A Review Essay by Meira Polliack

“And you think

That I don’t even mean

A single word I say

It’s only words

And words are all I have

to take your heart away”.[1]

Celebrating a new book by Robert Alter

Any book by Robert Alter, acclaimed literary critic, Bible translator and commentator, and Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley, is a cause for celebration. In this new work Alter has something for all who love literature worldwide, all who enjoy balanced and edifying literary criticism as he shares with us, in his engaging and flowing style, a thought-provoking account of his personal experience as a Bible translator.

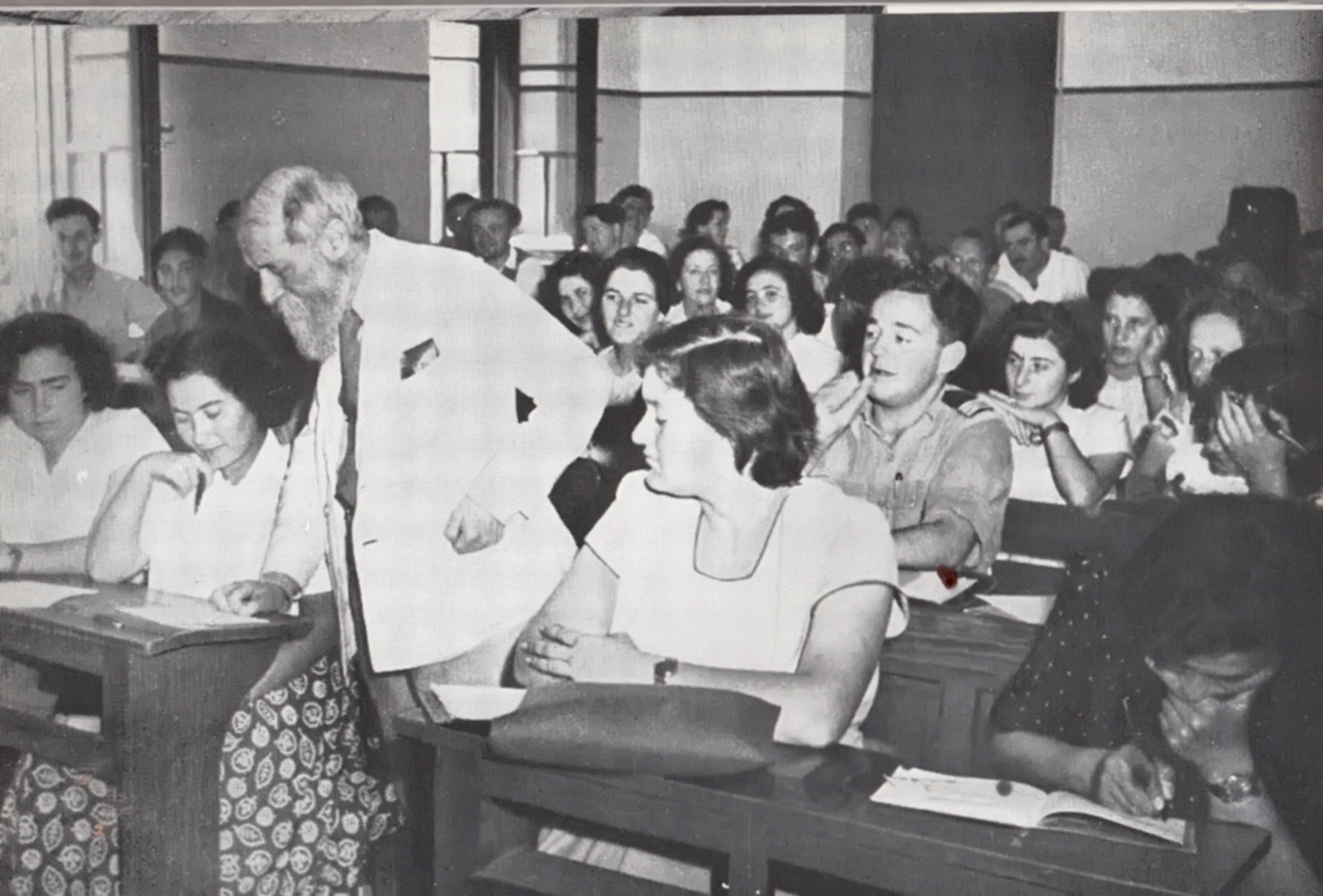

Alter among his peers

Alter’s enthrallment with biblical literature grew throughout the 1970s, and bore its first fruit in his groundbreaking work, The Art of Biblical Narrative (1981). He is one of a group of literary scholars who at around the same time “rediscovered” and revealed to the world, as modernists, the literary make-up of the Hebrew Bible. Some other names that spring to mind include Shimon Bar-Efrat, Adele Berlin, Athalya Brenner, David Clines, Jan Fokkelman, Edward Greenstein, David Gunn, Frank Kermode, James Kugel, Menachem Perry, Frank H. Polak, Uriel Simon, Meir Sternberg, Meir Weiss and Yair Zakovitch. Among these were no small number of literary critics, whose use of modern (Israeli) Hebrew – highly dependent on the Bible’s vocabulary, though less on its syntax – sensitized them to certain aspects of biblical style.

