by Peter Tarras

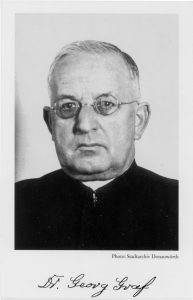

1. Anyone who works on Arabic translations of the Bible, especially Christian translations, knows the name Georg Graf (1875–1955) very well. With the first volume of his Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, he has created a reference work that is still indispensable today. [1]Georg Graf, Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, vol. 1: Die Übersetzungen, Testi e studi, 118 (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1944). See also Ronny Vollandt, Arabic … Continue reading Graf’s method of differentiating Arabic Bible translations into versions and recensions and organising the manuscript tradition accordingly is likewise still guiding current research. However, Christian Arabic translations of the Bible were only one of Graf’s many fields of activity. He was a pioneering researcher for the history of this subject and many others in Eastern Christianity, not to mention his strong interest in the local history of his native region Swabia. [2]See Samir K. Samir, “Georg Graf (1875-1955), sa bibliographie et son rôle dans le renouveau des études arabes chrétiennes”, Oriens Christianus, 84 (2000), pp. 77-100; Hubert Kaufhold, … Continue reading The remainder of his Nachlass, the collection of documents he left behind, has now been transferred to the Bavarian State Library in Munich, making it possible to study this personality and his scholarly work in depth.

2. Already six years ago, I published a short note about Georg Graf’s Nachlass on this blog. At the time, it was divided into two parts. Now at the beginning of June this year, both parts were reunited after more than 60 years. The Bavarian State Library now holds Graf’s entire Nachlass. The State Library had owned part of it already for several decades. It was probably purchased for the State Library by Hermann Bojer (1913-1988) who headed its Oriental department until 1988. The much larger part of the Nachlass had been in the possession of Prof Hubert Kaufhold since 2001. He now handed it over to Dr Maximilian Schreiber, head of the Autograph and Personal Collection Department of the State Library (fig. 2). Schreiber was particularly delighted that Kaufhold has already made a detailed inventory of the part he was taking care of. This part also contains what is left of Graf’s correspondence, which needs to be inspected again separately. The entire Nachlass is now listed under the call number Ana 831.

3. After Graf’s death in 1955, scholars occasionally paid visits to his sisters in Dillingen, where he had lived with them. Prof Kaufhold assumes that Bojer bought the first part from them. Julius Aßfalg (1919-2001) must also have been one of these visitors. Aßfalg was a long-time protégée of Graf and later Professor of Eastern Christian Studies (or “Philologie des christlichen Orients”) in Munich. He kept the larger part of the Nachlass for around half a century. Kaufhold told Schreiber and me that it was more of a chance find. He had asked his teacher Aßfalg whether he had any of Graf’s material. Aßfalg must have simply forgotten about it over time. Kaufhold then rediscovered the twenty boxes (fig. 3) under a table in Aßfalg’s home after his death and was more than surprised when he realised what was inside.

4. Imagine having to organise all your notes and bibliographical references in such boxes. The digital age has made this practice obsolete, although it was still used by many scholars only a few decades ago. Graf’s Nachlass also provides a fascinating insight into this practice of scholarly work. Kaufhold used the material himself for some publications and once described it as follows: “Preserved are […] twenty cardboard boxes with drawers, in which he mainly kept notes, excerpts, extracts from publishing catalogues, galley proofs, newspaper cuttings, relevant correspondence etc., arranged by subject (churches, literature and others) and inserted in provisional, labelled cardboard envelopes, mostly old magazine covers. […] The notes are written on all kinds of writing materials, for economic reasons during the war and probably also due to a lack of paper: normal writing paper, blank backs of letters, manuscripts or galley proofs and the like”. [3]Hubert Kaufhold, “Einleitung”, in: Georg Graf, Christlicher Orient und schwäbische Heimat: Kleine Schriften, vol. 1, ed. by Hubert Kaufhold, Beiruter Texte und Studien, 107a (Würzburg: Ergon … Continue reading

