by Miriam L. Hjälm

1. Among the rich manuscript treasures kept at the British Library, we find more than one hundred Christian Arabic Bible translations and Bible commentaries. [1]This work was part of a research project sponsored mainly by the Swedish Research Council (2017–01630), which I conducted together with Camilla Adang and Meira Polliack. The last part was made … Continue reading So far, information about them has been dispersed in a dozen manuscript catalogues. This dispersion of information has made it rather difficult—even for experts in the field—to navigate through the corpus and locate relevant material. As a means to increase accessibility to these valuable objects, I have for several years had the pleasure to re-examine these manuscripts, select some for digitization, write a few blogs on them (here and here), and finally gather all the data into a new catalogue. [2]The catalogue, A Catalogue of Christian Arabic Bible Translations at the British Library, will appear in the series Studia Byzantina Upsaliensia 23; Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Blogs … Continue reading

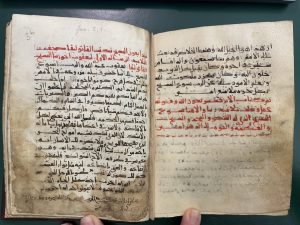

2. The main purposes were to collect all the shelfmarks into one and the same volume, standardize and add codicological and content-related information, and provide indices for scribes, calendars, acquisition notes etc. In addition, the new catalogue includes sample illustrations of the manuscripts so that readers interested in a specific scribe, place, or time period, can easily get an idea of the basic material features of a specific codex. Lastly, it includes a couple of hitherto un-catalogued manuscripts, which so far only have been referenced in Peter Stock’s and Colin F. Baker’s Guide or in the handwritten acquisition register at the library. [3]Colin F. Baker and Peter Stocks, Subject Guide to the Arabic Manuscripts in the British Library (London: The British Library, 2001). In this post, I want to take a closer look at some of my favourite finds and also talk about the challenges of cataloguing them.

Favorite Finds

3. The most exciting part of the work was perhaps to order up uncatalogued sources. Among these, we find Or. 16059 (fig. 1), a Syriac-Arabic interlinear psalter produced in the 14th century, which was included as item 43 in K.W. Hiersemann’s Katalog 500 (1922). [4]For this manuscript, see also Peter Tarras, “Tracing a Lost Sinaitic Manuscript through a Bible Quotation,” Biblia Arabica Blog (31 May 2023), URL = … Continue reading The copy lacks any immediate source of acquisition but the date 3 November 2004 followed by the initials “V.N.” is penned down at the end of the codex. The initials probably stand for Vrej Nersessian, who was the curator of the Christian Middle East Section at the library at that time. [5]Many thanks to Michael Erdman for helping me identify the name. The note also informs us that the manuscript used to be part of Arnold Mettler’s (1867–1945) collection and that Mettler deposited the manuscript in Zurich’s university library, where it had the reference Zurich Or. 95. As Peter Tarras has shown, it was later sold to the American collector Otto Orren Fisher (1881–1961). [6]See Peter Tarras, “The Legacy of a Failed Amateur Enthusiast: Friedrich Grote’s Sinaitic Manuscript ‘Discoveries’ and Their Post-Sinaitic Fate,” forthcoming. Many thanks to the author … Continue reading Tarras convincingly argues that the manuscript may originally have been taken from Saint Cathrine’s Monastery to Europe by the German collector Friedrich Grote (1861–1922) and that a missing folio of the manuscript is now extant in Vatican, BAV, Vat. Sir. 647, folio 168. [7]See ibid.

4. Another favourite find of mine was Or. 8605 (fig. 2), a parchment manuscript, which transmits a very early version of Acts and the Catholic Epistles in Arabic. Georg Graf mentioned the manuscript in 1925 and one year later, Fritz Krenkow offered a longer description of it. [8]Georg Graf, “Sinaitische Bibelfragmente,” Oriens Christianus 12–14 (1925): 217–220; and Fritz Krenkow, “Two Ancient Fragments of An Arabic Translation of the New Testament,” The Journal … Continue reading In 2006 , Paul Géhin noted that a part of this manuscript is extant in Paris, BnF, Ar. 6725 (Acts 9:15–12:13), and that it had been separated from the London copy already when Graf had access to the manuscript. At that time, it was still in the possession of Grote. [9]Paul Géhin, “Manuscrits sinaïtiques dispersés I: Les fragments syriaques et arabes de Paris,” Oriens Christianus 90 (2006): 23–43, here 29. On Grote, see also Peter Tarras, “From Sinai to … Continue reading More recently, Tarras has discussed the manuscript’s acquisition history. [10]Ibid. Other than this, it has not received much attention and certainly not as much as the other two early specimens at the library: Add. 26116, brought to the library by the famous Constantin Tischendorf (1815–1874) on 11 July 1865, and Or. 8612 acquired in 1920 from Friedrich Wilhelm Bickel who was in fact Grote’s brother-in-law (which means that the manuscript comes from the Grote Collection as well). [11]Ibid., 78, 86. On Add. 26116, see for example Wolf W. von Baudissin (ed.), Translationis antiquae arabicae libri Jobi quae supersunt nunc primum edita (Leipzig: Doerffling & Franke, 1870) and … Continue reading