Alter’s ancestors

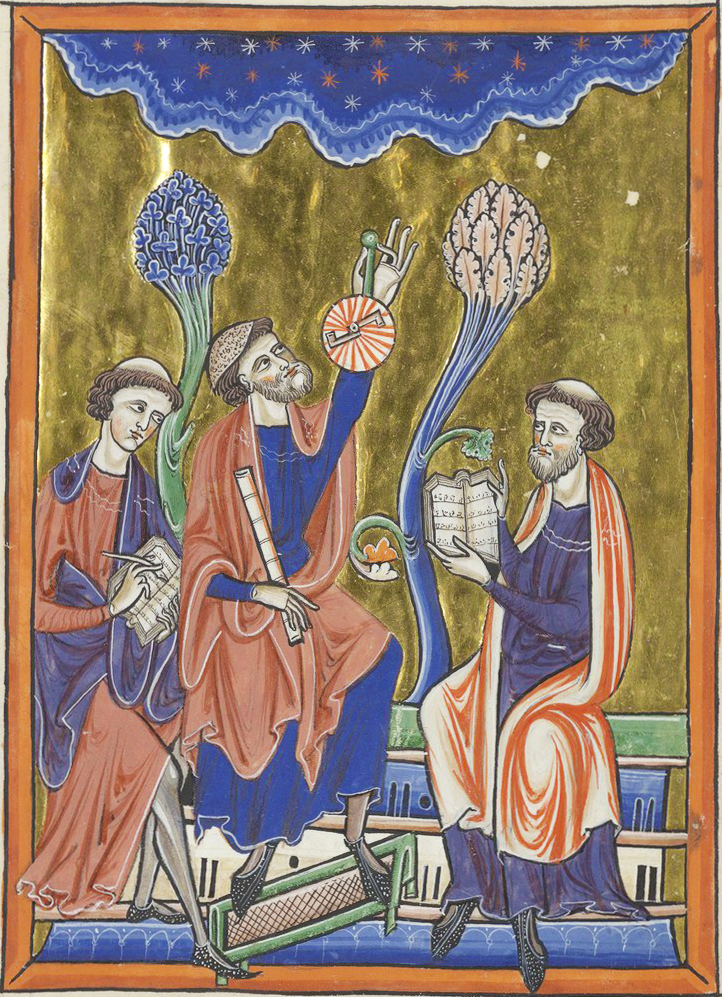

I used the word “rediscovered” regarding the literary qualities that Alter and his peers found in the Hebrew Bible because they were not the first. Medieval and Renaissance commentators also addressed the Bible’s literary features, albeit according to the aesthetics of their own day. Long before the rise of scientific biblical criticism during the 18th and 19th centuries, “pre-modern” scholars studied the Bible from literary and poetic perspectives, developing essential tools that we use to this day. Exceptional contributions that come to mind include Moses Ibn Ezra (b. Granada around 1070), who in his Kitab al-Muḥaḍarah wal-Mudhakarah [The Book of Conversations and Recollections], a treatise on Arabic and biblical rhetoric and poetry, written in Granada during the second half of the 11th century, discusses biblical metaphor, parallel-typed expressions and alliterations. Some 700 years later, Oxford Professor of Poetry, Bishop Robert Lowth (1710-1787), in his Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews (1815), was the first Western scholar to chart out biblical parallelism. He classified the balancing expression of two or more phrases in the poetic sentence as synonymous, antithetic and synthetic, categories which serve in biblical study to this very day.[2]

