by Tamar Zewi

The following is an outline of my findings while working on the identification and classification of early Genizah fragments of Saadya Gaon’s translation of the Pentateuch in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg and after recently conducting a research visit there. This work is part of a larger research project of mine on early Genizah fragments of Saadya Gaon’s translation of the Pentateuch supported by the ISRAEL SCIENCE FOUNDATION (grant no. 150/15).[1]

The earliest and most important manuscript containing Saadya’s translation of the Pentateuch is kept in the Russian National Library. This is MS St. Petersburg RNL Yevr. II C 1, copied by Samuel ben Jacob, which contains almost all the Pentateuch.[2] It is intended to be the main version used in a new critical edition of this translation.[3] While Blau discussed in detail the characteristics of Saadya’s translation in this manuscript,[4] my research of Genizah fragments in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg focused on identifying and examining other early Genizah fragments of Saadya’s translation of the Pentateuch in this collection.

So far I have identified about 100 such fragments, many containing only a few folios, made of parchment or paper. Most of these are very fragmentary and their state of preservation is extremely poor. Many are partly torn and none provide details concerning the copyist or the date when they were copied. Some of these fragments were previously identified as holding Saadya’s translation, but the exact type of Arabic translation of many others was not specified: these required further examination and classification. Low-resolution black and white images of most of the fragments in the Russian National Library can be observed on the Internet site of the National Library of Israel. Some of them are also displayed in the Friedberg Genizah Project (https://fjms.genizah.org/).