☛ Short Facts About the 105 Manuscripts

Calendars in Colophons:

– Coptic Era of the Martyrs: 34 % (36 manuscripts) use this calendar (of these, 12 use it in parallel with the Hijra Calendar)

– Hijra Calendar: 17 % (18 manuscripts) use this calendar (of these, only 3 use this calendar alone)

– Byzantine World Era: 6,7 % (7 manuscripts) use this calendar (of these, 3 use it in parallel with the Hijra Calendar)

– Seleucid Era: 5,7 % (6 manuscripts)

– Julian/Gregorian Calendar: 3 % (3 manuscripts)

In total: 52 % (55 manuscripts) of the corpus is dated

Languages and Scripts:

– Arabic and Coptic: 40 % (42 manuscripts)

– Karshuni (Arabic in Syriac letters): 5,7 % (6 manuscripts)

– Syriac and Arabic: 3,8 % (4 manuscripts)

– Syriac and Karshuni: 1 % (1 manuscript)

– Latin and Arabic: 1 % (1 manuscript)

– Ethiopic, Syriac, Coptic, Arabic (Karshuni), and Armenian: 1 % (1 manuscript)

– Arabic, Greek, and Latin: 1 % (1 manuscript)

– Arabic and Greek: 1 % (1 manuscript)

In total: 54 % (57 manuscripts) are bilingual or more

Biblical Books:

The two most frequently copied books are Psalms (22 manuscripts) and the Gospel of John (22 manuscripts). Among the Psalms, 12 (55%) contain Psalm 151 and 8 (36%) represent Ibn al-Faḍl’s revision.

5. The handwriting—an Early Abbasid bookhand—seems to be identical to Sinai Ar. NF Parch. 15 and its continuation Sinai Ar. NF Parch. 64 and Sinai Ar. NF Parch. 36, that is, manuscripts from the ninth–tenth centuries produced at the Monasteries of Mar Chariton or Mar Saba in Palestine. [12]Géhin, “Manuscrits sinaïtiques,” 30; Miriam L. Hjälm, “A Paleographical Study of Early Christian Arabic Manuscripts,” Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 17 (2020): 37–77, at 60–61. The parchment codex is made up of 58 folios, which are arranged so that the so-called hair side, i.e., the folio page of an usually brighter tone, is facing another hair side. This layout conforms to a premodern rule of high-quality book production. A page measures ca. 170 mm x 125 mm, with the text block measuring 125 –130 mm x 100 mm. The text has 18–19 lines per page. The codex is regularly made up of quaternions, i.e., booklets (so-called “quires”) of four bifolios. Each new quire is marked with Greek numbers in the upper left corner of the recto. Like Or. 8612, the library acquired Or. 8605 from Bickel in 1920. [13]However, the acquisition dates differ slightly from one another: Or. 8612 was acquired on 10 April 1920, while Or. 8605 was acquired on 5 December 1920. The significance of this find lies in its representation of the early stage of Christian Arabic Bible production and as a sample of the hitherto poorly studied reception of Acts and the Catholic epistles in Arabic.

6. In the handwritten acquisition register, we also find Or. 11334 (fig. 3), seemingly copied between the 17th–19th centuries, which contains Ibn al-Faḍl’s revision of Psalms and the Ten Biblical Odes. The copy is written on Western paper, made up of 157 folios, where a page measures ca. 170 mm × 110–120 mm (text block: ca. 120–130 mm × 70 mm). Catchwords are marked on the lower margin at the left corner of a verso. As is common in the Rūm Orthodox tradition, the psalms are divided into 20 kathismata, doxai, and into saḥar. In addition, a prayer is included after each kathisma. The codex was bequeathed to the library by a R.S. Greenshields on 10 October 1931.

Some Challenges

7. The cataloguing process was not without challenges: First, what is a biblical book to the respective communities? An example is the History of the Jews, which is seldom understood as canonical yet included in the “full bible” in Or. 1326 and thus seemingly seen as authoritative by the scribe of that manuscript. I therefore also included Or. 1336, which consists of this book only. Second, it is a challenge to collect relevant manuscripts at the library, especially since bilingual Arabic texts can be included in just any catalogue on texts in the second language or they can be unclearly referenced in handwritten records. Thirdly, it is difficult to date undated manuscripts based only on palaeography. Yet in the catalogue, manuscripts are arranged according to date and a provisional date therefore had to be given to all of them based on codicological data such as writing support, quire marks, and/or catch numbers. In addition, it is sometimes hard to identify Greek-Coptic abbreviations or Syriac and Karshuni (Arabic in Syriac script) numbering systems. Finally, figuring out the correspondence between ancient book titles and modern ones (esp. the Maccabees), finding proper terminology, keeping up consistency in the descriptions all add to the challenge of cataloguing. I hope, however, that my catalogue will enable more people to access and take interest in the many important finds kept at the library, which in turn will enrich our understanding of the Bible in Arabic, its history, and the communities that produced them.