Even during the 19th and first half of the 20th century, when text-historical and philological approaches prevailed in biblical criticism, there were major breakthroughs in the literary understanding of the Hebrew Bible, as in the works of Erich Auerbach (1892-1957) and Martin Buber (1878-1965).[3]

Alter’s important works on biblical narrative and poetry clearly and openly relate to these and others of his modern predecessors, yet he seems to have regarded such works as beyond the scope of his present new book, perhaps because it sprang, first and foremost, out of his work as an English Bible translator:

Although the impetus of this book was definitely an attempt to consider the challenges of translating the Bible and how they might be met, the topics discussed ended up involving both proposals about literary translation and a general overview of the principal features of style in the Bible. As I have noticed, no such study really exists, and that in itself is a symptom of the problem that these chapters seek to address.

(pp. xv-xvi)

It would perhaps have been informative to relate to these “ancestors” somewhat more. Even in works where style and poetics were not the main concern, literary insights abound. Stylistic observations are scattered through the pages of Midrash, the works of the Church Fathers, and “systematic” Christian and Jewish Bible exegesis through the centuries. Bible translation, a constant and fundamental feature of biblical learning among Christians and Jews, has also heightened awareness of the Bible’s literary style.

What’s new?

Yet Alter is correct that never in its long history of interpretation has the Bible been studied so intensively as “first and foremost” a work of literature. The turn to literature ushered in many new subfields of biblical studies: Bible and gender, Bible and sociolinguistics, Bible and environmental, cultural and trauma studies, and more. Nowadays, these subfields depend on reading strategies that are applied to texts we see as the product of a conscious effort to express ideas through words. Since the 1980s, it has been difficult for readers trained in the academy to read the Bible, whether in its Hebrew original or in translation, without putting on our literary spectacles. Our eyes have been opened to the Hebrew Bible’s literary formation and stylistics, even when we engage in non-literary forms of biblical analysis, such as historical, theological, archeological, comparative-linguistic, and comparative-religious. For some the Bible is only literature, for others it is foremost history, and for yet others it is a Divine message, but most of us engage with it at some level as a literary creation.

“It’s only words” – Translating a sanctified text

The strength of this elegant book lies in Alter’s ability to draw attention to what the biblical authors did – and were capable of doing – with words. He takes pleasure in showing how they had their supremely gifted (or if you like, inspired) way with words as writers, a way of putting them together side-by-side to elicit the optimal emotional and cognitive response. Alter writes on this most complex topic in a direct and personal way, so that any reader, versed or unversed in biblical literature, can take delight in his sensitive and at times exasperating search for English translation equivalents of biblical Hebrew. He illustrates his dilemmas with fine examples.

Take these double word-plays from Zephaniah 2:4:

כִי עַזָה עַזוּבָה תִהְיֶה וְאַשְקְלוֹן לִשְמָמָה אַשְדוֹד בַצָהָרַיִם יְגַֿרְשוּהָ וְעֶקְרוֹן תֵעָקֵר

In Alter’s view they “altogether resist transference into English”, as he finely explains:

The literal sense of the line is “For Gaza shall be abandoned/ and Ashkelon a desolation.// Ashdod at noon shall be banished/ and Ekron be uprooted”. The dire fate of these Philistine cities is clear enough in the English, but what is not visible is how this prophecy is reinforced through the fusion of words. The Hebrew for “Gaza shall be abandoned” is ‘azah ‘azuvah and for “Ekron be uprooted” is ‘eqron te’aqer. The effect is to intimate an indissoluble link between the name of each of the Philistine cities and the verb indicating destruction that immediately follows it, as though the doom of the city were somehow inscribed in its name. It is hard to imagine how this could possibly be conveyed in English.