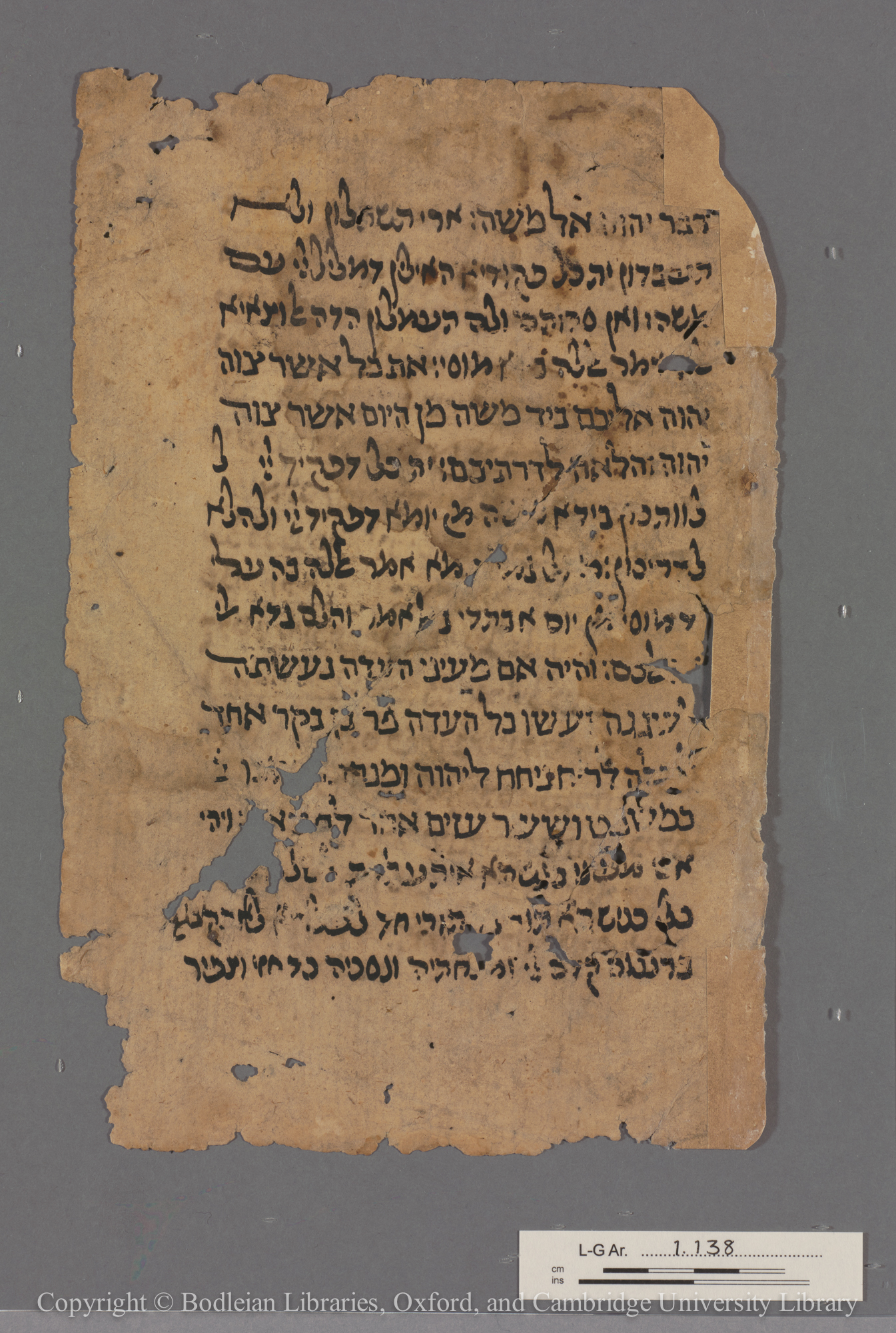

The fragments of Saadya’s translation of the Pentateuch in Hebrew characters kept in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg are no different from other fragments of this translation kept in other Genizah collections worldwide. The largest is the collection in the Cambridge University Library.[5] They include fragmentary remnants of manuscripts in which Saadya’s translation follows Hebrew incipits or full Hebrew verses, and occasionally triglots displaying the Hebrew verse, its Aramaic translation (Onkelos), and Saadya’s translation. Passages of Saadya’s translation are also found embedded in his exegesis, but these are fewer. Some of the fragments are written in square oriental script, others in semi-cursive script. The fragments are made of parchment or paper. Common words and proper nouns may be shortened, numbers are frequently conveyed in Hebrew characters and the transcription conventions to Hebrew characters mostly include diacritic points for צ’ (ض) and ט’ (ظ), occasionally also ג’ mostly representing ج and rarely غ. The versions of Saadya’s translation attested in these fragments are generally close to that of MS St. Petersburg RNL Yevr. II C 1, but also reveal minor differences.