5. Graf’s Nachlass not only allows us to study how the scholar worked and organised the material for his projects. It also contains some potential treasures for research. These include numerous copies of manuscripts, some of which Graf must have obtained from other scholars abroad. For example, there is a whole collection of material on the oldest Arabic translations of the Bible, including a letter written in German by the Russian Arabist Ignaty Kračkovsky (1883-1951), dated 3 June 1929. Graf also owned several copies of Sinaitic manuscripts (including the Bible manuscripts Sin. ar. 75 and 155). His knowledge of the manuscripts of St Catherine’s Monastery was therefore more extensive than we have previously assumed. We also come across two original copies of Garshuni manuscripts from St Mark’s Monastery in Jerusalem, which Graf had made by the monk Yuḥannā Garūm on site. [4]One of the manuscripts was exhibited in Dillingen in 2005 as part of an exhibition in Graf’s honour. See H. Kaufhold, Katalog der Ausstellung im Rathaus Dillingen, p. 20-21. They contain legends of saints. In the first part of the Nachlass I found fragments of three manuscripts of Egyptian origin whose description I will soon publish: [5]Peter Tarras, “Neue Fragmente koptischer Herkunft aus dem Nachlass Georg Grafs”, in preparation. a fragment of a Life of St Macarius of Alexandria (d. 395), a longer fragment of a commentary on the Book of Revelation, and a Coptic-Arabic liturgical manuscript. These fragments were separated from the Nachlass and now bear the following shelfmarks: Cod.arab. 2897, Cod.arab. 2898, and Cod.copt. 36. In a limited sense, Graf thus also appears to us as a manuscript collector. But it is very clear that his interest was primarily scholarly.

6. In my first post on Graf’s Nachlass, I expressed the hope that this material would one day be available in digital form. For the original manuscripts that we find in it, this could indeed be the case in the near future. The rest, however, is difficult or even impossible to digitise due to its heterogeneous composition and the fact that individual parts obviously form certain units that cannot be traced digitally. So anyone who wants to work with the material will inevitably have to come to Munich to insepct it on site. I very much hope that it will be of interest to specialists, especially those who work on the history of Orientalism in Germany. Graf has not yet been sufficiently studied in this context. I also hope that I have been able to document the condition and recent history of the Nachlass in a helpful way with my posts.

Peter Tarras studied Philosophy, Islamic Studies, and Near and Middle Eastern Studies in Kiel, Munich and Sheffield. His doctoral research was focused on the 10th-century CE Muslim philosopher al-Fārābī and his notion of evil. Peter is a research assistant in the ERC project MAJLIS: The Transformation of Jewish Literature in Arabic in the Islamicate World. Previously, he has worked for the Arabic and Latin Glossary (Julius-Maximilians-Universität, Würzburg). His areas of interest include intellectual history in the Near and Middle East, book history, manuscript studies, provenance research, and science communication. Since 2023, he is running the blog and resource site Membra Dispersa Sinaitica which is dedicated to the dislocated manuscripts of St Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai, Egypt.

Suggested Citation: Peter Tarras, “Reuinted After Over 60 Years: A Further Note on Georg Graf’s Nachlass”, Biblia Arabica Blog, 3 July 2024, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.121838. License: CC BY-NC.

References

| ↑1 | Georg Graf, Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, vol. 1: Die Übersetzungen, Testi e studi, 118 (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1944). See also Ronny Vollandt, Arabic Versions of the Pentateuch: A Comparative Study of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Sources, Biblia Arabica, 2 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2015), p. 17. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Samir K. Samir, “Georg Graf (1875-1955), sa bibliographie et son rôle dans le renouveau des études arabes chrétiennes”, Oriens Christianus, 84 (2000), pp. 77-100; Hubert Kaufhold, Christlicher Orient und schwäbische Heimat: Leben und Werk von Prälat Professor Dr. theol. Dr. phil Georg Graf (15. März 1875 – 18. September 1955): Katalog der Ausstellung im Rathaus Dillingen a.d. Donau anläßlich der Gedenkveranstaltungen zum fünfzigsten Todestag Georg Grafs am 17. und 18. September 2005 in Dillingen (Würzburg: Ergon, 2005). |

| ↑3 | Hubert Kaufhold, “Einleitung”, in: Georg Graf, Christlicher Orient und schwäbische Heimat: Kleine Schriften, vol. 1, ed. by Hubert Kaufhold, Beiruter Texte und Studien, 107a (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag, 2005), pp. XV–XXXVI, at pp. XV–XVI; Eng. tr. mine. |

| ↑4 | One of the manuscripts was exhibited in Dillingen in 2005 as part of an exhibition in Graf’s honour. See H. Kaufhold, Katalog der Ausstellung im Rathaus Dillingen, p. 20-21. |

| ↑5 | Peter Tarras, “Neue Fragmente koptischer Herkunft aus dem Nachlass Georg Grafs”, in preparation. |

Leave a Reply