(p. 77)

What the ancient Hebrew authors did with words so effectively steals our hearts, that their creation is justly considered one of the greatest achievements of world literature. I am not referring to the Hebrew Bible’s enduring impact, sometimes for better and alas, sometimes for worse, in so many areas of religion, law, politics, the environment, gender, and so forth, of Jewish, Near Eastern, Western and World history. Rather, I am referring to the Bible’s art. Alter puts this elegantly in his “Autobiographical Prelude”, when describing how he was lured by his publisher into translating Genesis, and then other biblical narratives, until he succumbed, over two decades, to translating the entire Hebrew Bible into English:

From the beginning my translation was impelled by a deep conviction that the literary style of the Bible in both the prose narratives and the poetry is not some sort of aesthetic embellishment of the “message” of Scripture but the vital medium through which the biblical vision of God, human nature, history, politics, society and moral value is conveyed.

(p. xiii)

Since biblical words have exerted so much power over so many readers through so many generations, the task of translating them into other languages, especially those that, unlike Aramaic, Syriac, and Arabic, do not have a common Semitic structure with Hebrew, is certainly a daunting one, at which many have tried a hand and few have succeeded. Here I will suffice with one fascinating example from the Arabic translation tradition of the Jews. The Karaite Yefet ben Eli and the Rabbanite Saadiah Gaon left us Judeo-Arabic commentaries on this very verse (Zephaniah 2:4), which as highlighted in Alter’s quote above “altogether resists transference into English”.

Yefet ben Eli (Jerusalem, 2nd half of the 10th century) translates the verse into Judeo-Arabic as follows:

.אן ג׳זה תציר מתרוכה ועסקלאן תציר וחשה ואשדוד יטרדוהא פי אלוקת אלט׳הר ועאקר תנעקר

Gazah taṣir matrukah, wa-asklan taṣir waḥshah, wa-ashdod yutriduha fi al-waqt al-ẓuhr, wa-akir tunakir [“Gaza will become abandoned/ and Ashkelon will become desolate// Ashdod will be banished at noon time/ and Ekron will be uprooted“].

Though Yefet somewhat compromises the semantic sense of the last Hebrew phrase of this verse (in bold) in the Arabic target language, he still prefers to use the rare Arabic cognate root (‘qr) in rendering the Hebrew root (‘qr), in order to demonstrate the alliteration to his readers. In his Judeo-Arabic commentary, which follows the translation, he prefers to clarify the semantic and stylistic aspects, such as the gradation in the descriptions of the Nations in the verse:

After (the Prophet) ceased prophesying about Israel he began to prophesy about the Nations. In this chapter he prophesied about many of the nations, starting from those closest (geographically, to Israel). He first mentioned the Land of the Philistines, then Moab and Ammon […] when he said “Gaza will become abandoned” he meant that its people will leave it and move away from it… when he said “Ekron will be uprooted” he meant no memory will be left of its people, and even their footprints will be erased from the place.

While Yefet’s Arabic version tries to capture the alliteration of the last phrase through an existing cognate Arabic equivalent, his commentary draws attention, as a complementary expansion on the translation, to other stylistic aspects. Thus we learn the deeper meaning of the formulation ‘eqron te’aqer in this particularly emphatic structuring of biblical Hebrew syntax, namely, that the city will be utterly erased (including any memory of the fact that people ever walked its paths).

Saadiah Gaon, Yefet’s older Rabbanite contemporary (Egypt and Iraq, 882-942) is also known to have translated and commented upon the Twelve Minor Prophets, yet this work has not come down to us. Nonetheless, we find him explaining the stylistic aspects of this verse in a comment found in one of his last books (Sefer Ha-Galuy, page 168, lines 8-19), as follows:

He (the Prophet) changes the names of Gazah, Ashkelon, Ashdod and Ekron for the worse, similarly to their names, when he says “azah azuvah…we-ekron teaker“. Indeed the changes in the names of Gazah and Ekron are clear enough. Yet we have to explain the similarity in the case of Ashkelon and Ashdod. We suggest this becomes clear when dividing each of these city names into two parts: Ashkelon – means esh (fire) kalon (shame). These will happen – (fire and shame) – when the city will be destroyed, which is why the Prophet said “will become desolate“. Ashdod, when divided, will be ba-esh (in fire) yidod (run away), in fire it will escape, which is why he said “will be banished at noon.” These afflictions are (encoded) in the secrets of the Hebrew language.