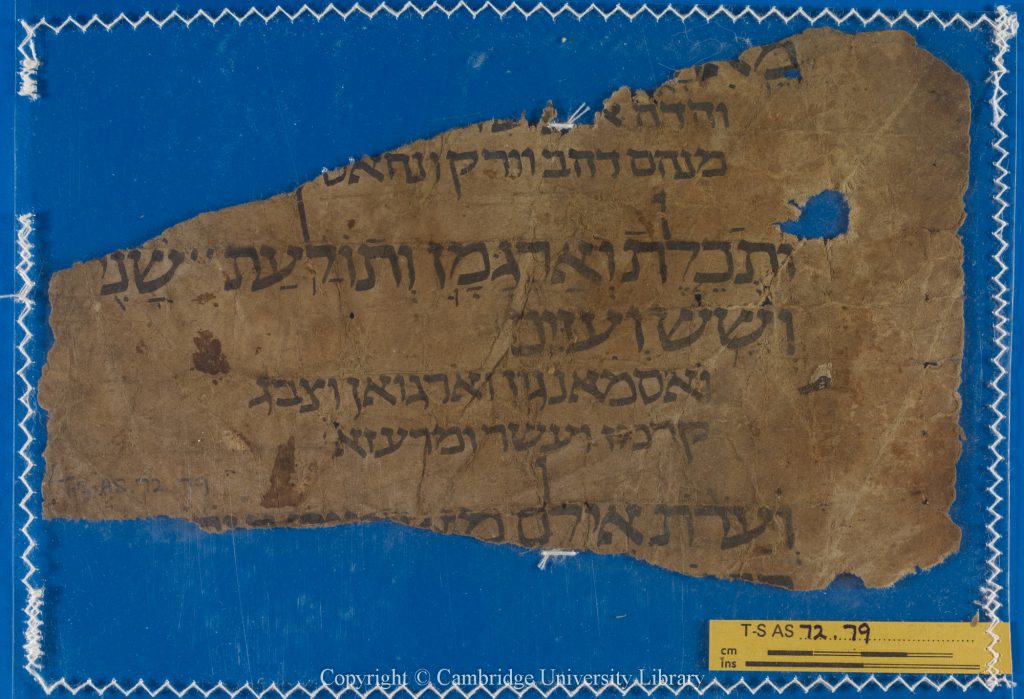

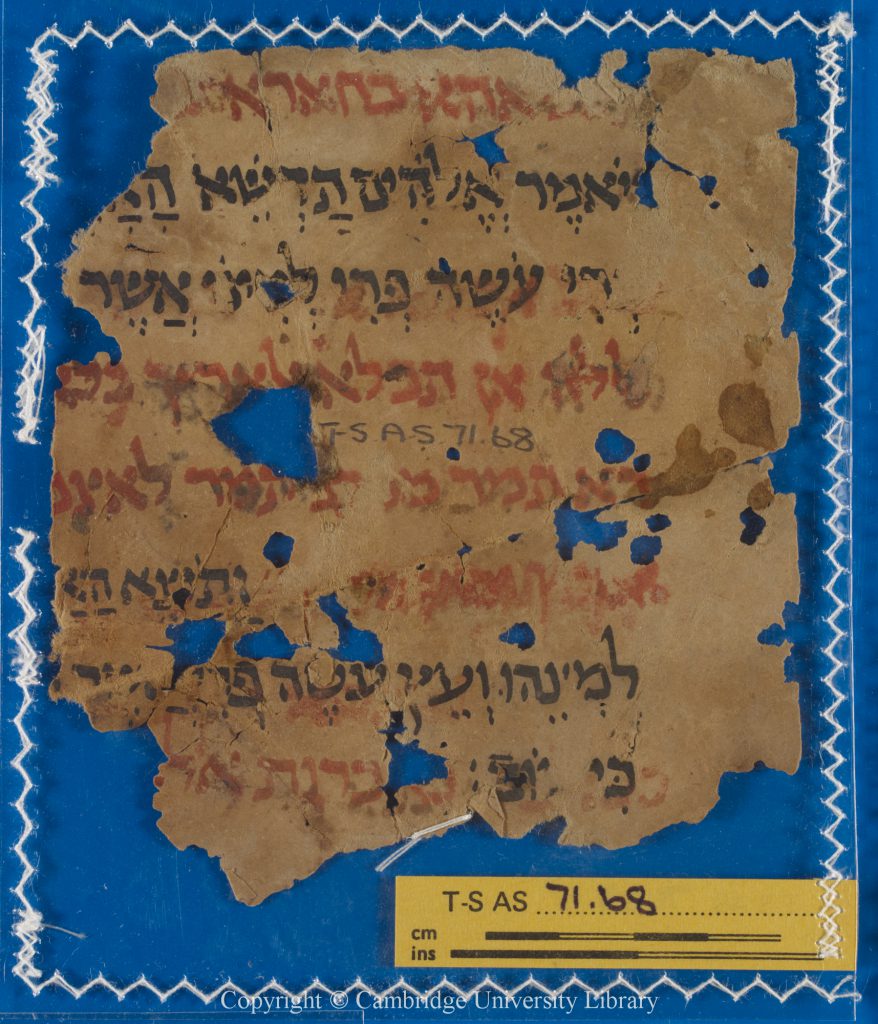

Hebrew text of Genesis 1:10–12 with Judaeo-Arabic translation by Saadiah Gaon. MS Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, T-S AS 71.68 recto. We are grateful to the syndics of the university library for permission to use this image.