Miriam L. Hjälm is a lecturer in Eastern Christian Studies at Sankt Ignatios College, University College Stockholm, and a researcher at the Department of Linguistics and Philology at Uppsala University in the project Retracing Connections: Byzantine Storyworlds in Greek, Arabic, Georgian, and Old Slavonic (c. 950 – c. 1100). Her primary research interests include the reception of the Bible and patristic exegesis in Arabic, the re-writing of biblical material in hagiographies, reception theory, inter-religious encounters among Jews, Chrisitians, and Muslims, as well as material philology. Her publications include Christian Arabic Versions of Daniel (Brill, 2016) and, co-edited with Marzena Zawanowska, Strangers in the Land: Travelling Texts, Imagined Others, and Captured Souls (Brill, 2024).

Suggested Citation: Miriam L. Hjälm, “A New Catalogue of Christian Arabic Bible Translations at the British Library”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 20 November 2024, URL: https://biblia-arabica.com/a-new-catalogue-of-christian-arabic-bible-translations-at-the-british-library/. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

References

| ↑1 | This work was part of a research project sponsored mainly by the Swedish Research Council (2017–01630), which I conducted together with Camilla Adang and Meira Polliack. The last part was made within a project sponsored by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (M19-0430:1) in Byzantine Studies led by Ingela Nilson. In addition to these three people, I also wish to thank the curators at the British Library, Colin Baker and later Michael Erdman, for their help with this project. Finally, I wish to express my gratitude to Peter Tarras for discussing the pre-published version of the blog post with me. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The catalogue, A Catalogue of Christian Arabic Bible Translations at the British Library, will appear in the series Studia Byzantina Upsaliensia 23; Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Blogs include those linked in the text above: Miriam L. Hjälm, “Christian Arabic Bible Translations in the British Library Collections,” Asian and African Studies Blog (23 November 2020), URL = https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2020/11/christian-arabic-bible-translations-in-the-british-library-collections.html; and eadem, “Christian Bibles in Muslim Robes with Jewish Glosses: Arundel Or.15 and other Medieval Coptic Arabic Bible Translations at the British Library,” Asian and African Studies Blog (10 April 2022), URL = https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2022/04/christian-bibles-in-muslim-robes-with-jewish-glosses-arundel-or15-and-other-medieval-coptic-arabic-b.html?. |

| ↑3 | Colin F. Baker and Peter Stocks, Subject Guide to the Arabic Manuscripts in the British Library (London: The British Library, 2001). |

| ↑4 | For this manuscript, see also Peter Tarras, “Tracing a Lost Sinaitic Manuscript through a Bible Quotation,” Biblia Arabica Blog (31 May 2023), URL = https://biblia-arabica.com/tracing-a-lost-sinaitic-manuscript-through-a-bible-quotation/. |

| ↑5 | Many thanks to Michael Erdman for helping me identify the name. |

| ↑6 | See Peter Tarras, “The Legacy of a Failed Amateur Enthusiast: Friedrich Grote’s Sinaitic Manuscript ‘Discoveries’ and Their Post-Sinaitic Fate,” forthcoming. Many thanks to the author for sharing it before publication. |

| ↑7 | See ibid. |

| ↑8 | Georg Graf, “Sinaitische Bibelfragmente,” Oriens Christianus 12–14 (1925): 217–220; and Fritz Krenkow, “Two Ancient Fragments of An Arabic Translation of the New Testament,” The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 2 (1926): 275–285. |

| ↑9 | Paul Géhin, “Manuscrits sinaïtiques dispersés I: Les fragments syriaques et arabes de Paris,” Oriens Christianus 90 (2006): 23–43, here 29. On Grote, see also Peter Tarras, “From Sinai to Munich: Tracing the History of a Fragment from the Grote Collection,” COMSt Bulletin 6/1 (2020): 73–90. |

| ↑10 | Ibid. |

| ↑11 | Ibid., 78, 86. On Add. 26116, see for example Wolf W. von Baudissin (ed.), Translationis antiquae arabicae libri Jobi quae supersunt nunc primum edita (Leipzig: Doerffling & Franke, 1870) and Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, Libro de Job en versión árabe (Códice Árabe Sinaítico 1, S. IX) (Madrid: Editorial Sindéresis, 2022). For Or. 8612, see Vevian Zaki, The Pauline Epistles in Arabic: Manuscripts, Versions, and Transmissions, Biblia Arabica, 8 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2021). |

| ↑12 | Géhin, “Manuscrits sinaïtiques,” 30; Miriam L. Hjälm, “A Paleographical Study of Early Christian Arabic Manuscripts,” Collectanea Christiana Orientalia 17 (2020): 37–77, at 60–61. |

| ↑13 | However, the acquisition dates differ slightly from one another: Or. 8612 was acquired on 10 April 1920, while Or. 8605 was acquired on 5 December 1920. |

Leave a Reply