Similarly to Alter, Saadiah too recognized that the verse is deliberately structured “as though the doom of the city were somehow inscribed in its name,” and explained his understanding in stylistic terms. Yefet, who also recognized this feature, drew attention in his translation to other stylistic elements in this verse. They both did so in Arabic, a language and culture which put immense stress on questions of correct style (Arabic: faṣaḥah), and so heightened the Jewish exegetes’ awareness of these aspects of biblical Hebrew, to which they also referred as fasiḥ in their Arabic works, while in Hebrew they called it ṣaḥut (elegance, clarity). Thus Abraham Ibn Ezra (born 1089/1092, Tudela, Spain) repeats this idea in his Hebrew commentary on Zephaniah (written in the first half of the 12th century), explaining that the biblical language is expressed here poetically (derekh leshon ṣaḥut). Another great medieval Hebrew commentator, David Kimhi (1160–1235, Narbonne, Provence), also points out the text contains alliteration “lashon nofel al lashon“. Neither of these men of letters elaborated further, however, on the style, perhaps because they knew their audience was less sensitized to it than a typical Arabic-reading audience.

Making choices

Alter’s aim in his compact book is clearly focused and well-achieved. He seeks to explain and illustrate basic choices he made as a translator, in order to highlight and even distill the biblical authors’ Hebrew style. His task is a two-fold literary endeavor. On the one hand, he means to heighten the English reader’s engagement with his own methods of translating the Bible as literature, so that

through the translation (they) would be able to enjoy more keenly the literary achievement of the Bible…

(p. xv)

On the other hand, by explaining his word choices in English, and showing how and why they differ from those of other English translations, Alter tackles principal aspects of biblical style in a direct and uncomplicated manner:

I will explore here how not only word play but also diction, rhythm, syntax and the strategic choice of words (in biblical dialogue) are decisive elements in shaping the literary authority and conveying the moral and religious outlook of the Hebrew Bible…

(p. xiv)

In six illuminating chapters (framed by an Autobiographical Prelude and Suggested Readings), altogether around 130 pages in small print, he does just this. With the light and accurate hand of a master in his art, Alter sketches out translation issues of the kind that trouble all translators of literature to some extent, and Bible translators in particular. They include a personal foray in chapter 1, which he provocatively names “The Eclipse of Bible Translation,” into the history of English Bible translation, especially in relation to the King James Version. The five chapters that follow are strewn with wonderful examples of translation challenges in which the literary aspects of the Hebrew Bible are most pertinent: syntax, word choice, sound play and word play, rhythm and the language of dialogue. Alter reveals his own deliberations, made over the two decades he spent completing his English version of the Hebrew Bible, and later in the commentary, he wrote, as was the practice of the medieval exegetes, to explain the underlying literary reasoning behind his lexical choices.

Bi-lingual translations

Alter’s harking back to the Hebrew source text reminds us that biblical translation has a unique history, often gravitating towards a “bi-lingual” contextualization of the art of translation. English as a target language is perhaps the furthest removed from this tendency, and one should ask why this is so. Yet thinking back on the Hebrew Bible’s translation history, whether into Greek (Septuagint), Syriac (Peshitta), Jewish Aramaic (Onkelos, Jonathan), these were produced for the most part by Jewish translators who strove for self-contained versions in their target languages, while they knew that their translations were not meant (at least in their first stages) to fully replace the Hebrew original. They were meant, in ritual or study, to be performed and read side by side with it. Later on, when Christians adopted some of these versions, or when Jews considered their languages obsolete, they gradually drifted away from their live bi-lingual context. Eastern Christians too held onto their revered translations, even when they stopped speaking Greek or Aramaic. So too when the Arab conquests spread throughout the eighth and ninth century Near East, and Jews and Christians adopted Arabic as their lingua franca, Arabic versions of the Jewish and Christian scriptures functioned alongside the revered text traditions.

