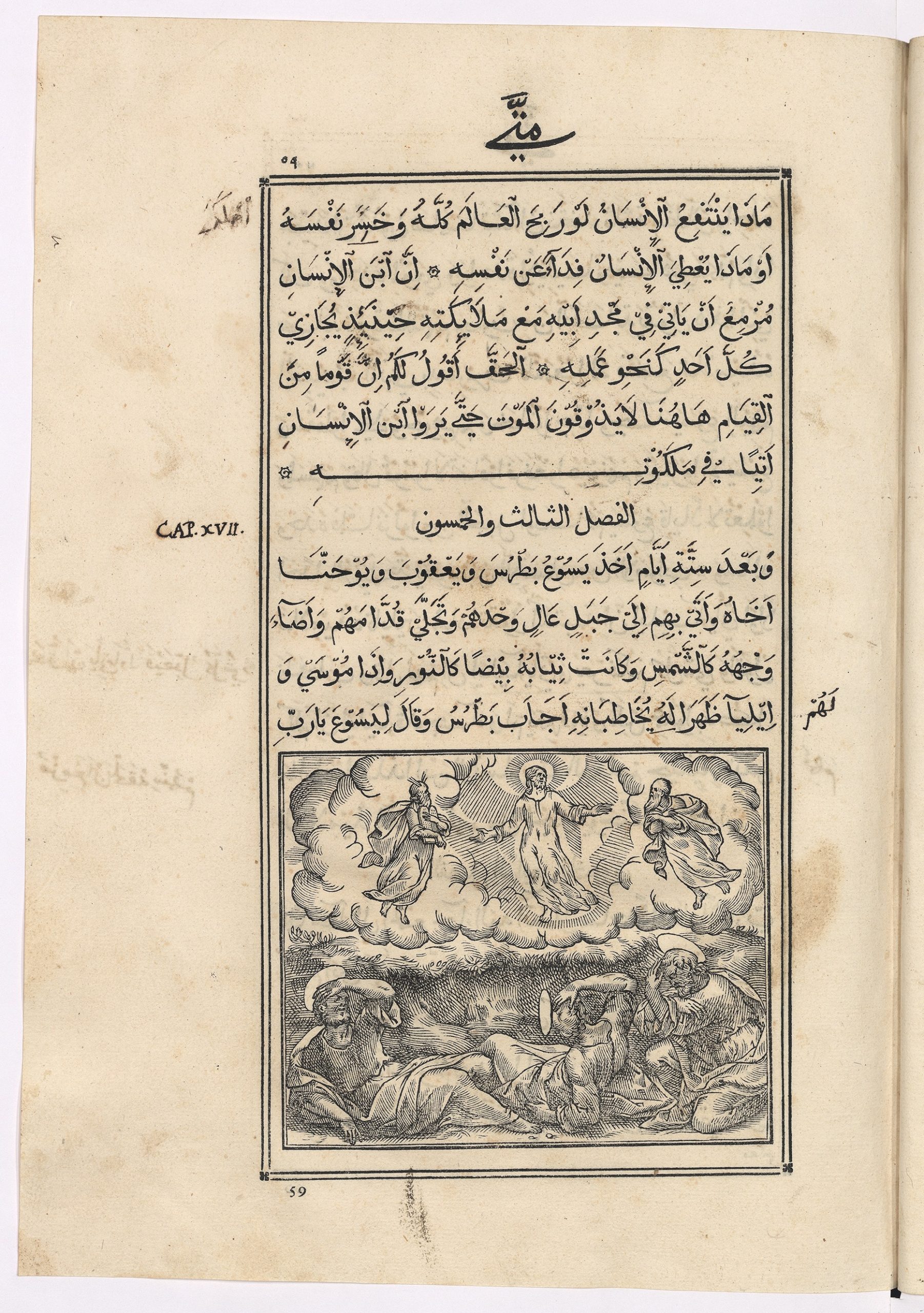

This can be explained by the fact that the Gospels were directly available to ʿAlavī through the ‘Roman Arabic Vulgate’, the first publication of the Gospels in Arabic translation, printed by the Medici Oriental Press in Rome in 1590/1.[5] Copies of the edition were imported by missionaries to Safavid Persia and became the preferred source of Shiʿite exegetes of the time for the study of the Christian Scriptures. The availability of a printed edition allowed ʿAlavī to scrutinize all four Gospels and to develop a comparatively elaborate Shiʿite exegesis. For example, in ʿAlavī’s most widely disseminated work: Miṣqal-i ṣafāʾ dar tajliya u taṣfiya-yi Āʾīna-yi ḥaqq-numā dar radd-i madhhab-i Naṣārā (‘The polisher of purity to burnish and make clear ‘The mirror showing the truth’ in refutation of the Christians’) dated 1622, our Shiʿite author draws extensively on Gospel passages referencing the Old Testament prophet Elijah.[6] He summarizes the pericope of the Transfiguration of Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels, according to which Elijah, along with Moses, appears and talks to the miraculously transformed Jesus.[7] In addition, he quotes verbatim Matthew 16:13-14[8] in a Persian translation made from the Arabic.

