by Ronny Vollandt

The research project “Biblia Arabica: The Bible in Arabic among Jews, Christians and Muslims,” was originally conceived by researchers from Freie Universität Berlin (Sabine Schmidtke) and Tel Aviv University (Camilla Adang and Meira Polliack) and won a DFG DIP grant (“Deutsch-Israelische Projektkooperation”) in 2012. It is the very first project in the humanities ever to receive this prestigious grant. In 2015 the German side of the project moved to Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich (LMU), after Sabine Schmidtke was appointed to the Institute of Advanced Study, Princeton, and I joined the LMU around the same time, having previously been a post-doc on the project. Since then I have co-directed the German side of Biblia Arabica with Andreas Kaplony.

From the outset, the objectives of the project were simple: to close scholarly lacunae and provide an infrastructure for a dynamic and fast-developing field.

The lacunae were countless. Biblical scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries traditionally shunned Arabic translations of the Bible for what they perceived to be a lack of value for textual criticism. In their view, primacy was given to age, and texts were put into stemmata, in the search for an elusive Urtext. In neither aspect did Arabic translations do particularly well. Not only were they too young compared to Greek or Syriac versions, but most Arabic versions were in fact of a tertiary rank, being translated translations as it were. What is more, for this previous scholarship Arabic versions belonged to a “rival realm,” namely the realm of Islam. Attainments in the fields of philosophy or the natural sciences might have found suitable expression in Arabic, the literary koine of Islamic hegemony. Yet the idea that Late Antique scriptural heritage stemming from Hebrew, Syriac, Greek, Coptic or Latin could strive for or achieve an unprecedented moment of originality under this hegemony and in Arabic would have disrupted the almost arbitrary preconceptions of the time—preconceptions which imagined that the Jewish, Christian and Samaritan communities now under new rulers were experiencing, at best, a state of intellectual stagnation or, at worst, a complete tabula rasa.

Biblia Arabica has employed about 15 doctoral and post-doctoral students over the last six years, with topics ranging from biblical narratives in the Quran, to the Judaeo-Arabic translation of and commentary on the Book of Job by Yefet b. Eli, to manuscripts of the Pauline Epistles in Arabic. We have held several international conferences on the Arabic Bible in Tel Aviv, Berlin, Uppsala and Cordoba. SBL and EABS now have panels dedicated to this topic. Most of the results of the project will be published (or have already been published) in the recently established book series Biblia Arabica: Texts and Studies, published by Brill in Leiden and edited by an international team of six scholars, including Camilla Adang, Meira Polliack, Sabine Schmidtke and myself. What is more, Biblia Arabica has teamed up with a number of cutting-edge projects from related fields.

Together with the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, we have created a collected, bilingual volume on biblical translations in the Near East that is accompanied by an online exhibition. From this volume, we took the idea even further and curated an exhibition on biblical manuscripts and biblical traditions in the Near East at the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin.

At least some scholarly lacunae have been closed through these initiatives, but in the process, we discovered many new ones. As to scholarly standards, we attempted to set these by providing infrastructure to the field. An online and searchable bibliography tool, which will be the subject of the next blog, was developed by the Biblia Arabica team in Munich to serve as the most comprehensive guide to date for research in the growing field of Arabic Bible. The additional descriptions and tags for each entry provide valuable guidance for each subtopic, and the digital format makes it easy to browse the entries and use them in further research.