Translation between interpretation and explanation

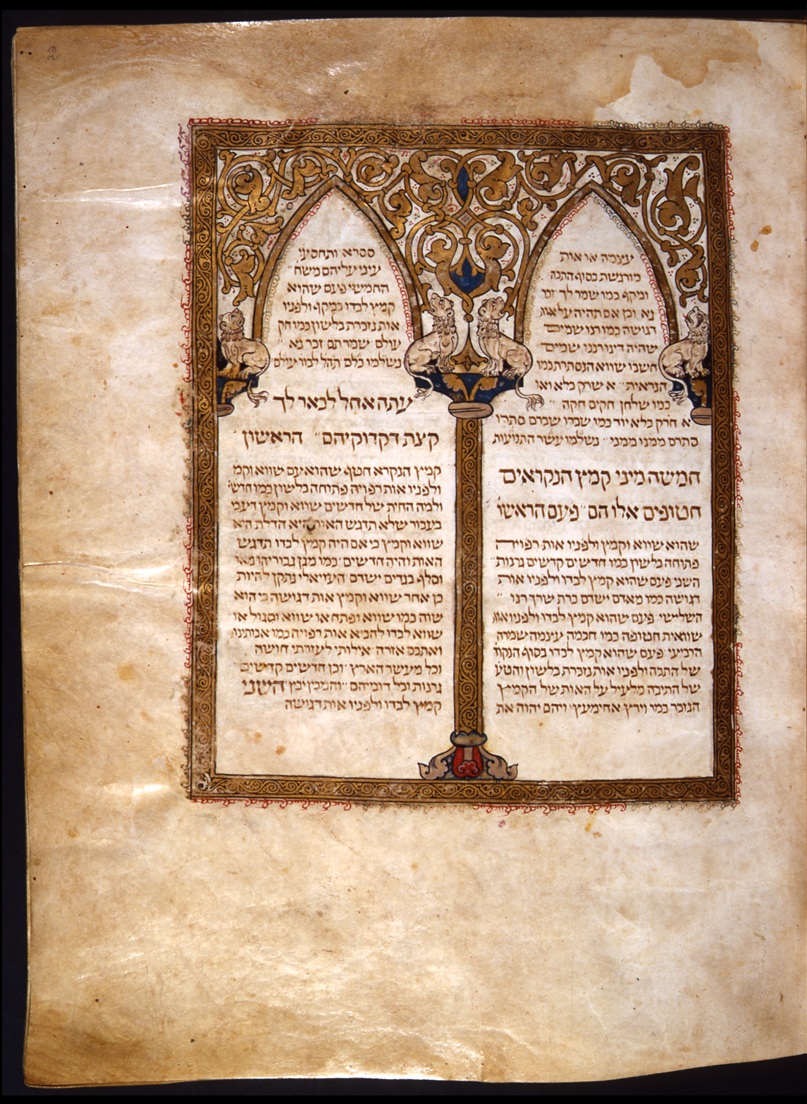

In the Preface to his Arabic translation of the Five Books, known as the Tafsīr, the well-known medieval Jewish translator and commentator, Saadiah Gaon (882-942) refers to the dialogue between the translator and the given text. He reports that he was requested by some readers to compile a short/simple tafsīr on the Five Books (Arabic: tafsīr basīṭ naṣṣ al-tawrah) after he had already written a long/detailed tafsīr (Arabic: tafsīr al-tawrah al-kabīr). The Arabic root fasara, similarly to the Hebrew/Aramiac root pashar denotes both translation and explanation thus mirroring the complexity of any attempt at translation, especially of a revered text, as one involving a detailed explanatory process of the source text.

Scholars consider the purpose of Saadiah’s “short” work was to serve as a succinct interpretive-translation of the Five Books, whereas his “long” work functioned more as a systematic commentary, which may have also included the same or another Arabic translation. It was the “short” self-contained work, however, which circulated separately from his commentary, and gained the status of an almost “standard” Judeo-Arabic version of the Torah. In some Yemenite manuscripts (and modern) prints, Saadiah’s Tafsīr is copied out as the third column or layer, alongside Targum Onkelos (the second layer) and the Hebrew Masoretic text, emphasizing their trilateral mutual dependence and respective authority.