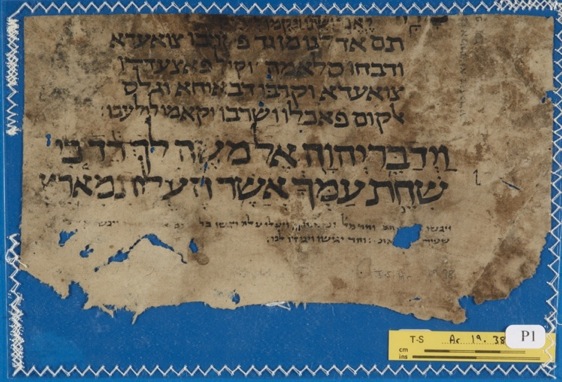

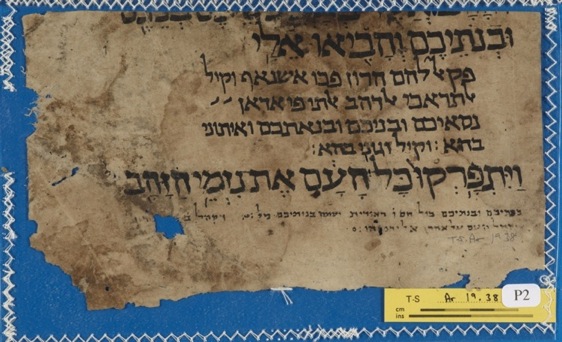

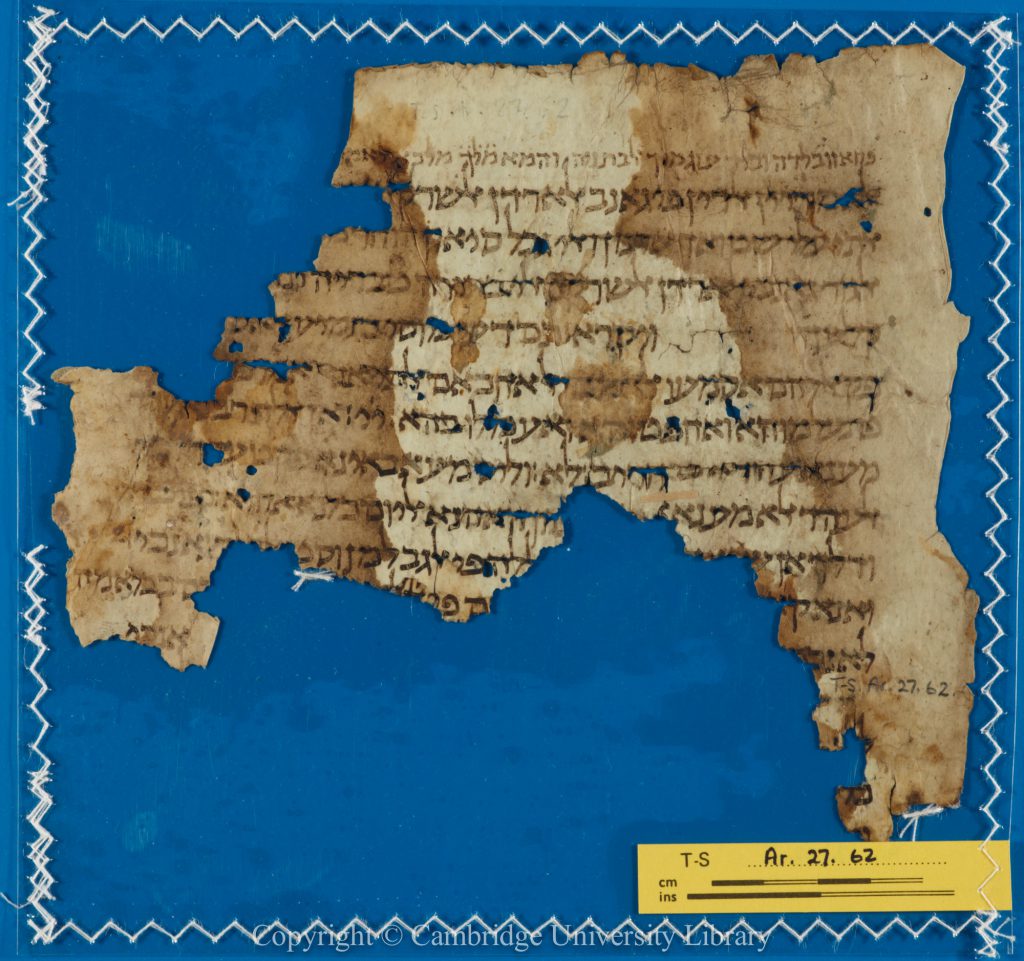

Judaeo-Arabic translation of Deuteronomy 4:47–5:5; 5:11–16 by Saadiah Gaon. MS Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, T-S Ar.27.62 recto. We are grateful to the syndics of the university library for permission to use this image.

One small fragment, MS St. Petersburg RNL Yevr. II A 640, containing two leaves made of parchment, discloses remnants of several Hebrew verses (Deuteronomy 4.31–35, 46–49, 5.1) accompanied by Masoretic vocalization, cantillations, and one Masoretic note; Saadya’s translation follows. This fragment, according to the shape of its characters, most probably belonged to a manuscript, unknown so far, copied by Samuel ben Jacob in the first quarter of the 11th century.[6] Worth mentioning is also one short fragment made of parchment in the form of a rotulus,[7] which does not contain any part of Saadya’s translation of the Pentateuch but rather of Daniel. This is Yevr. III B 642, which holds Dan. 6.15–29, 7.1-8. This fragment is similar to 15 other rotuli that Amir Ashur and I identified in other Genizah collections and prepared for publication.[8]

Tamar Zewi is a full Professor in the Department of Hebrew Language at the University of Haifa. Her topics of research are Hebrew and Semitic languages and Linguistics, Judeo-Arabic, and Arabic Bible Translations.

Dr. Amir Ashur’s research focuses on the ‘documentary Geniza’ – letters and legal documents, but he also covers other areas and genres in the Genizah such as Geonica, responsa and documents relating to medical practice. He is currently working with Prof. Tamar Zewi.

Suggested Citation: Tamar Zewi, “Early Genizah Fragments of Saadya Gaon’s Translation of the Pentateuch in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 18 December 2018, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121793/.