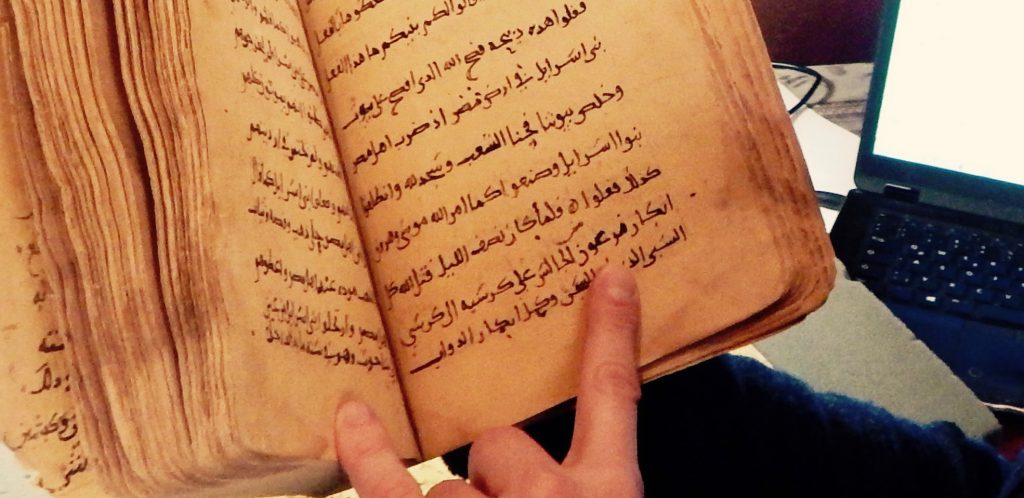

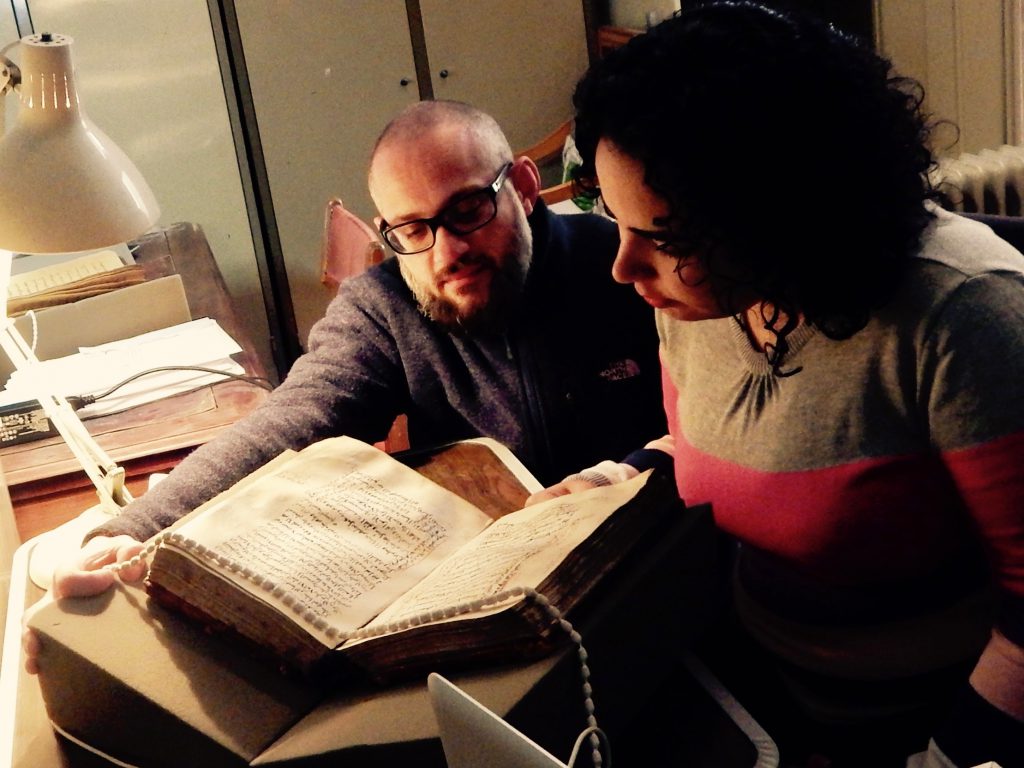

Over the course of the project, the most pressing need we’ve found is for a way to locate manuscripts containing Arabic Bible translations. Each of us has compiled our own lists representing the subset of manuscripts relevant to our research, out of the ten thousand that are estimated worldwide. It has sometimes taken hours or days to find basic information about a single biblical manuscript. In the most elusive cases, it has required a visit to the archive or library where the manuscript is held. It could be—and should be—easier to answer questions such as, “Where can I find Arabic translations of the book of Isaiah?” or “Which is the earliest dated copy of the book of Exodus in Arabic?” Moreover, Arabic Bible manuscripts represent a rich heritage, but one that is largely invisible to the non-specialist, documenting the history of the Arabic book and the lives of sundry Middle Eastern communities.

In the next years, we envision addressing this need through a subject-oriented union catalogue of Arabic Bible manuscripts. Current print catalogues, which usually describe the manuscripts from a single archive, are extremely uneven in their coverage, and Graf’s indispensable Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur is outdated. More and more archives are digitizing their manuscript collections and placing them online, which makes it possible to find and read a manuscript if you know its shelfmark. But these seldom offer a scholarly description of the manuscript, and it is not possible to search several digital inventories at once. A union catalogue would be the first stop for those interested in Arabic Bible manuscripts, directing them to digitized collections where available, as well as to further literature. It would also provide a place for scholars of the Arabic Bible to add the kinds of codicological and paleographical details that are often missing from catalogues. Already Biblia Arabica team members have been discussing with collaborators such as EMEL and ParaTexBib some aspects of how to undertake such a massive cataloguing effort.

This brings me to the future of Biblia Arabica. With the end of the year, the initial funding by the DFG will end. From then on, Biblia Arabica will cease to be a project and will become a larger consortium for scholars interested in the Arabic Bible. It will continue as an international platform for research in the field, providing an infrastructure and an umbrella for independent research projects.

Ronny Vollandt is Professor for Judaic Studies at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich and co-directs the Biblia Arabica project.

Suggested Citation: Ronny Vollandt, “Biblia Arabica becomes a consortium: Looking back on six years of research”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 23 October 2018, DOI: 10.5282/ubm/epub.107515.

Leave a Reply