An exchange with John Updike over the need for notations to translation, suggests that Robert Alter sides with Saadiah’s “long tafsīr” format in Jewish translation and interpretation tradition:

I found it rather amusing, a few years later, when John Updike, in a New Yorker review of my Five Books of Moses, wondered, rather querulously, why anybody needed the commentary, which made the book ponderously heavy to hold, since the King James Bible, after all, had done quite nicely without a commentary

(p. xi)

Indeed, Alter goes on to confess how medieval Hebrew commentaries were an inspiration to him in this respect:

I discovered that there were all sorts of things going on in the Hebrew, many having to do with its literary shaping, that had not been discussed in the conventional commentaries and that I wanted to take up. I thus found myself launched on still another unintended enterprise, a commentary to accompany my translation. I have to say that this gave me a certain sense of connection with the great medieval Hebrew commentators – especially my two favorites, Rashi and Abraham ibn Ezra – whom I have admired since late adolescence

(p. xi)

The “classical” medieval Hebrew commentaries printed in the Rabbinic Bible (Mikraot Gedolot), from the early 16th century (paralleling the King James Version), did not include Bible translations, and excluded all commentators who wrote in languages other than Hebrew. This meant that Saadiah Gaon’s works, which pioneered the Arabic model of a verse by verse cohesive Jewish Bible commentary (similar to systematic Qur’anic as well as Christian commentaries and unlike midrashic compilations), were excluded. The same lot befell other Rabbanite and Karaite Judeo-Arabic translations and commentaries on the Bible, which were prevalent in manuscript throughout the 10th -15th centuries in the Near East, North Africa and southern Spain. Indeed, in Andalusia, where Abraham Ibn Ezra was active until the age of 50, Arabic was the lingua franca, and he was well versed in the commentaries of his predecessors. In fact, when moving to Christian European regions in the latter half of the 12th century, Ibn Ezra distilled much of his Judeo-Arabic heritage and learning into Hebrew, sometimes mentioning his sources, at other times disguising them.[4] Perhaps he understood that Hebrew would be his gateway to posterity, or perhaps with an audience unversed in Arabic, he had no choice but to revert to Hebrew as an exegetical language. In doing so he surrendered the layer of “translation”, that layer which was the “sandwich filling” between the slice of Hebrew scripture and the slice of exegesis, and served regularly to Judeo-Arabic readers till then, enabling them to read the biblical Hebrew with the regular insight of translation, as a set structure. It was indeed the Arabic translation, which kept the whole structure in place. The Jews of Christian zones, however, had no literary language into which they could translate until the Renaissance ushered in the European-language translations of the Bible, first among the Christians. Rashi (Troyes, Champagne, 1040-1105) embedded Judeo-French glosses in his Bible commentaries, which are an indication that Jews rendered their scripture in Christian Europe too, orally, though not systematically. Rashi’s work was also affected by exegetical models that reached him from the East, possibly via Byzantium. His Hebrew is clear and crisp, highly communicative when compared to Abraham Ibn Ezra’s rather telegram-like formulations. Both these giants (Ashkenazi and Sephardi) synthesized traditions that came before them. In the age of print, it became a feature of Torah learning to study them alongside the Hebrew Bible (and the Aramaic Targum). In as much as written Bible versions are concerned the Jews in Western Europe came to them rather late, mainly in the age of Enlightenment. A famous example is Moses Mendelssohn’s German version of the Pentateuch (1783), written in High German, and with the intention of enabling Jews to learn this language properly and quickly.[5] Interestingly, this work was called the Bi’ur (in Hebrew: explanation), in a similar sense to Tafsīr, and it also contained a commentary.[6]

Is it possible that Robert Alter would have found dialogue even more rewarding with the Jewish translators and commentators who preceded Rashi and Abraham Ibn Ezra? Men of letters such as Saadiah Gaon, the Karaites al-Qirqisani[7] and Yefet ben Eli, or the Andalusian Moses Ibn Ezra — precisely because they wrote on the Bible in a language other than Hebrew, namely, standard literary Arabic, whose lexical and syntactic affinities with Hebrew enabled them to recognize the beauty and intricacies of the Bible’s literary style?