[1] I would like to thank Dr. Amir Ashur, for his great assistance in the project, Mr. Boris Zaykovsky, curator of the Oriental collections in the Manuscript Department at the National Library of Russia, my husband Gill Zewi, who worked with me at the National Library of Russia during our research visit there, and Dr. Barak Avirbach, who provided some of the transcriptions to Genizah fragments in this collection. The project in general and some of its results are discussed in Ashur and Zewi (forthcoming).

[2] This manuscript has many small lacunas and half of the book of Leviticus is missing from it.

[3] Schlossberg 2011.

[4] Blau 1998, 2001.

[5] E.g. Polliack 1998 on Arabic Bible translations in the Cambridge Genizah collection; Ashur & Zewi on Saadya’s Bible translation in the JTS Genizah collection.

[6] This fragment is described in detail in Zewi (submitted for publication). I thank Amir Ashur for confirming to me the identity of the copyist of this fragment. Similar fragments have been identified by Ronny Vollandt, cf. Two fragments (T-S AS 72.79 and T-S Ar.1a.38) of Saadiah’s tafsīr by Samuel ben Jacob.

[7] On rotuli in the Cairo Genizah see Olszowy-Schlanger 2016.

[8] Zewi & Ashur (forthcoming). We have also identified the copyist of these fragments.

Bibliography

The text of this page is copyright the author(s) and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Jay Travis

Thank you, Dr. Zewi, for this article on Saadya Gaon’s translation work. I have a question on how he rendered divine names. I know in his translations that he used the name Allah in reference to God. My question is, Did he translate only Elohim and its derivatives as Allah or did he render YHWH as Allah as well? I have seen Bible translations that do one or the other or both, and I would be curious, if you know, what Saadya Gaon did.

Thank you,

Jay Travis, PhD