by Martino Diez

* This post is a shorter version of the following book chapter: Diez, M., The Translation of the Psalms by Mohammad al-Sadeq Hussein and Serge de Beaurecueil, in John C. Cavadini and Donald Wallenfang (ed.), Evangelization as Interreligious Dialogue, Pickwick Publications, Eugene (OR), 2019, pp. 163-186.

In 1961 the Cairo publishing house Dār as-Salām issued an Arabic translation of the Psalms by a Muslim intellectual, Mohammad al-Sadeq Hussein, with the participation of the French Dominican Serge de Beaurecueil. This instance of Islamic-Christian biblical teamwork, in which also the future Archbishop of Algiers, Henri Teissier, was partly involved, is rather extraordinary in its kind, as is the cultural atmosphere in which the project was first conceived. What is more, the translation, which was basically produced from the French version of the Psalter contained in the Bible de Jérusalem, obtained the imprimatur of the Vicar Apostolic of Alexandria of the Latins. In spite of its quite exceptional status, this work, to my knowledge, has not been the object of any specific study.[1]

The roots of the project

The 1961 translation was born at the crossroads of a Muslim interest in Western culture and spiritual matters from the side of al-Sadeq Hussein and a desire for a more ‘inculturated’ liturgy from the side of Serge de Beaurecueil.

Although not much is known about al-Sadeq Hussein, the scant biographical notes we possess (essentially a brief passage introducing the first sample of fifteen Psalms published in MIDEO in 1957) suffice to suggest that he – as well as his more illustrious brother Kamel Hussein, the author of the acclaimed novel Qarya Ẓālima (‘City of Wrong’) – belonged to the milieu of cultivated professionals and state officials who played a key role in what Albert Hourani has famously defined as the liberal age of the Arabic thought. Although many of these Egyptian liberals were unsatisfied with the strictures of traditional ulama, they were often imbued with a religious quest, which led some of them to look with new eyes at Christianity, beyond the traditional controversies and polemics of the past.

On the other hand, Serge de Beaurecueil (1917-2005) is among the founders of the IDEO, the Dominican Institute for Oriental Studies in Cairo, which played a crucial role in the renewal of the Catholic approach to Islam. Having arrived in Cairo in 1946, de Beaurecueil devoted himself to the study of the Hanbali Sufi master ʿAbd Allāh Anṣārī from Herat (1006–1089). In due course, this choice would lead him to Afghanistan, where he would spend 20 years (1963-1983) giving shelter to around 60 children in his home in Kabul, before being repatriated in the wake of the Soviet invasion of the country.

In his 17 years in Egypt, de Beaurecueil was also active serving youth and quickly became aware of the necessity of an autochthonous Arabic liturgy, as opposed to the attempts at his time to create a Westernized French-speaking Egyptian élite. He therefore was allowed by Rome to adopt the Coptic rite, but already in an article dating to 1953 he deplored the poor linguistic quality of its texts, calling for “a correct, simple, transparent, comprehensible language, placing within everybody’s reach the richness of liturgy and the Biblical texts from which it draws inspiration”.[2] It is probably here that the project of the Psalter translation first took shape.

An additional motive was that de Beaurecueil wished to bring to the Arabic readers the fruits of the great renewal that was occurring in biblical studies, as the adoption of the Bible de Jérusalem as its source text reveals. This choice, at any rate, was accompanied, for the first 15 Psalms, by “a constant reference to the Hebrew text”[3] thanks to the young Henri Teissier, an intern at the time at the IDEO. After the first specimen of 15 Psalms was published in 1957, however, Teissier was compelled to leave Cairo and interrupt his collaboration. The team may have continued to refer from time to time to the Hebrew original – de Beaurecueil had probably received some instruction in Hebrew in his novitiate – but the bulk of the work was certainly done on the French version.

Finally, it is worth stressing that, while de Beaurecueil may have wished to downplay his own role in the initiative, there is no reason to doubt that the actual paternity of the translation goes to al-Sadeq Hussein. The division of tasks is indeed clearly outlined in the introduction to the 1961 edition.[4]

A Qur’anic Flavor

As we have just seen, de Beaurecueil had expressed his wish for a liturgy in correct Arabic already in 1953. But the participation of a Muslim translator, and the personal maturation of de Beaurecueil through his studies of Sufism, led him to a new step. While in 1953 he had warned about the risks inherent in the use of Qur’anic Arabic, he now openly declared:

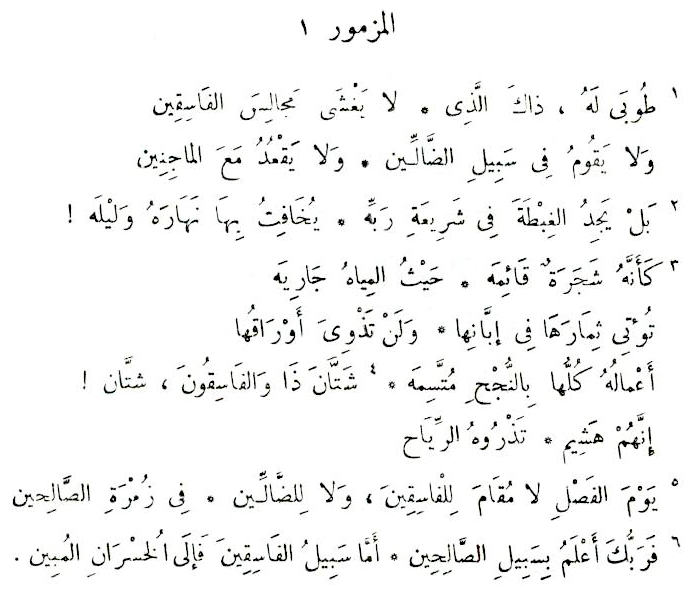

Far from avoiding the expressions that are current in the Islamic religious language, we have not hesitated to adopt them whenever they corresponded exactly to the original sense of the text, without however ‘Islamizing’ it.[5]

De Beaurecueil gives only a few examples of the lexical choices he made with al-Sadeq Hussein, but they are of great import.[6] One example will suffice. A thorny issue in translating biblical passages into Arabic is how to express the notion of divine goodness. Many Christian Arabs resort to the term ṣāliḥ, but in the Qur’anic vision this word cannot be predicated of God as it only applies to the believer who accomplishes the ‘good deeds’, aṣ-ṣāliḥāt. In its place al-Sadeq Hussein and de Beaurecueil propose the word karīm, ‘generous, noble’. Their translation also avoids employing Rabb (‘Lord’) in the absolute state, preceded by the article (ar-Rabb), because in the Qur’an the term always occurs in the construct state.

Of course, whenever Arabic and Hebrew share a word, the translators, at least while working with Henri Teissier, tried to preserve the lexical kinship. But in fact – I quote the testimony of Mgr. Teissier – “the evolution of words in the two languages made it difficult to employ the Hebrew root to choose the Arabic word”.[7] Therefore, rather than insisting on forcing the target language to imitate its source, it is on the stylistic level that al-Sadeq Hussein’s version strove to echo the original Hebrew text. The most relevant feature in this translation is indeed the use of saǧʿ (‘rhymed prose’) whenever possible. The hallmark of Qur’anic style, this stylistic device is perfectly adaptable to parallelism, the formal organizing principle of most Psalms and more generally of the so-called ‘Semitic rhetoric’.

And yet, this option does not force the text into the Islamic mold. As its title makes clear, the Sifr al-Mazāmīr is indeed a Christian translation, faithful to the original and even meant for liturgical use, although it is moved by the persuasion that the Psalter, properly rendered, can strike some chords in the Muslim soul.[8] At any rate, the existence of an Arabic translation of the Psalms done by a Muslim and bearing an ecclesial imprimatur is certainly not a minor fact. It is worth clearing away the cobwebs and reexamining it—and, perhaps, putting it to use again in Islamic-Christian encounters.

Martino Diez (https://www.oasiscenter.eu/en/martino-diez, https://unicatt.academia.edu/MartinoDiez) is Assistant Professor of Arabic Language and Literature at the Catholic University of Milan and scientific director of the Oasis International Foundation.

Suggested Citation: Martino Diez, “The ‘Qur’anic’ Translation of the Psalms by Mohammad al-Sadeq Hussein and Serge de Beaurecueil”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 20 November 2018, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121666/.

[1] The main facts about the translation are accurately laid out in Avon, Les Frères prêcheurs en Orient. Les dominicains du Caire, 757–758. Some references can be found also in Pérennès, Passion Kaboul, 74, 124.

[2] De Beaurecueil, “Un problème crucial : la langue liturgique”, 11.

[3] Al-Sadeq Hussein, “Quinze psaumes traduits en arabe”, 2.

[4] “Muhammad al-Sadeq Hussein set to work with a profound knowledge of the Arabic language and its styles and a deep concern for the religious and poetic values of the Book of Psalms. My participation [here de Beaurecueil is speaking in the first person] was meant first and foremost to meticulously revise with him the translation so as to be sure of its details and its accuracy” (Al-Sadeq Hussein, Sifr al-Mazāmīr, 18). To this explicit statement one may add the fact that al-Sadeq Hussein is always referred to as the translator throughout the MIDEO articles, and in MIDEO 6 (“Les psaumes 26 à 50”) allusion is made to “some Christian readers who have raised some concerns because of the fact that the translator is a Muslim” (p. 2). It is true, however, that the same article speaks of a “tight collaboration” (p. 2) between the Egyptian intellectual and the French Dominican.

[5] Al-Sadeq Hussein, “Les psaumes 26 à 50”, 2.

[6] Al-Sadeq Hussein, “Quinze psaumes”, 1–2.

[7] Personal communication to the author, April 8, 2018.

[8] This conviction was shared also by the famous Lebanese convert Afif Osseïrane (1919-1988), who prepared another ‘Qur’anic’ version of the Psalter just one year before al-Sadeq Hussein and de Beaurecueil. Some samples of his translation are available on the blog http://psalmsosseiran.blogspot.it/

RAZA

This is brilliant translation. I loved the way he uses rhymes. Super Excellent.