Meira Polliack is Professor of Bible and the Joseph and Ceil Mazer Chair in Jewish Culture in Muslim Lands and Cairo Geniza Studies at Tel Aviv University. She was one of the Principal Investigators of the DFG funded international research project (2012-2017): Biblia Arabica – The Bible in Arabic among Jews, Christians and Muslims. She has published extensively on medieval Judeo-Arabic Bible translation and biblical exegesis among the Jews of the Islamic world; modern and medieval literary approaches to the Hebrew Bible; historical development of biblical hermeneutics and notions of biblical narrative.

Suggested Citation: Meira Polliack, “Don’t Alter a Word: Thoughts on Robert Alter’s “The Art of Bible Translation” (Princeton University Press: Princeton & Oxford, 2019) in the Wider Context of Hebrew Bible Translation”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 23 February 2021, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121825/.

Footnotes[1] Bee Gees – Words (words and lyrics). For a 1997 live performance see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hGyrNChk5c. The ballad was written in 1968, yet it was in the group’s 1980’s come-back that the song became famous. I am grateful to my dear friend and colleague, Dr. Diana Lipton, for her insightful comments on this essay and her invaluable advice in making it accessible to a wider readership.

[2] For further reading see http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7989-ibn-ezra-moses-ben-jacob-ha-sallah-abu-harun-musa; https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kitab-al-muhadarah-wa-al-mudhakarah; https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Lowth; Adele Berlin, The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1985). Biblical Poetry Through Medieval Jewish Eyes (Indiana studies in biblical literature (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, 1991).

[3] Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature (originally published in German in 1946; Ed. Trans. Willard Trask. Princeton, Princeton University Press 2003) is considered Auerbach’s masterwork, in which he discussed important aspects of biblical (realistic) style. See Robert Doran, “Literary History and the Sublime in Erich Auerbach´s Mimesis” (New Literary History 38.2 (2007): 353–369). On Martin Buber’s deep sense of biblical stylistics, which also permeated his and Franz Rosenzweig’s German translation of the Bible (First Volume published in Berlin, 1925), see Lawrence Rosenwald, “On the Reception of Buber and Rosenzweig’s Bible” (Prooftexts 14 (1994): 141-165). In his Hebrew work, Darko shel mikra, ‘iyyunim be-defusay signon ba-tanakh (Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 1964) [=The Way of Scripture: Studies in Stylistic Patterns of the Bible], Buber coined and discussed the Hebrew term “mila manḥa” [pp/284-299] a ‘guideword’, ‘ leitwort’, ‘leading word’. Buber (and Rosenzweig) considered specific words which appear repeatedly (even if in various declensions) in the biblical text as a stylistic tool meant to guide the reader to the overall meaning of the text/story. See Yairah Amit, “The Multi-Purpose “Leading Word” and the Problems of its Usage” Translated by Jeffrey M. Green (Prooftexts 9 (1989): 99-114).

[4] For a general survey of Abraham ibn Ezra’s works and further references, see Shlomo Sela and Gad Freudenthal, “Abraham Ibn Ezra’s Scholarly Writings: A Chronological Listing” (Aleph 6 (6) (2006)): 13–55. doi:10.1353/ale.2006.0006. ISSN 1565-1525. JSTOR 40385893.

[5] Further on Mendelssohn’s enterprise see Paul Spalding, “Toward a Modern Torah: Moses Mendelssohn’s Use of a Banned Bible” (Modern Judaism, Vol. 19, No. 1 (1999)): 67-82 (Published by: Oxford University Press) URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1396592. Werner Weinberg, “Moses Mendelssohns Übersetzungen Und Kommentare Der Bibel” (Zeitschrift Für Religions- Und Geistesgeschichte, 41, (2) (1989)): 97–118. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23893756.

[6] Similarly to Saadiah who only managed to add a long commentary to the books of Genesis and part of Exodus (the rest undertaken by his students), only the commentary on Exodus was written by Mendelssohn himself. Many of the German Jews in that period spoke Yiddish and were literate in Hebrew. The commentary was also thoroughly rabbinic, quoting mainly from medieval exegetes but also from Talmud-era midrashim.

[7] The Karaite al-Qirqisani (Iraq, early 10th century) actually wrote a treatise on Bible translation in Arabic, known as al-qawl ala al-tajamah, which has not survived, though he does address translation issues in his other works.

Leave a Reply