ʿAlavī’s main question is how to interpret the references to Elijah in the Gospels. Our Shiʿite author rejects the Christian tradition of identifying John the Baptist with Elijah, but instead identifies ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (d. 661), cousin and son-in-law of Muḥammad and first in the line of Shiʿite imāms, with Elijah. This is astonishing considering the long Shiʿite tradition of interpreting Jesus as ʿAlī and presenting him as the ‘second Jesus, Christ and Messiah’ without recourse to Elijah.[9] In contrast to earlier scholars, ʿAlavī aims at substantiating Shiʿite imamology by connecting ʿAlī with Jesus through the figure of Elijah. In addition, our Shiʿite author draws on the Illuminationist (ishrāqī) philosophical tradition and its distinction between the ‘imaginal world’ (ʿālam-i mithāl) and the world of witnessing (ʿālam-i shuhūd), in which things become manifest.[10] According to ʿAlavī, Elijah and Moses do not appear in human form, i.e. in bodies composed of elements (ba tarkīb-i ʿunṣurī), but as beings of the ‘imaginal world’. While Moses represents the time before the advent of Jesus, Elijah-ʿAlī does so for the time after Jesus’ death. In other words, Jesus is regarded as the precursor of the first Imām who supersedes him.

This example from ʿAlavī’s treatise shows that the availability of the printed Arabic Gospels in seventeenth-century Isfahan provoked a closer reading of the biblical text and led to a refinement of earlier Shiʿite interpretations of the relation between ʿAlī and Jesus.

Dennis Halft OP is a Martin Buber Fellow at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He received his doctorate in Islamic studies from the Free University of Berlin in 2017. He has published various articles on Islamic intellectual history, and is mainly interested in interreligious interaction in the Islamic Middle Ages and early modern Iran.

Suggested Citation: Dennis Halft, “Shi’ite Muslim Exegesis of the Bible in Early Modern Iran: Sayyid Aḥmad ʿAlavī and his Interpretation of Elijah”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 9 February 2020, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121818/.

Footnotes[1] On him, see Halft, “Sayyid Aḥmad ʿAlavī,” in: Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History, vol. 10 (Ottoman and Safavid Empires 1600-1700), ed. D. Thomas and J. Chesworth, Leiden: Brill, 2017, 529-546.

[2] For details, see Halft, “Pietro della Valle. Risāla-yi Piṭrūs dillā Vāllī,” in: Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History, vol. 10 (Ottoman and Safavid Empires 1600-1700), ed. D. Thomas and J. Chesworth, Leiden: Brill, 2017, 518-521.

[3] “As for Ishmael, I have heard you; I will bless him and make him fruitful and exceedingly numerous; he shall be the father of twelve princes, and I will make him a great nation.”

[4] See Halft, “Hebrew Bible Quotations in Arabic Transcription in Safavid Iran of the 11th/17th Century: Sayyed Aḥmad ʿAlavī’s Persian Refutations of Christianity,” Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 1 (2013), 235-252.

[5] For details, see Halft, Christianity Encounters Shīʿī Islam: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Arabic Gospels in Safavid Persia (Biblia Arabica), Leiden: Brill (forthcoming, 2020).

[6] For ʿAlavī’s quotation and interpretation, see his Miṣqal-i ṣafā dar naqd-i kalām-i masīḥiyyat, ed. Ḥ. N. Iṣfahānī, Qum: Amīr, [1994], 193-195. On Elijah in the Gospels, see M. Öhler, “Elia (NT),” in: Das wissenschaftliche Bibellexikon im Internet (WiBiLex), June 2010, https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/de/stichwort/47879/ [Accessed 12 May 2019].

[7] See Matthew 17:1-13; Mark 9:2-13; Luke 9:28-36.

[8] “Now when Jesus came into the district of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples, ‘Who do people say that the Son of Man is?’ And they said, ‘Some say John the Baptist, but others Elijah, and still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.’”

[9] See M. A. Amir-Moezzi, “Muḥammad the Paraclete and ʿAlī the Messiah: New Remarks on the Origins of Islam and of Shiʿite Imamology,” Der Islam 95 (2018), 30-64; idem, “‘Alī comme le Second Christ. De quelques très anciennes convergences entre shi’isme et christianisme,” Mélanges de l’Institut dominicain d’études orientales 35 (2020).

[10] For an introduction to this philosophical tradition, see J. Walbridge, “Suhrawardī and Illuminationism,” in: The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy, ed. P. Adamson and R. C. Taylor, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, 201-223; H. Ziai, “Philosophy of Illumination,” in: The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy, ed. J. L. Garfield and W. Edelglass, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011, 410-418.

Leave a Reply